Using Human Rights Measurement Initiative methodology to evaluate how the United States performs on human rights, Pablo Cesar Santos-Pineda reveals the country has been failing to meet its obligations in relation to education, food, health, housing and work. This failure represents an opportunity for the governing US Democrats

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) is the first global initiative to track countries' human rights performance. It produces scores for up to five Quality of Life rights for around 200 countries. These scores use indicator data supplied by countries to international databases.

HRMI analyses the data using the award-winning Index of Social and Economic Rights Fulfillment (the SERF Index) developed by Susan Randolph, Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer. SERF takes into consideration a country’s financial resources, and generates an income-adjusted score. This score then gauges how close a country is to fulfilling its human rights obligations, compared with other countries with similar resources. The scores are given in percentages, with categories (or bands): ‘very bad’, ‘bad’, ‘fair’, ‘good’.

Generally, a score of 100% on the performance of a right indicates that a country is keeping its human rights promises within its financial constraints. Any score less than 100% highlights a gap in performance – and the country should aim to do better.

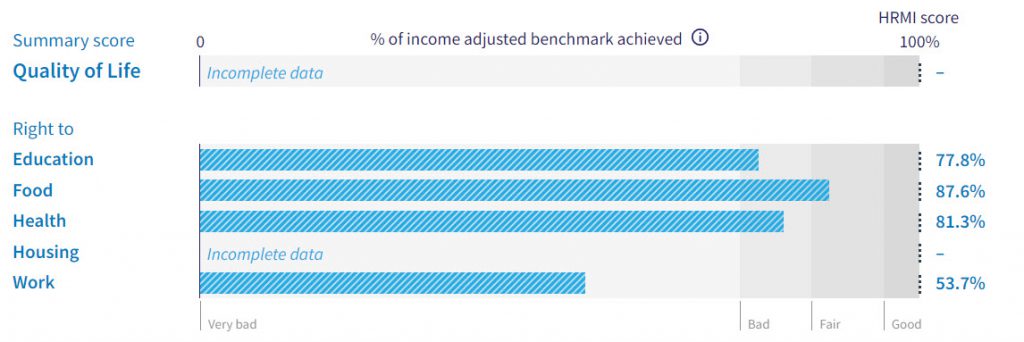

So how well does the US, the world’s second-largest democracy, perform on this index? If we drill down into the different categories, not very well. On the right to education, the US performance, at 77.8%, falls in the ‘bad’ range.

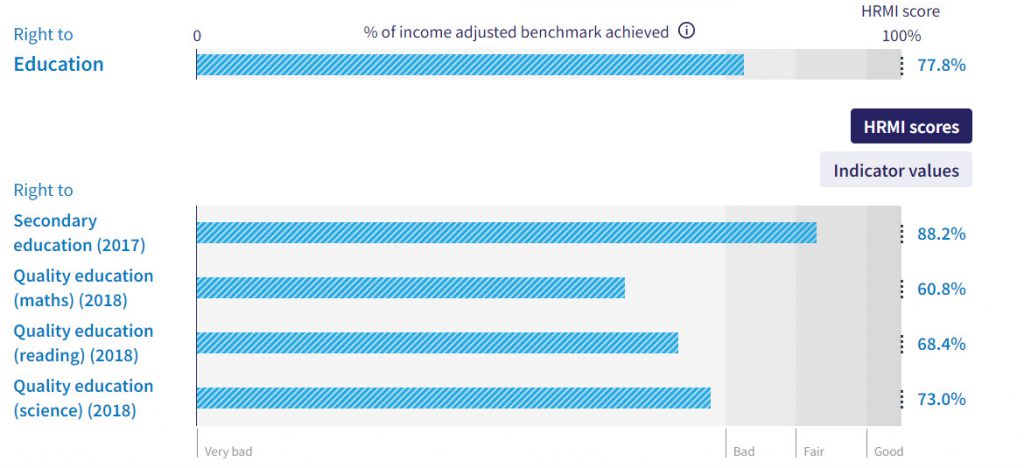

However, if we look at how the right to education is broken down in the following figure, the US does a ‘fair’ job in ensuring children have access to secondary education, but the quality of that education rates ‘very bad’.

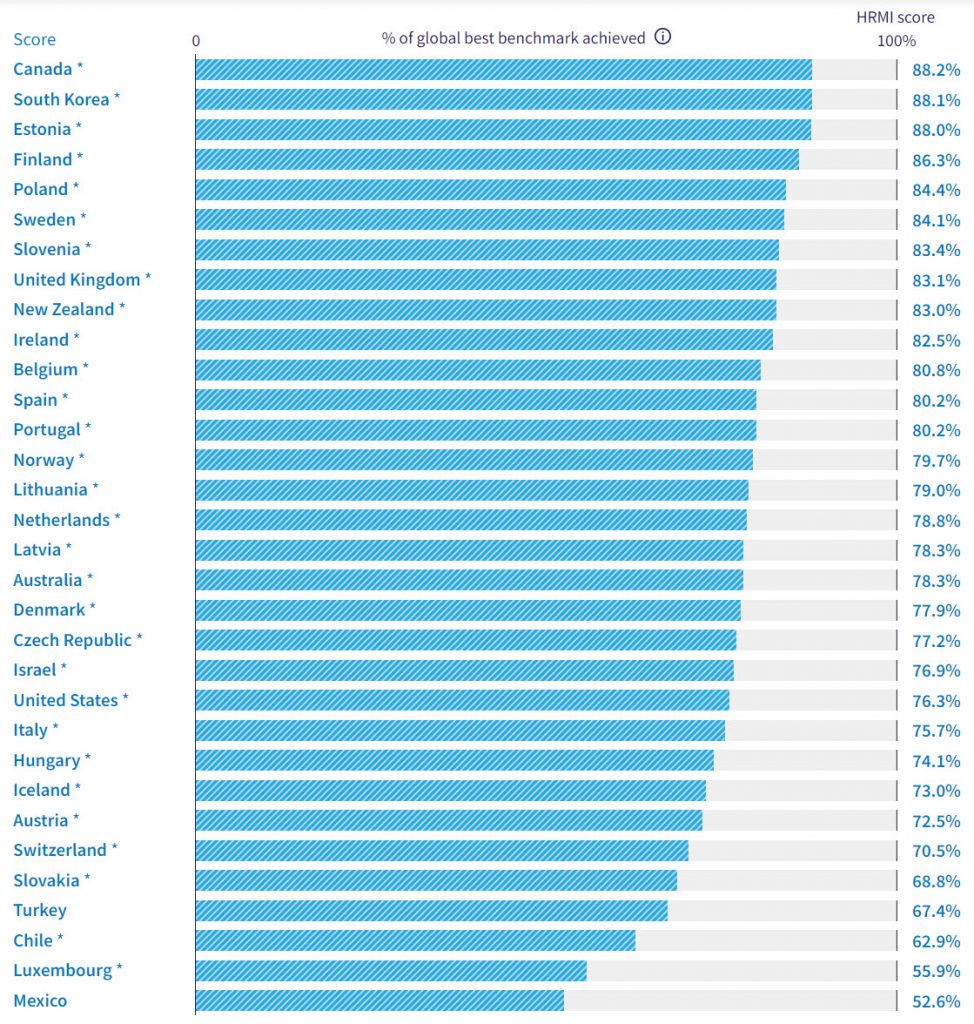

The US rates, on this measure, 22nd out of 32 OECD countries with HRMI scores. Canada, on the other hand, enjoys the highest score of all countries. This suggests the US could learn a great deal from its northern neighbour about effective education policies.

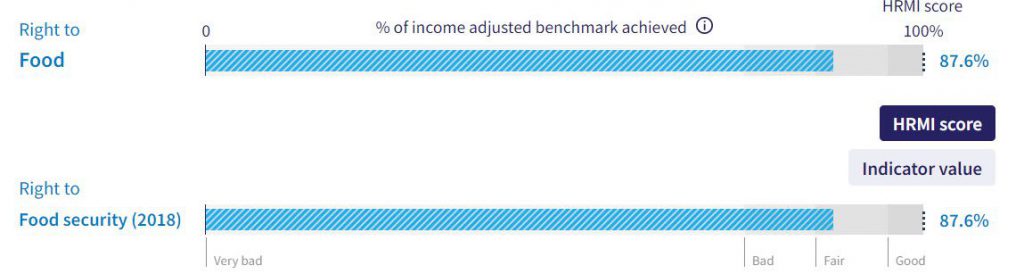

HRMI measures food security to produce a performance score for the right to food. At 87.6%, this is the US’ highest score among all rights for which data is available. Troubling, however, is the fact that the US is nowhere near 100%. This suggests that many people cannot afford food, and may even experience chronic hunger.

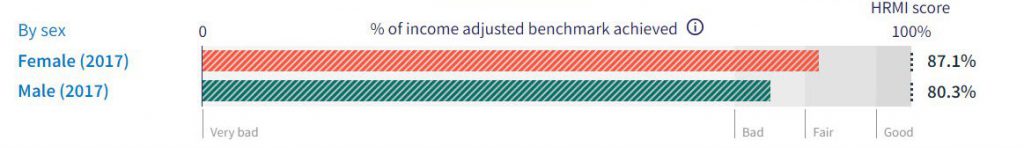

The US 'right to health' score falls in the ‘bad’ range, at 81.3%. This right is based on the idea of more adults and children living longer. HRMI scores the performance on adult health using an indicator measuring the likelihood that a 15-year-old will live to the age of 60. The US’ performance for men is ‘bad’, while the performance for women is ‘fair.’

Similarly, HRMI scores the performance on child health based on an indicator measuring the likelihood that babies of either gender will survive to the age of five. The scores for both genders barely reach the ‘good’ range.

The right to housing is measured by more than one metric. One of these is safely managed sanitation, defined as the percentage of people living in homes with improved sanitation facilities, where waste is safely removed. The score for this right in the US is 88%, which falls in the ‘fair’ range.

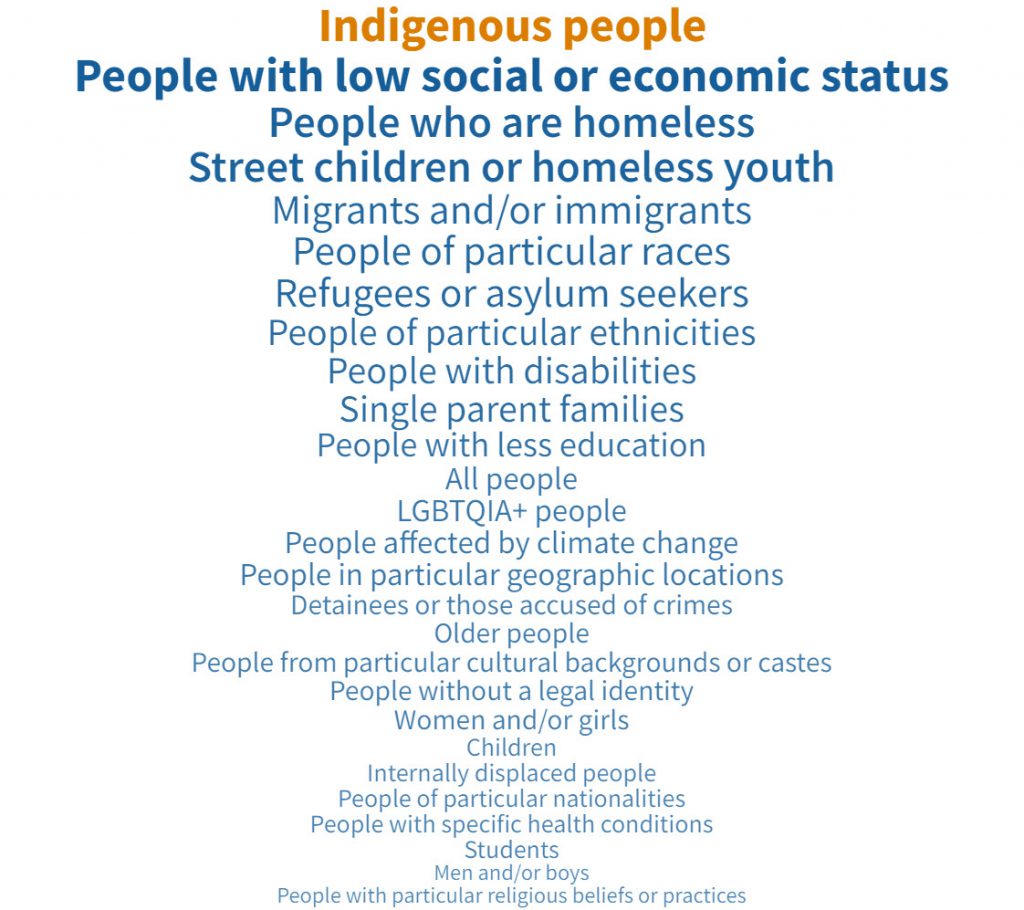

HRMI's yearly human rights survey also reports that 75% of US human rights experts believe indigenous people and those with low social or economic status are at particular risk of having their right to housing violated.

The survey also finds the pandemic has had a profound impact on all groups' ability to enjoy their right to housing. When asked to provide more context about who was particularly unlikely to enjoy their right to housing in 2020, respondents mentioned that:

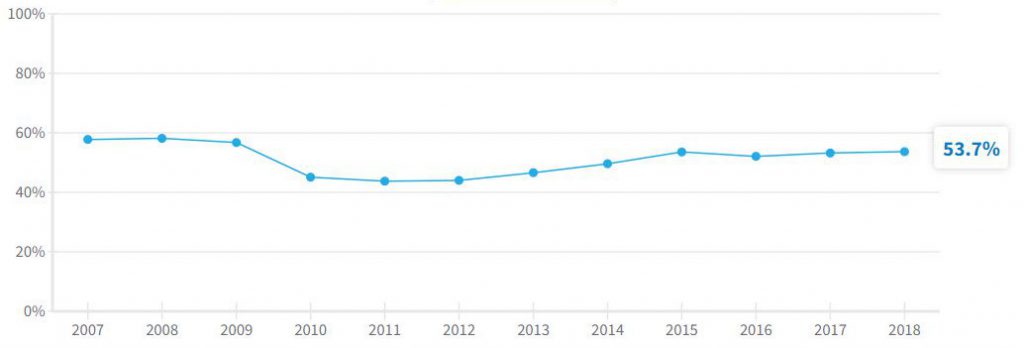

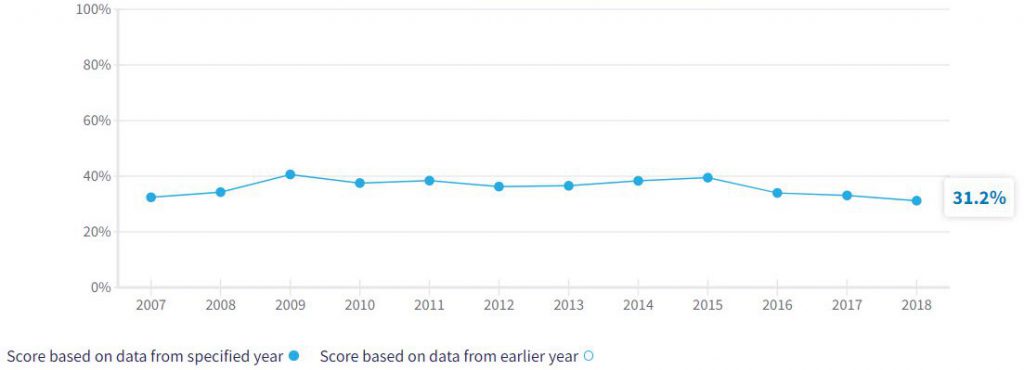

The US fails in its performance on the right to work, with a score of 53.7%.

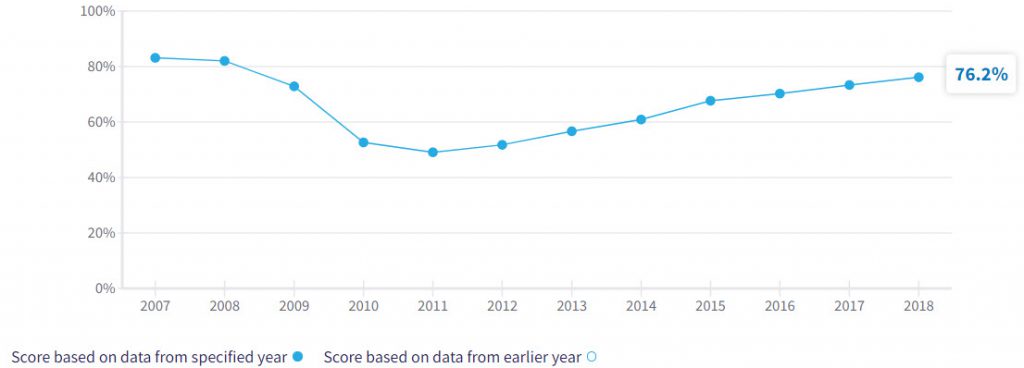

The score is further evidenced in the following two graphs, which reveal that the US performance in ensuring a fair (relative) income is dismal, and worsening. Meanwhile, the country's performance in ensuring people have a job has not fully recovered since the Great Recession of 2008. The pandemic will only have worsened the situation, bringing higher prices for goods and services, and the loss of jobs.

The conclusion from the HMRI scores is stark. The US has been and is failing to meet its human rights obligations in relation to education, food, health, housing and work. And we shouldn't forget that HMRI scores and numbers represent the experiences of real people in the US.

Put another way, if the US used its resources in an efficient, progressive manner, its population could make significant gains. Some of those gains would be:

Given the dismal state of US human rights, the Democrats in power could make great gains if they showed stronger political will to craft a progressive agenda addressing these shortfalls.

Time, however, is of the essence. The looming 2022 midterm elections could change the political landscape. As it stands, many Americans continue to be denied their basic human rights.

The full HRMI dataset is available to download for free from Rights Tracker