Igor Ahedo Gurrutxaga uses a puzzle to achieve organisational change in public institutions. Solving the puzzle seems difficult, because it requires us to think outside the box. Yet the answer can serve as a metaphor for the need to change an organisation’s attitude

How can we foster organisational change? This is a question I face every time I run a new participatory workshop on institutional organisational design. The civil servants and politicians who take part in these workshops always turn up believing that ideas based on standard models won't work.

Broad consensus exists that there is a mismatch between organisational practice and the growing complexity faced by public institutions. This has encouraged me to suggest that public institutions shift from a technocratic mindset to a new relational-deliberative outlook.

In the workshops I run, participants like the idea that, rather than simply considering what organisations already know, institutions must be able to learn. They can do this using networks of knowledge, action and innovation that transcend individual organisations. This commitment to relational-deliberative planning, however, requires a significant change in the attitude of the technocrats and politicians who run those organisations.

Organisations must start by admitting ignorance (to the extent that reality goes beyond specialised knowledge). In this way, they will be able to see alternative perspectives and thus generate different responses.

Only by first admitting ignorance will organisations be able to see alternative perspectives

Doing so requires organisations to look outwards, towards their social environment and other organisations. They must also look inwards, connecting departments or institutional areas.

We must orient this openness towards relationship and interaction, as a condition for learning and incorporating complexity.

Most professionals and political leaders attending my workshops understand the need to reformulate the framework for looking at institutions. Yet they tend to remain in their comfort zone, and appear resistant to change. Above all, the difficulty of making the new organisational horizon visible hampers discussion.

When tackling organisational problems, our brains crave immediate answers that use predictable connections

More importantly, these change-resistant attitudes predetermine the possible solutions. I have learned that we need a metaphor for changing the way public organisations think. I believe that the need to make visible what it means to change the interpretive framework will respond to organisational difficulties and resistance. But not only this. These difficulties and resistance are also based on our very structure of thought, because the human brain craves immediate answers. To do this, our brains use regularities and predictable connections, which are intimately linked with our practices. This is something I want to change.

This need for predictable regularities and connections makes it difficult to solve the puzzle I use for reflecting on institutional organisational change.

I have presented this puzzle to dozens of managers and workers in public organisations as a starting point for reflection. Most have not been able to solve it. This is because our brain makes us see something that does not exist, but that is extremely attractive for a mind that seeks certainties and security: a square.

The difficulty of finding a solution shows how cognitive frameworks determine the way we observe (and act within) reality. The square figure that does not exist is seductive because of its rationality, regularity, and predictability. This is why it emerges in our mind. And this prevents us from finding an answer outside its limits, because it activates paradoxical thinking.

The frustration this exercise causes is a good starting point for demonstrating the difficulty of finding answers to organisational needs using the logic to which we are accustomed. Such logic is permanently present to us, but it no longer fits reality, because reality no longer exists. This exercise helps me show that we no longer know.

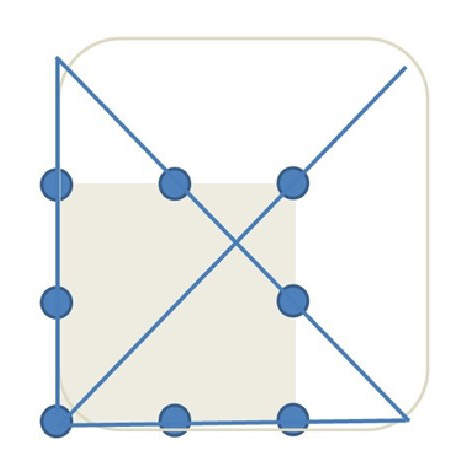

The solution also allows me to direct organisational leaders towards organisations that need to learn from a relational-deliberative point of view. As I say, they think outside the box of specialist knowledge to find different answers through outward and inward relational articulation. If we put these recommendations into practice, the answer to the puzzle becomes clear.

This puzzle helps illustrate four key principles. Firstly, realities that do not exist but that are part of our routine (such as the square; here, representing a world designed for technocratic organisations) do not help us solve real problems, such as the need to adapt our organisations.

To solve organisational problems we must look outside, to society, and to other organisations, before structuring the inside

Secondly, to solve problems and connect organisational structures we must look outside (to society, other organisations) before structuring the inside.

Thirdly, with an open, prejudice-free attitude, if the logic we use is relational (joining all the dots in an innovative way), the sum of the parts may be more than the whole appeared.

Finally, the exercise presents implications which go beyond organisational change. It also feeds into the debate on the necessity of societal change. We are in the midst of an ecological, healthcare, economic and political crisis. To avoid political mistrust, we need to ensure that the people running our political systems are able to learn and evolve.