Sexist attitudes affect the credibility of statements on gender (in)equality. However, Isabel Inguanzo, Hugo Marcos-Marné, Araceli Mateos and Homero Gil de Zúñiga argue that the gender and expertise of the source of the message interact with these attitudes. Here, the authors suggest potential improvements to communication strategies in gender equality campaigns

Backlash against measures to improve gender equality is on the rise around the world. As this backlash spreads, more and more citizens are questioning the credibility of public statements about pervasive gender inequalities. But what influences people's willingness to either accept or question statements about gender disparity?

Previous studies on the credibility of politically contested messages have focused on their content and the characteristics of the source. Yet such research has tended to ignore how these elements interact with people's pre-existing beliefs and attitudes. This gap is problematic because psychological research has long since established that individuals are influenced by confirmatory biases when evaluating new information.

We wanted to find out how sexist attitudes, and the characteristics of the person delivering a particular message, affected people's willingness to accept such messages

We ran an experiment in Spain analysing people's assessment of the credibility of statements on gender (in)equalities. Our aim was to discover how sexist attitudes and the characteristics of the person delivering the message interact.

Modern sexism encompasses multiple elements. It includes denial of gender discrimination, rejection of demands for gender equality, and lack of support for gender-positive policies. In a nutshell, contemporary sexists assume that gender equality has already been achieved. Any additional anti-discrimination laws or measures to empower women, these people argue, would grant unfair advantages exclusively to women.

Widespread modern sexism, which seems to be on the rise, has political consequences. We see it in voter turnout, in assessment of political candidates, and in the increasing vote for radical right-wing parties. Our study suggests that modern sexism also filters the way people process and assess the credibility of statements on gender equality.

Empirical evidence gathered so far suggests the speaker's gender may affect how willing people are to believe a message about gender equality. Sometimes, female sources appear more credible. However, people may also see female sources as having a vested interest, and therefore non-neutral.

People generally perceive scientists as neutral, trustworthy sources. Activists they regard as less reliable

Nevertheless, the effects seem clear regarding a source's expertise. People generally perceive scientists as neutral, trustworthy sources. Activists they regard as less reliable. We studied most of the direct effects of these variables on the credibility of statements on gender (in)equality. Despite this, we still hadn't established how these effects interact with prior beliefs and attitudes to foster (or hamper) the credibility of a particular statement.

To remedy this, we designed a vignette experiment embedded in an online survey conducted in Spain, among 2,307 residents over 18 years old. We first asked a set of questions that allowed us to measure levels of modern sexism (and additional controls). Then, we presented a statement – about the gender pay gap – to respondents who had been randomly assigned to five different groups. For each group, the statement was the same, but its source had different characteristics. The statement read: Today in Spain, there is a significant wage gap between men and women. The characteristics of the source varied as follows:

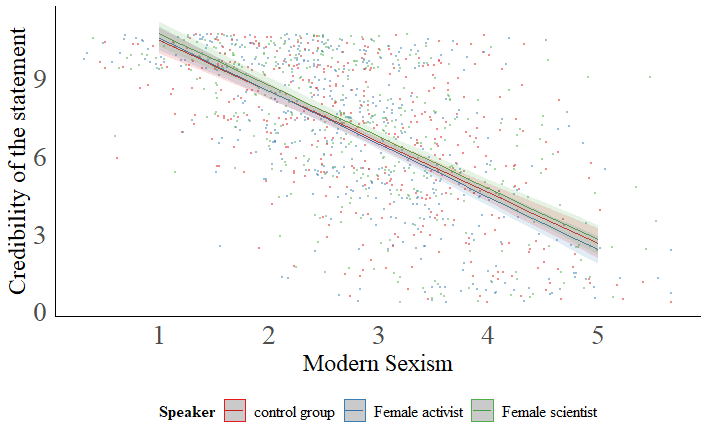

In line with our expectations, findings confirmed that modern sexism is indeed an important predictor of a message's credibility. Less predictably, we also found that female sources (whether activist or scientist) did not make any difference to the credibility of the statement when compared with the control group (no source specified).

Our research confirmed that sexism is indeed an important predictor of a person's inclination to accept a particular message

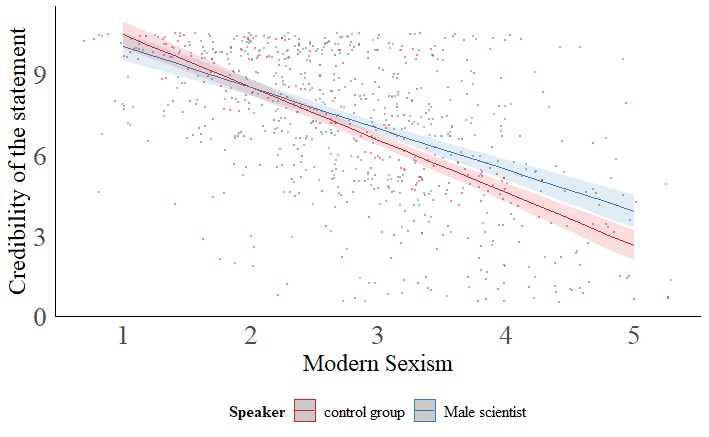

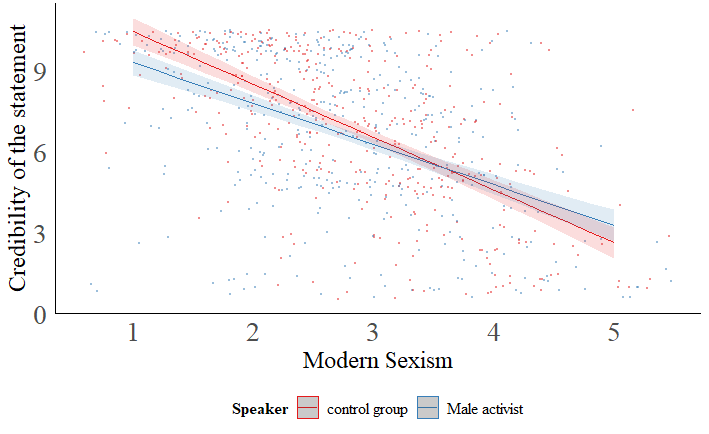

Crucially, the experimental design allowed us to get more fine-grained results about the interactions between variables. For more sexist individuals, the message on gender economic inequality is significantly more credible when it comes from a male scientist. Finally, least sexist individuals find the statement less credible when it comes from a man identified as a feminist activist.

We believe these findings may have important implications for feminist advocates and for institutions involved in awareness-raising campaigns for gender equality. The main takeaway from our research is that it might be worth tailoring these campaigns to fit different audiences. In particular, social movements and public institutions could adjust the spokesperson according to the audience.

In that regard, when addressing predominantly sexist people, audiences would perceive messages on existent gender inequalities as being more credible if they were delivered by a male scientist. Conversely, when addressing a more feminist public, communications managers should avoid using male feminist activists as speakers. When making these important decisions, political actors would be wise to consider the goals of different campaigns and events.