The European Union has withdrawn from search and rescue in the Mediterranean, outsourcing its border management to a third state and effectively criminalising NGOs that step into the gap. This, writes Luca Doll, is a policy that needs urgent review

In early December 2020, the European Anti-Fraud Office launched investigations into Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency. Allegations range from pushbacks — unlawful practices aimed at stopping migrants from reaching EU waters — to the harassment of migrants, and misconduct in the Aegean Sea.

These allegations sit alongside other alarming reports on the EU‘s management of its maritime borders. Throughout the past decade, the EU has drastically decreased its capacity to search and rescue (SAR) at sea. It has criminalised civilian actors seeking to fill this gap, and outsourced border management to the Libyan Coast Guard.

Such activities reflect a gradual change in the EU’s approach to maritime migration, from passiveness to active restrictiveness. And these developments have proved fatal for those attempting to cross the world's deadliest border: the Mediterranean Sea.

We can trace European disengagement from SAR back to 2013. In October that year, a converted fishing vessel attempting to cross the Mediterranean sank near the Italian island of Lampedusa. More than 360 migrants lost their lives.

In response, Italy launched its Mare Nostrum search and rescue mission. This lasted until late 2014, and rescued more than 150,000 migrants shipwrecked and stranded at sea.

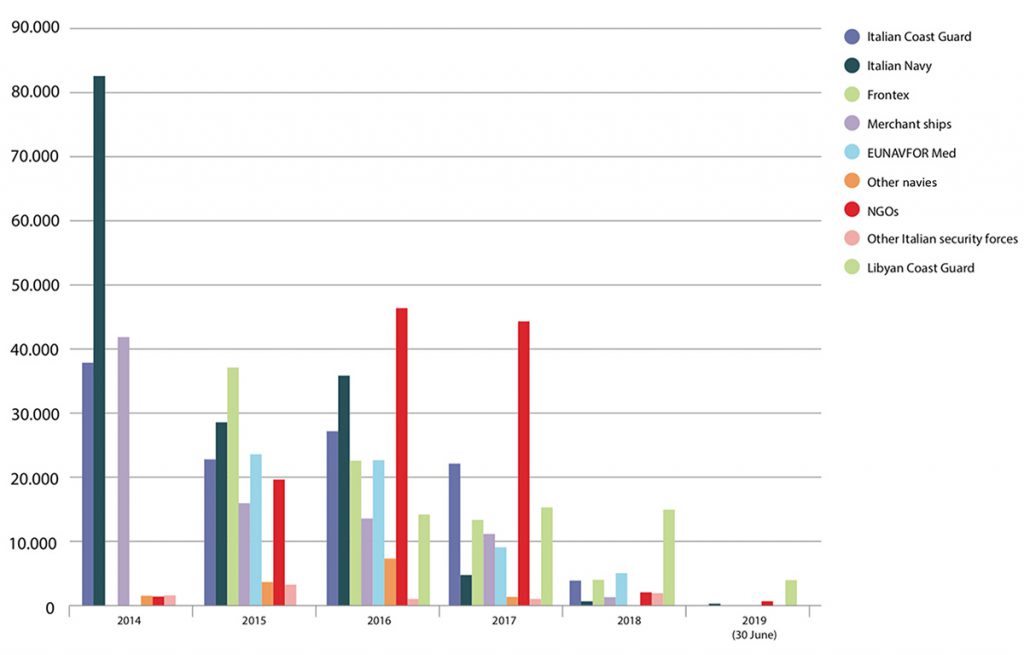

Mare Nostrum was succeeded by Frontex-led operations Triton and Themis, alongside EU military-led initiative Operation Sophia. The primary focus of all these operations was maritime law enforcement in the Mediterranean. SAR did remain part of their objectives. But these operations' ultimate aims were to control borders, train Libyan Coast Guard, and enforce the UN arms embargo to Libya.

By 2019, Frontex and military-led operations had withdrawn naval power and SAR-related activities. This highlighted the already limited focus on maritime rescue, and offered evidence of increasing EU disengagement in this field.

Operation Sophia was succeeded in March 2020 by Operation Irini, which has no SAR mandate.

These widening gaps in SAR coverage have been met with rising casualties. Since 2014, more than 20,000 people have died trying to cross the Mediterranean. This figure does not include unrecorded cases, so is likely an underestimate.

To counteract the EU’s withdrawal from search and rescue, civilian actors and NGOs stepped in to fill the gap. This had dire consequences for civil society, leading to crackdowns on activists and the criminalisation of organisations involved.

One notable case was the Italian government’s prosecution of German ship captain Carola Rackete, accused of smuggling migrants to Lampedusa. The court invoked the duty to render assistance enshrined in Article 98 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. It ruled that Rackete's offences were not substantiated.

Criminalisation of NGOs engaging in SAR chimes with the EU’s general aims to eliminate ‘pull factors’ encouraging immigration to Europe. European politics frequently depicts (civil) SAR in the Mediterranean as a pull factor. But this reinforces a dangerous narrative in public discourse.

An argument used repeatedly by policymakers is that SAR aids traffickers and their business. There is a prevailing belief that smugglers assume they needn't ensure their vessels make the crossing safely — they gamble on SAR to guarantee secure passage. Little evidence exists to substantiate this. A European University Institute study examining migration from Libya to Italy between 2014 and 2019 found:

no relationship between the presence of NGOs at sea and the number of migrants leaving Libyan shores

Sea Rescue NGOs: a Pull Factor of Irregular Migration? November 2019

These activities, and the EU’s ‘outsourcing’ of border management to third parties, discourage NGOs from engaging in SAR.

In 2017, Italy and the Libyan Government of National Accord signed a Memorandum of Understanding, committing themselves to cooperation in migration and border security. This included the training and equipment of the Libyan Coast Guard, provided and funded by Italy and the EU.

Italy oversaw the formulation of a Code of Conduct for NGOs that obliges organisations to cooperate with the Libyan Coast Guard or face legal consequences in the EU. The overarching rationale is to prevent refugees leaving Libyan territories by intercepting them rapidly, soon after departure, and transferring them back ashore.

Fugitives crossing through Libya face arbitrary detention:

they are subjected to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment, […] abuse, including rape, and sometimes sold into slavery

Commissioner for Human Rights, Council of Europe, 15 November 2019

This, alongside the described pullbacks at sea by the Libyan Coast Guard, creates a potentially deadly environment for refugees — an environment partially funded by the EU.

Outsourcing such capacities is a circumvention of the duty to protect those in need, and an evasion of judicial accountability on European soil.

In the de facto absence of a legal framework for refugees, the EU has outsourced border management to Libyan forces. The EU has resigned from, and criminalised, search and rescue operations. This combination invites fatal consequences.

European policymakers must evaluate the implications of their strategies and consider alternative approaches. They should begin by ceasing maritime collaboration with the Libyan Coast Guard, and replacing the persistent criminalisation of civil SAR with genuine cooperation.

Accomplishing this is critical for the EU to meet the standards to which its member states subscribed when signing its treaties. Most of all, it is imperative to prevent further tragedies in the Mediterranean.