The EU did not foresee how autocratisation would unfold in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). But political scientists failed to raise the alarm, too. James Dawson, Lise Herman and Aurelia Ananda show that optimistic assumptions about democratisation misled policy makers and researchers alike

Ten years after Victor Orbán’s constitutional revolution in Hungary, senior EU decision-makers Viviane Reding and Martin Schultz reminisced on camera about the fractures that then appeared in the enlarged EU’s constitutional identity. As Reding conceded, 'No one could imagine' autocratisation within the European Union. Just as revealingly, Schultz claimed 'everyone assumed' that the countries from the 2004 enlargement would uphold their democratic 'contract'.

Faith in a one-way arc of CEE democratisation has not been rewarded

General optimism about the region’s future political trajectory seemingly misled EU decision-making either side of the 5th and 6th enlargements. Faith in a one-way arc of CEE democratisation has not been rewarded. Perhaps the time has come to ask what went wrong.

Prior to the accession of CEE countries, the EU missed several opportunities to strengthen democratic safeguards. In some new member states, it also failed to respond in proportion once autocratisation took hold. Overall, our research finds that, in line with Schultz and Reding's observations, an intellectual climate of optimism appears to have prevailed. The EU placed unwarranted faith in the resilience of institutions that were built largely to satisfy the EU’s own criteria.

Various self-interested actors at EU and member-state levels stymied efforts to strengthen legal mechanisms pre-empting autocratisation. That much is true. But it was only within a broad context of optimism that it was politically possible for the EC to take a permissive attitude to pre-accession monitoring, and for the EPP to protect Orbán into the 2010s.

The climate of optimism rested on three core assumptions, all of which are consistent with rational-institutionalist theorising in political science.

Prior to the accession of CEE countries, the EU missed opportunities to strengthen democratic safeguards, and failed to respond in proportion once autocratisation took hold

First, there was a shared belief that the EU’s carrot-and-stick approach could incentivise CEE politicians to uphold a liberal-democratic institutional order. The EU assumed CEE politicians were rational actors with a utility calculus, and that EU decision-making could meaningfully change this.

This vision, in turn, rested on a minimal understanding of democracy as a 'procedure' guaranteeing free and fair elections rather than as a 'regime' rooted in deeper ethical commitments to a democratic way of life.

Lastly, the EU assumed that socio-cultural dimensions of democracy were secondary to – and derivative of – institutions. The hope was that with institutions in place, the embrace of norms like tolerance and inclusivity would follow in time. Consequently, the EU’s assessment of democracy in Central and Eastern Europe failed to spot democratic failures and autocratisation trends outside institutions.

We wanted to know whether our discipline has tended to support the optimistic analyses of EU policymakers. Overall, we found political science did tend to confirm, rather than check, this climate of optimism.

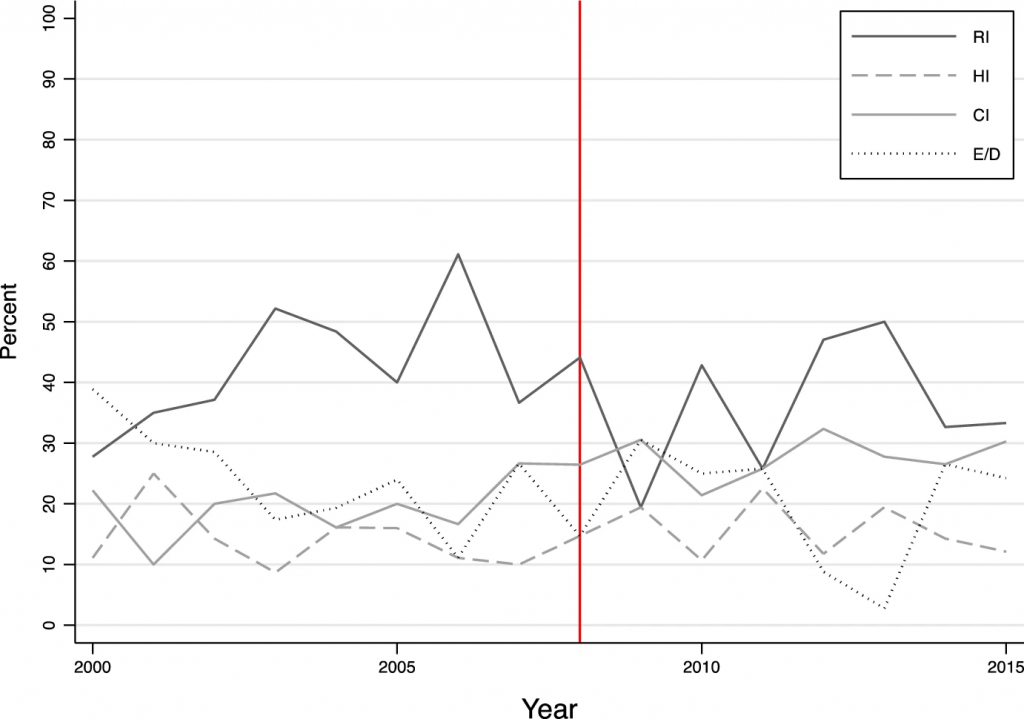

We subjected 500 papers published between 2000 and 2015 to a quantitative analysis. All appeared in top, generalist political science and top post-communist area studies journals. Our entire sample barely tilted positive/optimistic (39.92%) over negative/pessimistic (34.13%). However, our analysis revealed four statistically significant patterns that made optimistic scholarship more visible.

Our research found that political science did tend to confirm, rather than check, EU policymakers' optimistic analyses

As the table below shows, papers examining EU accession, including enlargement and conditionality, were 19 percentage points more likely to be positive. Papers analysing civil society, including minority rights and social movements, on the other hand, tended to be more negative by 17%, despite studying the same countries over the same time period.

| Negative | Neutral / Mixed | Positive | |

| Civil society | 0.17*** | -0.15** | -0.05 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.05) | |

| Government | -0.01 | 0.10* | -0.10+ |

| (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| EU accession / conditionality | -0.13* | -0.07 | -0.19** |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | |

| Political parties / party systems | -0.11 | -0.10* | -0.01 |

| (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Political economy | 0.11+ | -0.06 | -0.06 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| Public opinion | 0.11+ | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Observations | 499 | 499 | 499 |

EU-accession-centred papers received, on average, 25 citations per article more than any other paper topic or subject. Civil society papers received, on average, 18 citations fewer. Thus, disciplinary inequalities of prestige and journal access seem to have rendered more optimistic EU accession scholarship more visible.

| Citations | |

| Civil society | -18.23* |

| (7.68) | |

| Government | -9.79 |

| (7.60) | |

| EU accession / conditionality | 25.25** |

| (8.27) | |

| Political parties / party systems | 17.18+ |

| (9.13) | |

| Political economy | -10.79 |

| (8.98) | |

| Public opinion | 3.43 |

| (9.10) | |

| Observations | 499 |

Papers applying the rational-institutionalist framework were 10 percentage points less likely to be negative. Those employing cultural-ideal frameworks were more negative by 12% compared with all other frameworks. See the table below. In other words: the likelihood of findings echoing the EU’s optimism increased when scholars relied on frameworks closer to the EU’s technocratic proceduralism.

| Negative | Neutral | Positive | |

| Rational institutionalism | -0.10* | 0.03 | 0.07+ |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Historical institutionalism | 0.14** | -0.07 | -0.09 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| Cultural-ideal | 0.12** | -0.11* | -0.02 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.05) | |

| Evaluative / descriptive | -0.11* | 0.12** | -0.02 |

| (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| Observations | 499 | 499 | 499 |

Finally, a boom of rational-institutionalist paper publications peaked in unison with the culmination of the 'Big Bang' EU enlargement period between 2004 and 2007. This represented 61.11% of our entire sample at its peak in 2006.

We need a reassessment of political science’s reward systems that still grant greater visibility to research on formal procedures over informal norms, elite institutions over civil societies, and aggregate data over nose-to-the-ground fieldwork. Lower-prestige categories of research were more prescient in emphasising the cracks through which autocratisation has subsequently emerged.

One lesson for the EU is that it should divert some of the energy currently devoted to checking legal-institutional compliance to more sociologically-aware efforts supporting bottom-up democratisation. Another more general lesson is that while research that aligns with the EU’s own assumptions might be easiest for it to digest, it might not be what the EU needs to hear.