Hard-right ‘TikTok messiah’ Călin Georgescu was leading the Romanian presidential race when suspected Russian intervention prompted the Constitutional Court to annul the elections. Ana Țăranu analyses how the annulment feeds into the Romanian far right's polarising worldview

On 12 January 2025, tens of thousands of protesters gathered in Bucharest in support of former presidential candidate Călin Georgescu. A hard-right independent, Georgescu is now challenging the Romanian Constitutional Court's decision to cancel the first round of the presidential elections, which he won. The Court, however, ruled that there was clear evidence of Russian intervention in his TikTok-centric election campaign. It made its annulment ruling at the very last moment, on the eve of the second round. Indeed, voting in this round had already got underway among the Romanian diaspora – a stronghold of Georgescu support.

All this is evidence of the incremental normalisation of far-right rhetoric in Romania. With Georgescu’s entry into the second round and the coalition efforts of all pro-European parties in a ‘nation-saving’ project, Romanian political life is fundamentally altered. Manichean far-right contestation prevails: pro-Europeans versus sovereigntists, Westernisers versus patriots, elites versus the people.

It is not the first time that far-right mobilisation has exposed blind spots in Romania's political establishment. The far-right Alliance for the Union of Romanians' (AUR) entry into parliament in 2020 was similarly regarded as shocking. Based on targeted online campaigning, AUR won 9% of the votes with a straightforwardly populist electoral platform: the patriotic fight against corrupt political elites, whose servitude towards the West had weakened national sovereignty. The Covid-19 pandemic created a favourable environment for AUR's protectionist, anti-globalist stances, as has war in Ukraine.

AUR has since managed to double its support, winning 18.3% of the votes in the 2024 legislative elections. Unsurprisingly, two new players have emerged in the so-called ‘sovereigntist’ parliamentary bloc: Diana Iovanovici-Șoșoacă’s S.O.S. Romania (founded after her 2021 exclusion from AUR) and POT (Partidul Oamenilor Tineri – The Party of Young People), a consistent supporter of Georgescu. In the 1 December legislative elections, S.O.S. and POT helped push overall support for the far right to around a third.

Most expected the second round of the presidential race to be a run-off between current PM Marcel Ciolacu and George Simion

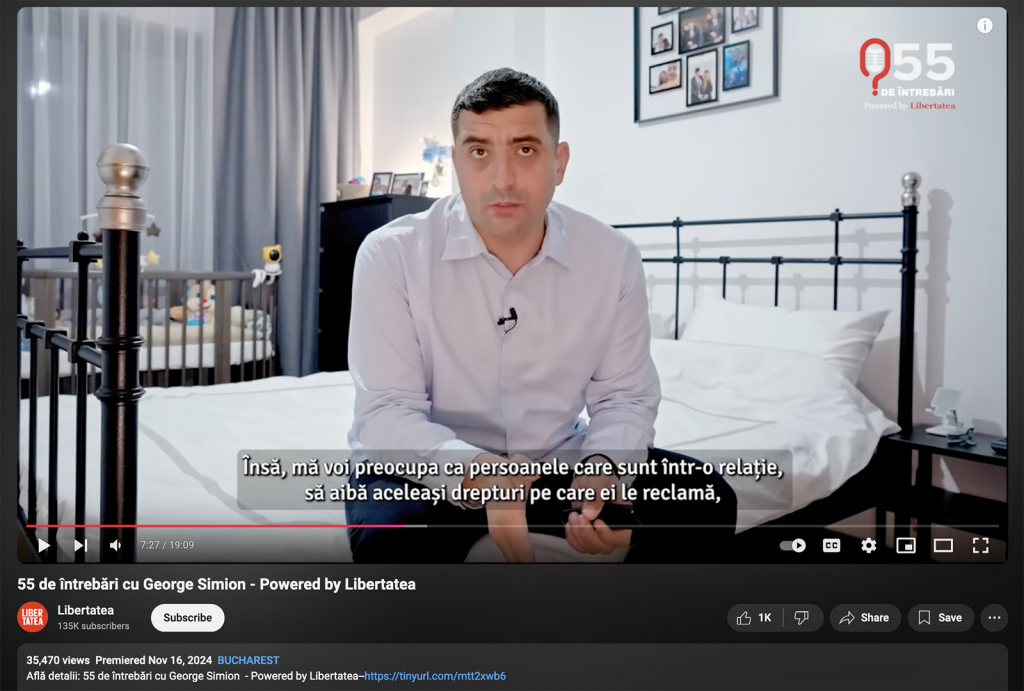

This surge of the far right was not, in fact, unforeseen. Most expected the second round of elections to be a run-off between current PM Marcel Ciolacu (Social Democratic Party) and the far-right George Simion, leader of AUR. Visible in both traditional and online media – his TikTok account has 1.2 million followers –, Simion played by the populist textbook. The fact that he lost to Georgescu shows how far-right normalisation is a double-edged sword.

As a player in mainstream politics, AUR has struggled to moderate its far-right positions without alienating its electorate. A common strategy to mitigate this has been to exclude some party members – notably Șoșoacă and Georgescu. Removed for ‘indiscipline’ and for their public praise of fascist leaders, both went on to secure substantial support and claim the coveted (albeit marginal) position of populist truth-bearers. Simion tried to court the conservative electorate by moderating his stances. Questions on minority rights and NATO membership got favourable answers in his personable TikTok Q&As.

The diffusion of nationalist and conservative rhetoric across the political spectrum complemented his moderation. AUR infused their aggressively nationalist early 2024 campaign with historical imagery and religious symbolism. It seems to have changed the lexicon of domestic politics. Fellow candidates, such as Elena Lasconi, embraced religious symbols, folkloric patterns, and flowery patriotic language across their political communication. Against this common background, Simion’s attempt at Meloni-style populism made him indistinguishable from the ‘system’ candidates. In other words, he became too mainstream.

Simion’s attempt at Meloni-style populism made him indistinguishable from the other candidates: he became too mainstream

Georgescu’s (apparent) disengagement from traditional politics and the media boosted his appeal and the legitimacy of his anti-system mysticism. His central themes were Romanian exceptionalism, economic protectionism, geopolitical ‘neutrality’ (with anti-Ukrainian and Russophile overtones), and the recurrent motif of a common body of the nation, unified finally in an electoral work of God.

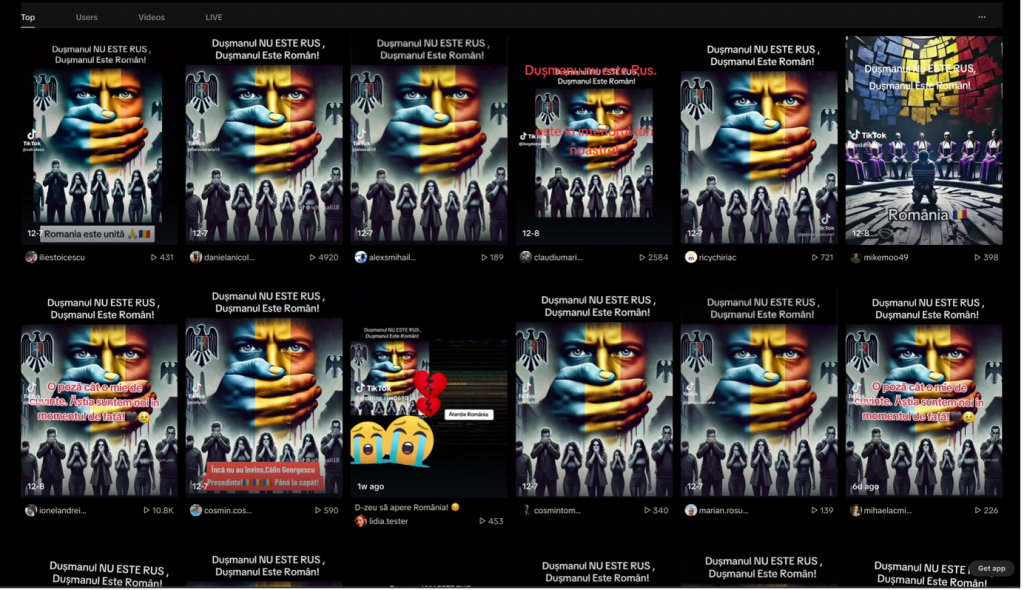

The annulment came as a relief to many, as well as an infuriating confirmation of far-right capacity-building. In an abusive and poorly orchestrated coup d'état, the highly politicised institutions of the ‘system’ swooped in to save it once again. Or so argue Georgescu and Simion, who are interpreting the court's decision as a sovereigntist fight. AUR was quick to launch an online petition 'for free elections'. The petition has reached around a million signatures and is part of its notification of concerns to the Venice Commission. It is saddening for a Romanian patriot, argues Simion in a TikTok video, that it takes external intervention to restore Romanian democracy.

To many Romanians, annulment of the election came as a relief, as well as infuriating confirmation of far-right capacity-building

The paradoxical status of these far-right leaders, who court Western support while claiming complete sovereignty, remains less obvious than the simple narrative around which they rally: the salvation of Romanian dignity from Western degeneration.

That a similar language of national salvation has entered the vocabulary of pro-European parties suggests it is indeed effective. But it also highlights how, ahead of the spring 2025 election rerun, a Manichean narrative of populist contestation is gaining ground, pitting Westernisers against self-styled patriots, or globalist elites against an increasingly endangered people.

Very much besides the point.

The truth is that there is no evidence whatsoever of any „Russian interference”. The Venice Commission ruled that the Constitutional Court cannot simply cancel elections based on „suspicions” or „secret information”.

The rest of the article about the danger of „extremism” is a cover up for the so called democrats who cancelled elections (= democracy).

These are the obvious fascist junta, but activists such as this author, cannot admit that so called „European democratic” parties really brutally cancelled democracy.

times are changing fast and there will be a reckoning. Romania will never buy UE propaganda from now on, the emperor is naked, Bruxelles is the only actor who interfered with our democracy and they just cancelled it cuz they didn t like who won.

Shame on the so called intellectuals who do not see it as it is !

The Government of Romania announce the people are too dumb to vote for the correct canidate, so we will rerun the election till they get it right Democracy European Union style.

One little problem with your narrative it wasn't RUSSIA it was actually the Romania parties themselves promoting the "far right".... The real and most obvious cyberwar opperation run by the Communist block isn't propmoting "Far right", it is making the left believe what they say is far more popular than it actually is i.e. they just hit the like button on even the most ridiculous ideas.

How sore losers who can't win in the domain of ideas look like;

Coming from someone who is not even affiliated or invested in this election I would like to say that in light of recent events, it's become increasingly evident that the cancellation of the Romanian presidential elections under the guise of foreign interference is not merely a misstep but a deliberate act of institutional subversion. This decision, steeped in speculative suspicion rather than concrete evidence, reeks of a desperation from the left to maintain control by any means necessary, forsaking the very principles of democracy they claim to uphold. It is a sophisticated form of political manipulation, where the fear of a far-right victory has led to actions that could be likened to the authoritarian tactics of a bygone era, undermining the sanctity of electoral integrity. This move not only betrays the trust of the Romanian electorate but of European people in general, it also sets a dangerous precedent, suggesting that when ideological adversaries gain traction, the response is not to engage in robust debate or present compelling alternatives but to resort to what can only be described as electoral despotism. The sophistication of this strategy lies in its subtlety, cloaking itself in the narrative of safeguarding democracy while, in reality, it erodes the foundation upon which democratic societies are built. The left fails over and over to extract any knowledge from the people they pretend they represent and continue on with the same failing strategy as they refuse to adjust. What else do you call them but totalitarian technocrats. This is not merely a political maneuver; it's a betrayal of democratic ethos, a clear sign that when arguments fail, some on the left are willing to dismantle the democratic process itself while gaslighting the public. its repulsive to be quite frank.

Everyone knows now,

the EU is not a democracy.

Guess what? The Russians don't want NATO bases on their doorstep, just as the US doesn't want foreign military bases in Cuba, sounds familiar?

It was a coup d'etat, noo doubt about it ! People vote for whoever they want, and their vote is the ultimate proof of democracy.

How dare some corrupt official to cancel the will of the people ??