This month marks ten years since the adoption of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Yet there is little cause for celebration: progress has been dismal. Benjamin Faude and Jack Taggart argue that the global governance of the goals has undermined progress. They warn that rather than achieving transformative change, SDG governance risks entrenching the beleaguered status quo

This September marks ten years since the adoption of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Getting agreement on the goals was itself a remarkable achievement. The SDGs sought to overcome the limitations of the Millennium Development Goals, and ushered in a truly global agenda. They apply to all nations, regardless of income, and they link economic development directly to environmental and social challenges. Many people saw them as the most ambitious, inclusive, and coherent programme yet for achieving sustainable development at global, national, and sub-national levels.

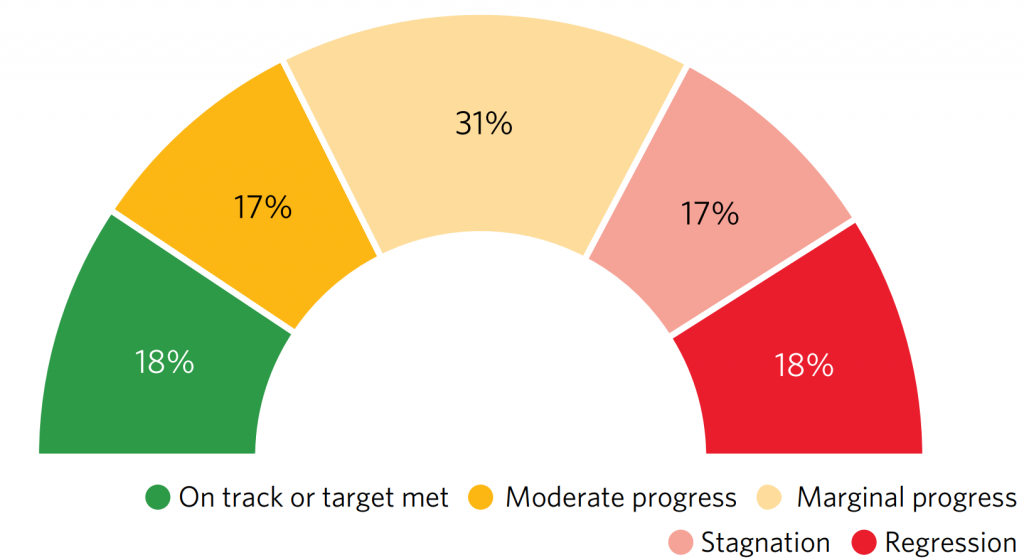

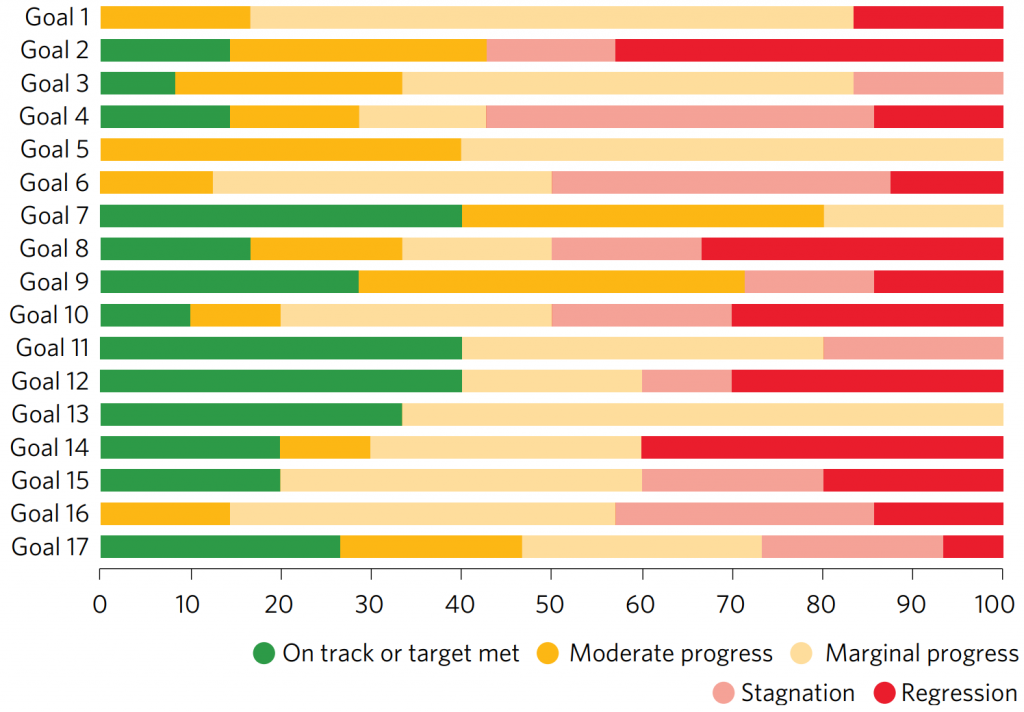

A decade later, however, and the SDGs, along with multilateralism more broadly, are in a sorry state. To each of the 17 SDGs is attached a set of specific targets, the number of which varies from goal to goal. The 2025 SDG Report reveals that only 18% of these targets are on track. More than a third have stalled or regressed. On the key goal to eliminate extreme poverty, revised estimates reveal more people living in extreme poverty today than in 2015. With just five years left until the deadline, there is little cause for optimism.

Percentages do not add up to 100 due to rounding

There are many reasons given for such lacklustre progress. Some point to substantive contradictions within the agenda itself, such as the commitment to market-led growth alongside ecological sustainability. Others point out how compounding crises, including climate breakdown and the lingering effects of the pandemic, have slowed progress further.

Rising geopolitical tensions and the advent of a Second Cold War have also undermined collective, principle-driven agendas. Right-wing populism and economic nationalism, meanwhile, have gained ground over principles of, and political will for, multilateral cooperation.

‘Billions’ of public aid was meant to attract ‘trillions’ in private investment. Private capital, however, has shown little desire for financing the goals

On the latter, the advent of a Second Trump Administration has seen official statements from the US Mission to the UN that ‘globalist endeavours like Agenda 2030 and the SDGs lost at the ballot box… the US rejects and denounces the SDGs, and it will no longer reaffirm them as a matter of course’. Others highlight the failure of the financing model. ‘Billions’ of public aid was meant to attract ‘trillions’ in private investment. Private capital, however, has shown little desire for financing the goals at scale.

While these headwinds have slowed progress, the institutional structure of SDG governance also demands scrutiny. Does the governance system inaugurated by the goals help or hinder their realisation? At their launch, commentators hailed the SDGs as an innovative approach to global cooperation. They rest on voluntary commitments and ‘global governance by goal-setting’ rather than binding rules. Governance is also distinctly hybrid. Treaty-based multilateral organisations such as the UN, WTO, and OECD work with informal bodies like the G20 and thousands of transnational partnerships in pursuit of specific goals and targets. The UN’s own Partnerships for the SDGs platform records more than 5,500 multi-stakeholder initiatives involving states, corporations, NGOs, and local organisations.

In theory, SDGs' 'hybrid' governance structure has potential benefits, such as institutional diversity. But in practice, the risks of such diversity have outweighed the benefits

In theory, this ‘hybrid’ governance structure possesses potential benefits. Institutional diversity, for instance, could better match the complexity of sustainable development challenges and broaden participation. In practice, however, the risks of such diversity have outweighed the benefits.

Our Special Section in Global Policy shows that SDGs have indeed enabled comprehensive issue coverage and widened opportunities for participation. Soft forms of governance, however, have reinforced, rather than transformed, existing power structures.

One contribution to the Section demonstrates how orchestration dynamics privilege more visible and powerful Western-dominated organisations like the OECD, sidelining less prominent organisations from the Global South. Another article reveals how aid donors have exploited the voluntary nature of the SDG’s institutional frameworks to sidestep their commitments to Southern recipient ownership of their development agendas. A third contribution shows how UNEP’s support for SDG 17 and corporate-led multi-stakeholder initiatives in plastic governance, linked to SDG 12 on Responsible Production and Consumption, are a Trojan Horse for entrenching petrochemical interests in governance, thereby weakening prospects for more stringent regulation.

Another article recognises that opportunities for participation in sustainable development governance may have expanded, particularly among non-state actors. But this piece also highlights how ‘inclusion’ in SDG governance is increasingly conflated with the production of data and indicators, transforming participation into a mere technocratic exercise. And the final contribution to the Section uncovers how hybrid, multi-stakeholder partnerships under the SDG agenda often extend neoliberal norms and shallow forms of hegemony, rather than empowering transformative alternatives.

Together, SDG governance risks enabling co-optation rather than empowerment, and tokenism over transformation. Its institutional diversity allows powerful actors to cherry-pick the institutional forms that suit their interests. But this is undermining effectiveness and accountability at the very moment ambitious global action is needed most.

Faltering political will for the SDG agenda makes major reforms to SDG governance unlikely. This is particularly the case among Western powers, many of whom are cutting their aid budgets. Yet as the US and others step back from leadership on the remaining and post-2030 development agenda, China is stepping forward. China frames its bid for developmental leadership around ‘true multilateralism’ and a reinvigoration of UN-centred development agendas, including the SDGs.

As the US and others step back from leadership on the SDGs, China is stepping forward. Its bid, however, is tied to a less liberal conception of world order

China may also push for traditional multilateral structures over institutional innovation and diversity. This, in turn, may avoid the risks of more ‘hybrid’ governance that we have described. China's bid, however, is also tied to a less liberal conception of world order, and eschews political and civic rights in the development agenda.

Even so, China’s contributions are unlikely to close the gap between SDG ambitions and the structures needed for transformative change. In the meantime, progress is likely to remain sporadic at best. What is at stake is not only the success of the SDGs themselves, but also the very idea of collective global agendas as a mode of cooperative governance. This is an idea and a practice that may, in hindsight, prove a brief historical aberration.