How are states and intergovernmental organisations adapting to new patterns of vulnerability created by the pandemic? Daniela Irrera suggests that future humanitarian systems must involve non-state actors alongside their governmental counterparts

The Covid-19 pandemic is affecting the lives of millions. For those living in troubled circumstances, particularly in regions disturbed by conflict, instability and deprivation, conditions are being exacerbated.

In Syria and Yemen, civilians are suffering the effects of war alongside lack of access to testing and health facilities.

In Palestine, people are facing the pandemic alongside a proxy war. Reduced funding and governmental support mean international agencies are struggling to provide basic services.

In Africa, Latin America and South-East Asia, many household economies are based on community mobility and remittance networks. These networks have been overwhelmed by scarce resources, poor social protection, and deficiencies in democratic institutions.

In the Middle East, local actors have denounced the decision of Western donors to divert funds from initiatives such as peacebuilding – previously considered a priority – to support emergency health measures.

In Greece, thousands of people continue to live in crowded migrant camps. As the fire in the Moira camp made clear, they still lack proper protection.

Conditions are the same for refugees displaced on the Bosnian side of the Croatian-Bosnian border. These people are attempting to survive the effects of the Croatian authorities’ pushback, regardless of health provision.

The new military regime in Myanmar is repressing current protests in the most brutal manner. The regime is using national security to justify its total disregard for the needs of Rohingya communities in the pandemic.

Vulnerable people have always suffered the consequences of civil and proxy wars, political violence, underdevelopment, tyranny, and inequality. The pandemic exacerbates the effects of all these.

Covid-19 reveals that, despite good intentions and a commitment to accountability, the global humanitarian system is far from efficient

Covid-19 reveals that, despite good intentions and a commitment to accountability, the global humanitarian system is far from efficient. Clearly, it's important to tackle corruption in the allocation of funds, and the lack of transparency in relations with local organisations. But we must also reconceptualise strategies and priorities, and coordinate all competent actors effectively.

We need, in short, to rethink ‘vulnerability’.

Current public discourse focuses on resilience. Yet vulnerability is the element around which more sophisticated tools should be developed.

Intergovernmental actors' definitions of vulnerability vary. The United Nations bases them on external and internal dimensions, the European Union on broad categories of people most subjected to hazards and dangers.

Yet the global humanitarian system, as it has developed, cannot always respond to crises in the common interest of society and in accordance with humanitarian principles. It cannot, therefore, prevent the marginalisation of the most vulnerable.

Over recent decades, certain groups have suffered disproportionately: economic migrants; refugees and asylum seekers; civilians in conflict zones and those in poor, undeveloped areas. These are the people on whom policies need to focus, particularly during a pandemic.

In the name of national health protection, funds are being diverted, borders closed, and repatriations enforced. This shows how states and intergovernmental organisations are failing to protect people – and to understand who should be protected. More importantly, they are failing to adapt and expand protection according to specific crises and needs.

The provision of humanitarian relief by non-state actors, particularly civil society organisations and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), has developed to fill the gap left by governmental actors. The pandemic has heightened the visibility of this mix of traditional and innovative roles.

In unstable and poor countries, NGOs have begun to play intermediaries. They are helping people survive lockdowns by compiling lists of beneficiaries and cooperating with local authorities to guarantee tests and medical services.

In conflict zones, NGOs are assisting civilians and mitigating the effects of violence associated with the virus

In conflict zones, NGOs are assisting civilians and mitigating the effects of violence associated with the virus. NGOs working with migrants and refugees have denounced the brutal effects of closures and solicited states to provide more protection.

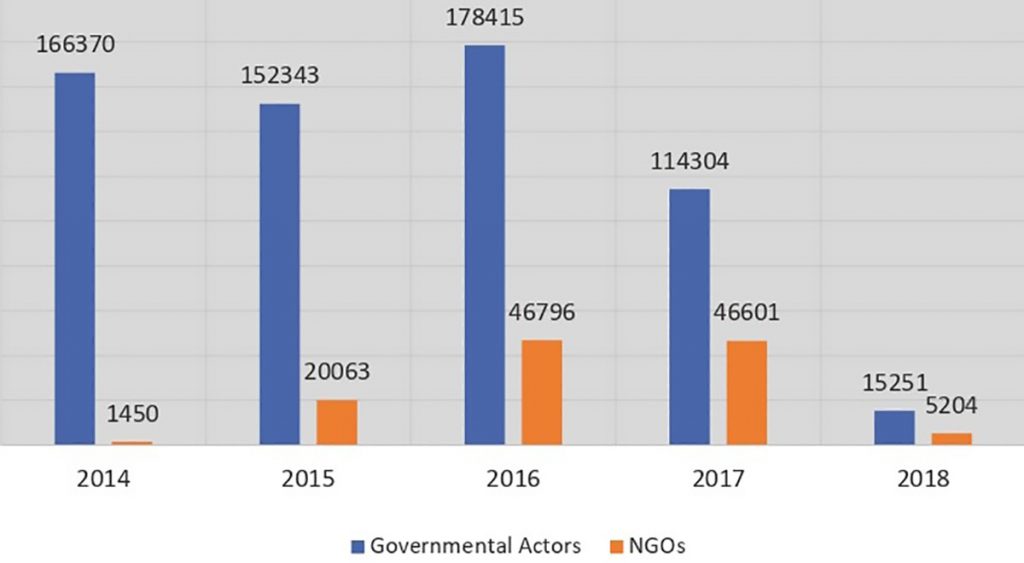

The biggest achievement is the innovative practice of non-governmental search and rescue (SAR) operations. Since autumn 2014, NGOs have complemented existing EU and state SAR operations with their own vessels. Proportionately, NGOs have significantly increased their share of people rescued since 2014, compared with government actors.

Search and Rescue Operations by Governmental Actors and NGOs, 2014–2018

The pandemic is pushing organisations at all levels to retarget their usual work into emergency relief. In parallel with service provision, NGOs and other civil society organisations are monitoring abuses of power, illiberal practices, unequal medical treatment, illegitimate asylum denial, and forced return.

The pandemic has exposed governmental failures and incapacities. In so doing, it offers lessons to be learned. Policies and practices developed to protect people and alleviate vulnerability have collapsed in the face of a global emergency.

the global humanitarian system is made up of two components: one governmental, one non-governmental. Both are necessary and mutually interdependent, although they often conflict

We must reconceptualise and refocus global and regional strategies to identify real priorities. NGOs' activities show how the global humanitarian system is made up of two components: one governmental, one non-governmental. Both are necessary and mutually interdependent, although they often conflict.

Defeating Covid-19 will not automatically solve these problems. In a post-pandemic world, vulnerable people will be numerous and demanding. Over the long term, we need a combination of humanitarian responses, development programmes, peace promotion and protection measures.