Coronavirus dominated the Dutch elections to the virtual exclusion of all else. The outcome, write Joop van Holsteyn and Galen Irwin, is a parliament with a record number of parties. Although the current coalition has sufficient seats to return to power, this may not happen. The Liberal Party again has the biggest share, and it is likely Mark Rutte will return as Minister-President

Although there was early discussion of postponing the March 2021 Dutch parliamentary election, it was eventually held as scheduled. Nevertheless, there has never been an election in the Netherlands in which one factor has been so omnipresent.

Coronavirus affected all aspects of the election, from its organisation, to the campaign, and the results. This didn't appear to hinder outgoing Minister-President Mark Rutte’s Liberal Party, which was returned with the biggest share of seats. Rutte is therefore the most likely candidate for the top job.

Exact figures are now available, and turnout was high, at almost 80%. This is above average for Dutch elections in this century. High turnout may have been partly due to special corona voting provisions. Voters over the age of 70 received postal ballots, and voting was extended to three days from the usual one. The number of proxies that could be cast was increased from two to three.

Amid the pandemic, parties had no choice but to carry out their campaigns almost entirely through the media

Government pandemic regulations also affected party election campaigns. Dutch campaigns are generally group events. Parties pass out literature at local markets, hold rallies, or gather in rented halls for presentations and debates.

In 2021, parties had no choice but to carry out their campaigns almost entirely through the media. Personal observation suggests there have never been so many full-page party newspaper adverts, and ads on the radio and television. Many parties also developed a strong social media presence. The exception was the right-wing populist Forum for Democracy, which continued to conduct rallies.

Political parties conducted their election campaigns entirely within the frame of coronavirus. This put certain opposition parties at a disadvantage. Since the beginning of the pandemic, in typical Dutch fashion, there have been attempts to achieve broad support for coronavirus measures. The result is that virtually all parties gave their support in parliament.

Without major dispute over the restrictions, corona became less the focus of discussion than a cloud that hung over all debate. Some parties did attempt to introduce other campaign issues – the environment, healthcare, the economic impact of the pandemic, Europe – but none gained traction with the media or the electorate.

Without major dispute over coronavirus restrictions, the pandemic became less the focus of discussion than a cloud over all debate

Forum for Democracy, which consistently presented an alternative coronavirus narrative, was the main exception to the rule. It argued that coronavirus was nothing more than flu and that the restrictions to manage it were destroying the country.

In the final days of the campaign, the liberal-progressive D66 also, in a moderate way, picked up on this theme. The party broke from its fellow government coalition members, expressing support for a ‘vaccination passport’ to allow freer movement for those already vaccinated.

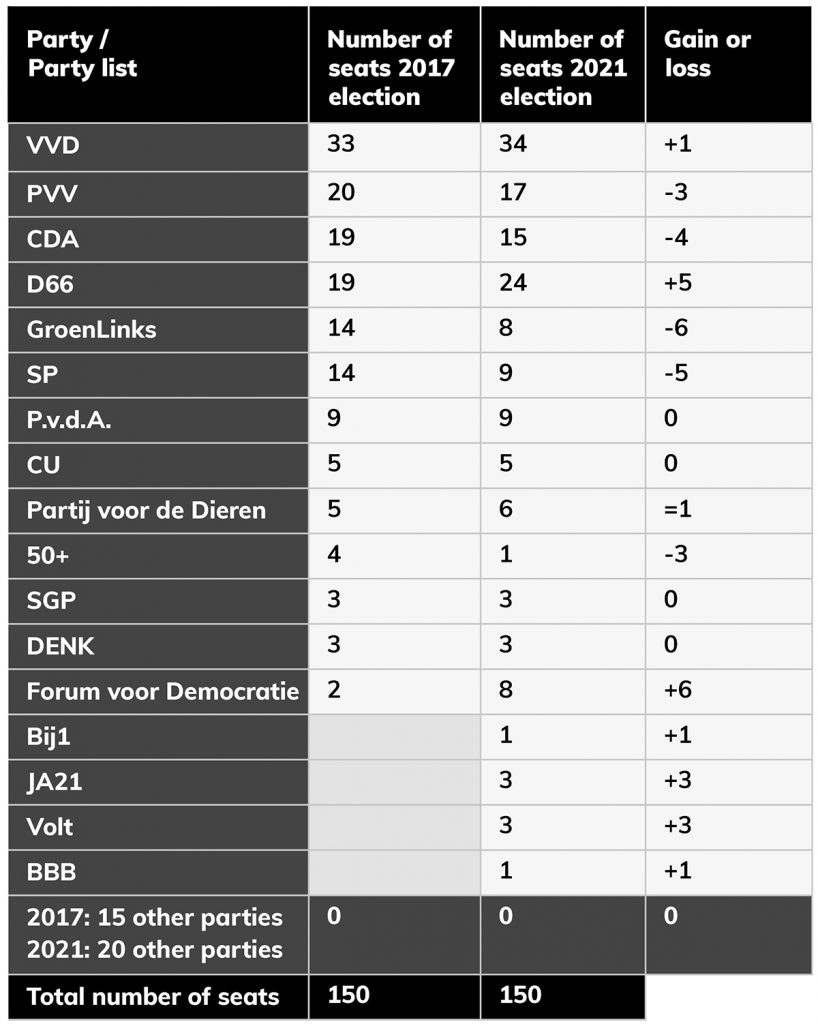

The two parties that had presented alternatives to the current governmental approach to the virus made the strongest gains at the elections. See the Table below.

Forum had emerged as the second largest party in the 2019 provincial elections. Thereafter, it suffered strong internal conflicts, but managed to increase its seats in the lower house from two to eight.

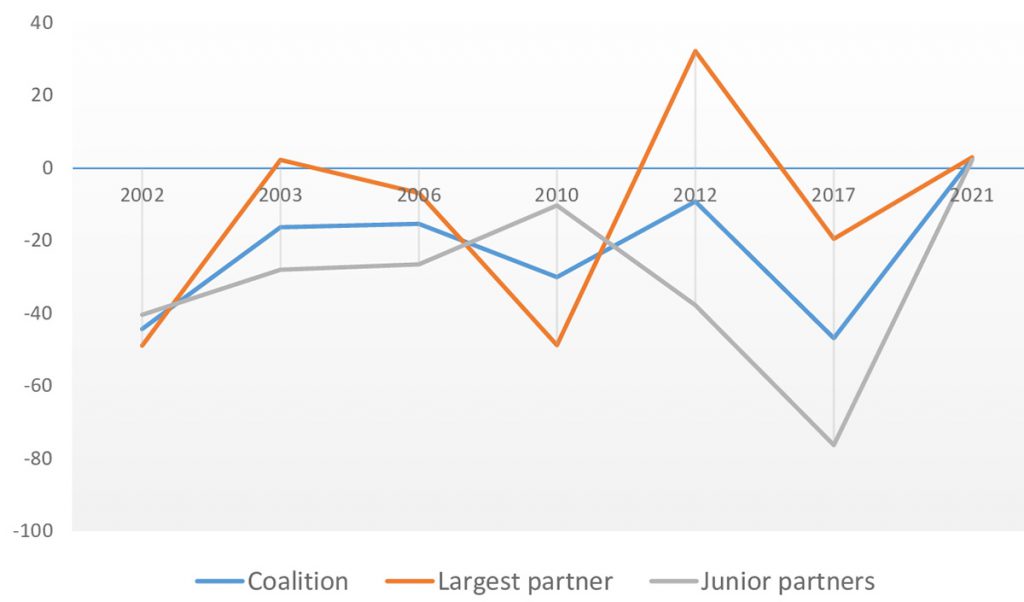

D66 gained momentum in the campaign's final ten days, and grew from 19 to 24 seats. It becomes the second largest party in the 150-seat lower house, helping counteract the general assumption that junior partners lose at a subsequent election. See the graph below. The liberal-conservative Liberal Party (VVD), headed by Prime Minister Mark Rutte, easily remained the largest party, gaining one seat to reach 34.

The Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), which was a member of the government coalition, lost 4 seats, and is down to 15. The parties on the left in opposition also suffered badly: the GreenLeft fell from 14 to 8 seats, the Socialist Party (SP) from 14 to 9 and the Labour Party (PvdA) just managed to hold on to its 9 seats. Together, these traditional left-wing parties fell to a postwar low of only 26 seats.

Noteworthy was the entry of four new parties to parliament. JA21 is a conservative offshoot of Forum, Volt is a liberal pan-European party, Bij1 an ethnic anti-discrimination party and the fourth (BBB) is a farmers' party exploiting the urban-rural divide.

It was clear from the outset of the election that the Liberal Party would be the largest party and that Rutte would most likely return as Minister-President. To a large extent this removed from the calculation of voters the question of who would obtain power, freeing them to vote for parties that represent their ideas and interests.

As a result, the number of parties in the Second Chamber has increased to 17. This is the highest number since 1918, and includes several single-issue parties, along with parties representing very specific interests. The challenge now (while the former Cabinet stays in office on an interim basis) is the formation of a Cabinet based on a majority of the seats in Parliament. This is usually a long and tedious process that can take up to six months. The outcome remains uncertain.