Around the world, the quality of democracy – and citizens' support for it – is in decline. In this context, Seema Shah argues that the future legitimacy of the democratic model depends on the separation of democratic values from democratic procedures

Is the outcome of a free election always 'democratic'? Contemplating this question, Adam Przeworski recently asked, 'Are we defending democracy or the values we ascribe to democracy? And what is the answer to this question when different people attach different values to democracy?'

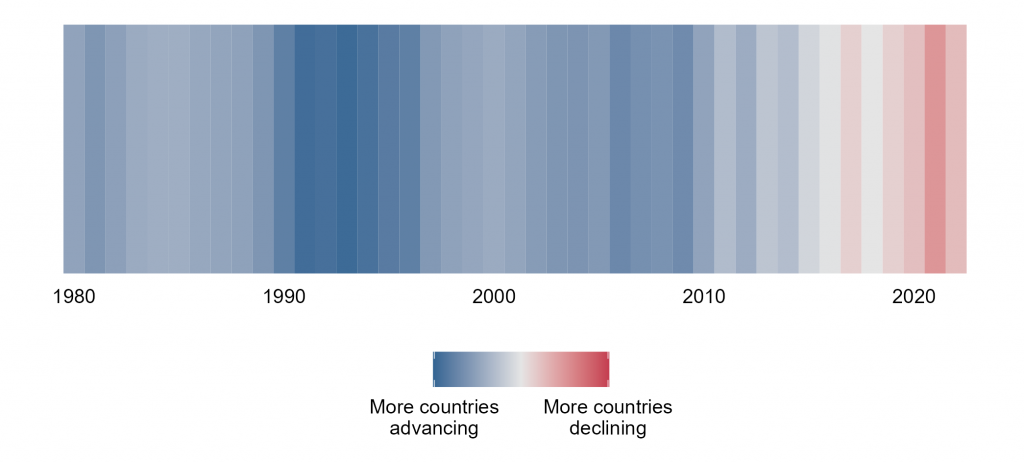

Arguably, it's an especially difficult time in which to answer these questions. International headlines scream about the outbreak of wars. Red flags are raised in the wake of elections that bring to power leaders who promise exclusionary, restrictive and non-collaborative policy reform. The climate disaster, quite literally at times, knocks on our windows. Cost-of-living concerns, meanwhile, sit like empty weights in our pockets. In the face of this reality, it’s difficult not to wholeheartedly defend the values so many of us ascribe to democracy. This is especially true now, as data reveals a sharp drop in the quality of democracy around the world:

One of the problems, of course, is that the list of values we ascribe to democracy can easily end up being little more than a litany of 'all things bright and beautiful'. This strips democracy of the very diversity that brings it to life. Moreover, it makes it easy to selectively dismiss the free choices of voters as 'undemocratic'. To do that, however, is divisive, furthering a longstanding divide between those who adhere to and those who are critical of the dominant liberal democratic model. Indeed, a widening circle of critics even disparages the prioritisation of democracy as 'neocolonial'.

Conflating 'democracy' and democratic values is dangerous for the future legitimacy of the democratic model

Deriding outcomes that are the result of legitimate processes as 'undemocratic' adds fuel to this fire. It makes it appear as though outcomes can only be 'democratic' if certain leaders or people judge them as positive. Perhaps more worryingly, however, conflating 'democracy' and democratic values is dangerous for the future legitimacy of the democratic model.

And this is where Przeworski’s question becomes critical. What, exactly, are we defending? What can we do when varied or even opposing values are associated with democracy? At this point, it is easy to get caught in the ongoing battle between minimalist and maximalist definitions of democracy. Should 'democracy' include social and economic rights, gender equality and independent media? Or should it be limited to credible elections and 'core' rights like the freedom of expression and freedom of association? Delving into this question is unlikely to result in consensus. However, being more deliberate about separating values (which often characterise policies, judgments and choices) and procedures (which technically facilitate people’s control of public decision-making) could be helpful.

There is, of course, some unavoidable overlap. Is an independent media a value or a procedure, for example?

Focusing on the minimum set of tools that is strictly necessary to facilitate and guarantee people’s control over public decision-making may be a useful way to think about what is essential to achieving an outcome that sincerely represents people’s priorities and views. Schumpeterian minimalism did just that. The underlying assumption, however, was that elite leaders, who knew better than majorities, would check ideas or desires that strayed from their own priorities.

Today, increasingly popular options like sortition and citizens’ assemblies are evidence of interest in reducing the divide between leaders and their constituents. They remind us that at the root of democracy is the idea that 'the people' determine the shape of their government and the direction of that government’s policy. What is pivotal is that the rules and institutions which allow people to exercise that control are publicly legitimate and functional. This greatly increases the chances that the results of elections, policy debates, or other processes represent the people’s views.

Ensuring democracy's rules and institutions are publicly legitimate and functional greatly increases the chances that election results genuinely represent the views of the people

Some may call this a 'democratic' outcome. It is important to avoid that characterisation, however, because that makes it sound like contentious or illiberal outcomes are somehow not publicly legitimate. But as Przeworski says, several parties of the 'extreme Right' (often described as anti-democratic) do not necessarily violate the norms of minimalist conceptions of democracy. These parties, having come to power via publicly legitimate and fair electoral processes, are representing the popular will. In that sense, they very much are democratic. What could tip things in the other direction is any wilful act to subvert the democratic mechanisms that brought them to power.

The more useful question to ask in these scenarios is what motivates public support for outcomes that are purposely exclusionary or restrictive. What fears or perceived threats drive such electoral choices? And what can representative political institutions do to mitigate these fears and incentivise buy-in?

Characterising policies we don’t like as 'undemocratic' may dangerously erode broad-based support for the core concept of democracy

After all, key to advancing racial justice, economic equality or climate action, for example, is understanding and addressing the reasons why people don’t support such policies. Also critical is reminding everyone that democracy is for the benefit of all of us precisely so that, at the very least, we ensure broad-based support for the core procedures and concept of democracy. Characterising policies we don’t like as 'undemocratic' may dangerously erode what is left of that very necessary consensus. Scholars have already addressed these questions; the key now is to turn those findings into practical policy action.

What is maybe more important, especially for the legitimacy of the democratic model, is to confront the fact that democratic mechanisms do not guarantee 'bright and beautiful' results. That doesn’t weaken democracy’s legitimacy. It heightens it, demonstrating that everyone has a chance to make their voices (and priorities) heard. That is perhaps the best demonstration that democracy can, and does, deliver.

https://opposition.international/2024/02/26/response-to-seema-shahs-op-ed-in-the-loop-eu/