TikTok deportation propaganda is fast becoming the new border wall. States, platforms and algorithms are fusing into a single machine. This, says Mimi Mihăilescu is turning deportation into bingeable content, burying resistance in the feed, and replacing physical walls with algorithmic control. Local populism dies and global spectacle rules

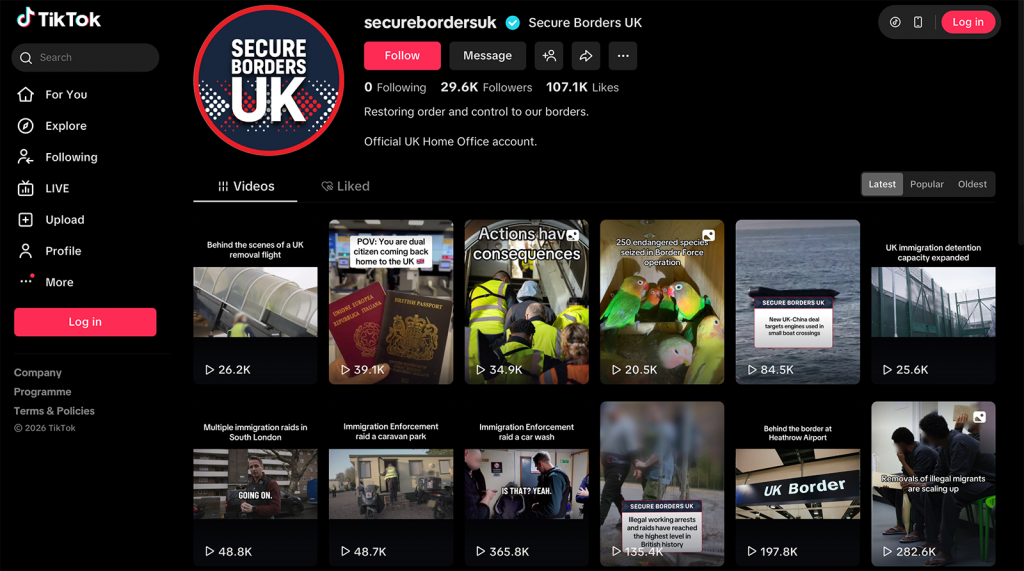

In January 2026, the UK Home Office launched @SecureBordersUK on TikTok. The account typically posts clips of handcuffed migrants being loaded onto deportation flights with slogans about 'restoring order and control'. The clips quickly went viral. UK commentators accused the government of'turning brutality into clickbait' and 'copying Trump'. Supporters praised the account's no‑nonsense aesthetic as proof Labour could be as tough on migration as any right‑wing government.

But this fundamentally mistakes imitation for integration. The UK's adoption of MAGA-style immigration content was not an independent choice. Rather, it was a leap into a globally-coordinated narrative infrastructure that reached full capacity on 22 January 2026, when control of TikTok passed to Trump-allied investors .

The timing reveals coordination. The White House launched its TikTok account in August 2025, crediting the platform with boosting Trump's youth vote. The UK Home Office followed with identical aesthetics: close‑ups of uniformed officers, sped-up action, triumphant text overlays and an implicit promise that they were 'just getting started'.

Migrants appear only as blurred bodies, never as people with stories or rights. The message is not just that the state is in control. It is that migrants' suffering is part of the show. The account reframes deportation as a sharable lifestyle genre. Deporting migrants thus becomes a phenomenon you scroll through and enjoy, rather than a contested policy through a single corporate platform operating on engagement metrics, not democratic accountability.

In the US and UK government's border force TikTok accounts, migrant deportation becomes entertainment for the casual scroller

Traditional right‑wing populism was localised: leaders tailored their rhetoric to domestic audiences; local media ecosystems and institutions constrained their activities. Algorithmic populism collapses these distinctions.

The UK and US governments now mobilise electorates using identical frameworks around identical policies. They synchronise mass deportation as order restoration, and distribute the content at an algorithmic scale. Platforms have replaced parties as infrastructure. The White House, Home Office, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have transformed into content producers. These institutions compete for visibility in feeds that prioritise engagement over accuracy. Here, synthetic politics becomes important: the worry is not just fake content, but that digital infrastructures themselves might begin to simulate political conversation while hiding the structural steering done by platforms and their owners.

The danger becomes visible when we look at what happened to anti‑deportation speech. Within days of TikTok's ownership transition, users reported that videos critical of ICE would not upload. TikTok blamed a power outage but the timing defies credibility: the exact weekend American ownership finalised, the platform systematically failed to distribute anti-ICE content while amplifying pro-deportation government messaging.

Within days of TikTok's ownership transition to Trump-allied investors, videos critical of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement refused to upload

Formally, nothing was off limits. No public rule forbade anti‑ICE content. In practice, however, that content became undeliverable. This is a textbook case of algorithmic censorship: in theory, users are free to post what they want; in practice, much of what they want to say fails to reach its target audience. As long as the company can point to technical issues, responsibility dissolves into systems diagrams and engineering jargon. At the very same time, government‑aligned deportation clips from US and UK actors continued to circulate freely.

The asymmetry is obvious. One side enjoys stable distribution, in‑house production and cross‑promotion with traditional media. The other faces unpredictable technical blocks and an opaque appeals process. Content that appears alive in the feed has in fact been engineered in ways that favour state enforcement narratives, and quietly downgrades those who contest them.

At the same time, immigration control is moving deeper into the infrastructure of platforms. ICE and other agencies have expanded their social media surveillance using commercial tools to scrape profiles, map networks, and feed location and interaction patterns into risk scoring and enforcement workflows. Trivial online traces – a like, a comment – can surface in an immigration file or tip off a raid. Posts critical of the US get flagged. Immigrants' social media activity, including years-old posts, becomes evidence for deportation.

The border is no longer just a geographic line, but has mutated into algorithmic systems. In the UK, the Home Office explicitly markets its TikTok clips as deterrence. Posts communicate 'we will find you' to prospective migrants without the need to build costly walls or detention centres. Combined with targeted advertising, such content can reach people long before they encounter a physical border. The frontier becomes diffuse, stretched across millions of screens everywhere and nowhere, operating continuously, sorting populations by opaque criteria.

The UK Home Office TikTok account communicates 'we will find you' to prospective migrants without the need to build costly walls or detention centres

These trends reconfigure the very definition of 'border'. No longer is a border simply a line on a map or a checkpoint. Now, it could be a composite of ranking systems, content policies, data‑sharing deals and viral aesthetics. If you cross that border, a platform whose logics are set elsewhere may or may not see you. The result is a consolidation of state power.

All these points lead to a simple but unsettling conclusion: what is at stake is far deeper than governments’ unethical use of social media, or the risk of mis/disinformation circulating online. The core functions of democracy, like contesting policy, exposing abuse, and organising resistance, now pass through infrastructures structurally vulnerable to capture by the very actors they are supposed to hold to account.

If deportation becomes just another TikTok genre and anti‑deportation speech is merely a 'technical issue', politics will have deteriorated from a clash of ideologies to merely a managed spectacle.

The cruelty is real, but the argument around it is hollow. Governments and their allies can saturate feeds with glossy enforcement content while they quietly redirect and throttle their critics – or even render them invisible. That is not an accidental side‑effect of a chaotic internet but the shape of a new synthetic border politics. This structural shift demands not simply better fact‑checks or content rules, but structural responses.