So-called 'developing countries' enjoy special rights in world trade. But it is the countries themselves that decide whether they want developing country status, which 'developed countries' increasingly contest. Till Schöfer and Clara Weinhardt suggest three ways out of the developed-developing country stalemate

Who is a developing country? This question, while simple, has recently taken centre stage in global trade politics. In the World Trade Organization (WTO), developing countries can access a catalogue of special legal rights, collectively referred to as Special and Differential Treatment (SDT).

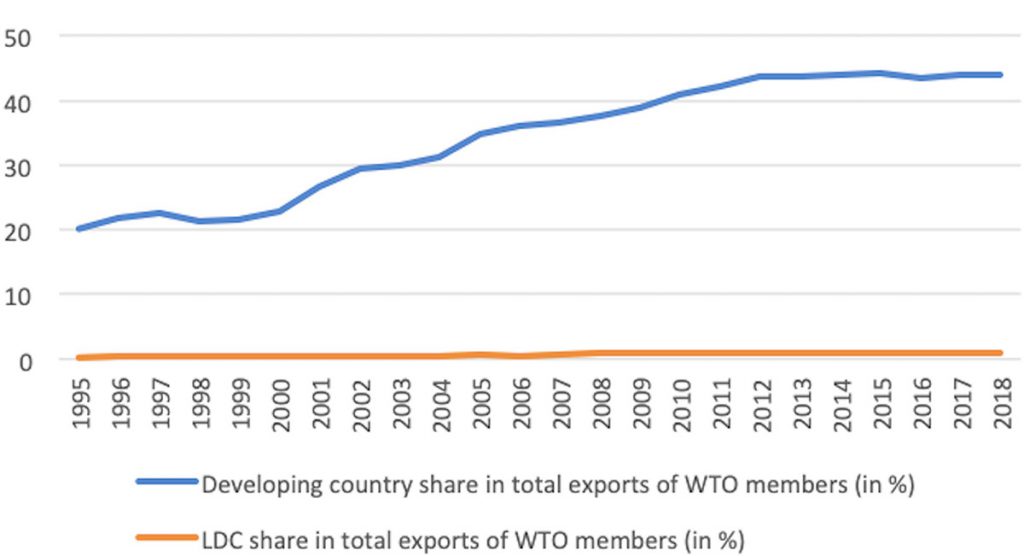

Yet whether emerging economies like Brazil, India and China should still be able to claim these flexibilities has become fiercely contested. The inability to resolve this seemingly simple matter of definitions has not been without political ramifications. In the WTO, the group of developing countries increasingly competes with other groups of disadvantaged countries for special rights. The resulting fragmentation contributes to the unmaking of the North-South distinction as a central ordering principle in global trade politics.

The distinction between the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ – or developed and developing countries – has been central to world trade politics since decolonialisation. In the 1960s and 1970s, developing countries successfully pushed for the inclusion of special rights in the world trade regime. The idea behind these rights is that countries in a disadvantaged position in the global economy are compensated with flexibilities that allow them to open their markets at a slower pace.

Examples are more flexible transition schedules, promises of technical or financial assistance or less stringent liberalisation commitments. A developed country WTO member, for example, must cap its subsidies at 5% of the value of production. Developing countries have more space, with a cap of 10%.

The increasing economic heterogeneity of developing countries that have access to special rights has led to calls for reform

The increasing economic heterogeneity of developing countries that have access to these special rights, however, has led to calls for reform. Many of these calls focus on the introduction of clear-cut criteria to define who counts as a developing country. So far, there are no such definitions. The WTO allows its members to 'announce for themselves whether they are “developed” or “developing” countries'. This unusual approach contrasts with other global regimes, in which socio-economic criteria determine who counts as a developing country.

Sticking to self-declaration complicates international trade legislation. The United States and other major developed country members are unwilling to grant special rights to countries such as China, India and Brazil, which declare they belong to the group of developing countries.

In 2017, the then US Trade Representative prominently complained to the WTO that:

there is something wrong, in our view, when five of the six richest countries in the world presently claim developing country status

robert lighthizer, US Trade representative, 2017–2021

The binary distinction between developed and developing countries is portrayed as outdated, given the increasing economic heterogeneity of the latter group.

To cope with the conundrum of who qualifies for special rights, three possible approaches exist. Firstly, negotiators at the WTO could attempt to shrink the developing country group. They could do this by finding a formula that identifies core characteristics of a developing economy. Alternatively, they could create a list that explicitly defines the beneficiaries of rights set aside for weaker economies.

Second, the core logic of differential treatment is that traders of different sizes should have different rights and obligations. We could take this logic further than the North-South divide. At present, trade politics bifurcates into two camps, each with their respective set of rules. Trade legislation could ‘individualise’ commitments by customising the application of agreements to the specific circumstances of individual countries. A similar approach was adopted in the Paris Climate Agreement.

Thirdly, trade law could refocus future differential treatment on sub-groups of developing countries. The use of special rights by these narrower sub-groups may be more readily stomached by the wider WTO membership. Special rights would then become increasingly fragmented and decoupled from the binary North-South distinction.

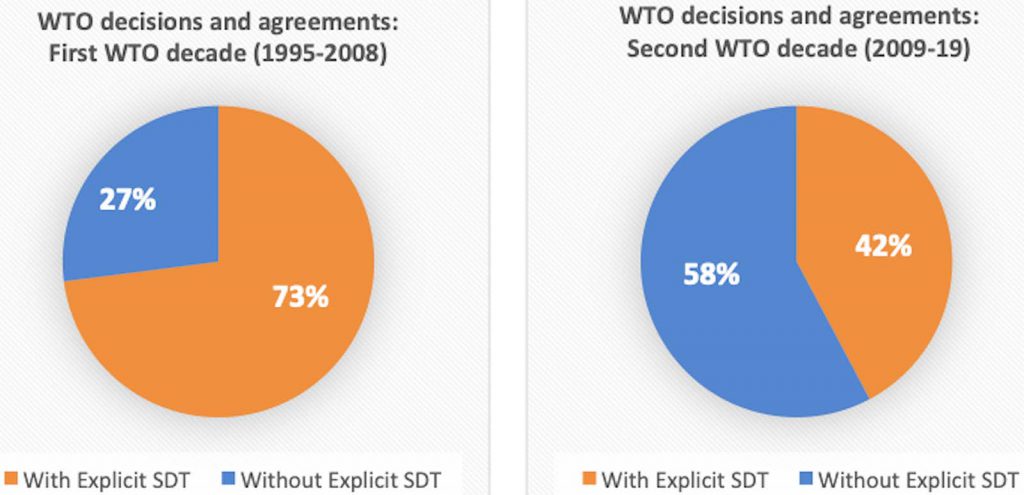

So far, WTO members have been unable to agree on a reform of differential treatment. The third option of fragmentation has therefore prevailed. This trend becomes most visible in a shift away from granting special rights to the contested group of self-declared developing countries.

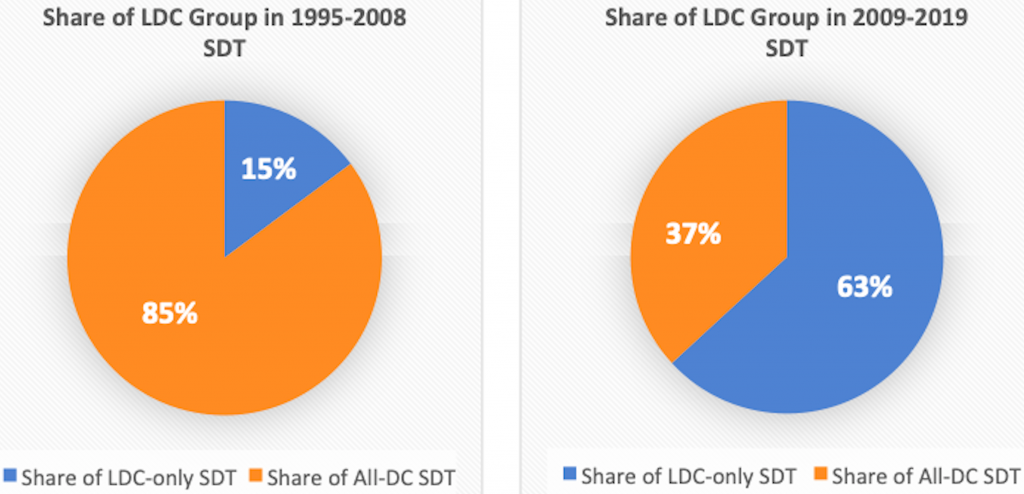

Instead, special rights are increasingly reserved for the marginalised group of Least Developed Countries (LDCs). In the first decade of the WTO, such 'LDC-only' legislation on differential treatment made up only 15% of decisions and agreements. By the 2010s, this subset of provisions had increased to more than 60%; see the figures below.

Precisely because of their position on the margins of world trade, granting policy space to LDCs is less costly for developed countries. Moreover, according to the UN definition of LDCs, such countries graduate from LDC status as soon as their economies reach a certain threshold.

At the same time, WTO members are increasingly unable to come to terms with the reform of the WTO system of special rights for developing countries. This contributes to the marginalisation of such rights. Over the past decade, when negotiators have been able to get decisions passed, they are less likely to incorporate special rights for developing countries. See the pie charts below.

Individualisation has also seen some sporadic successes, chiefly in the Trade Facilitation Agreement (2013). In effect, this agreement customised special rights to individual countries rather than creating broad, one-size-fits-all rights for the group of developing countries. So far, however, this model has not become dominant in WTO legislation.

In 2013, the Trade Facilitation Agreement customised special rights to individual countries

WTO Members will need to decide what changes to business-as-usual they can stomach. On the one hand, attempting to define what is and is not a developing country has thus far proved fruitless. On the other hand, individualisation, while promising, has yet to remedy the stark divides that still exist in issue areas beyond trade facilitation.

If neither of these options gains ground, fragmentation will most likely continue. In future, the WTO will reserve Special and Differentiated Treatment chiefly for Least Developed Countries. This means that developing countries that are neither LDCs nor ‘emerging’ are likely to lose out.

This blog piece builds on the authors' recently published research findings in Third World Quarterly.