Research suggests that institutional trust increases in times of political crises. Christof Nägel, Amy Nivette and Christian Czymara test this notion for jihadist terror attacks in Europe. Their results imply that political leaders should not take these dynamics for granted

On 10 September 2001, approval ratings for then-US President George W. Bush stood at a lukewarm 51%. This reflected a gradual decline in support since the contentious, closely contested 2000 election. But the American public's scepticism ended abruptly the very next day, when two planes hit New York's World Trade Center. By 15 September, Bush's approval rating had risen 34% points, to 85%. One week later, approval for Bush stood at 90%; the highest rating ever achieved by an American president.

Political scientists call this phenomenon the rally-round-the-flag effect – and it isn't hard to find more recent examples. As the pandemic unfolded in 2020, trust in political administrations increased. Similarly, after Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, support for President Zelenskiy rose sharply. In times of peril, citizens are quick to overlook their earlier concerns about political leaders' shortcomings.

Our research set out to discover whether public trust in political leaders increases in times of crisis, such as in the aftermath of a terrorist attack

But does every terror attack, every pandemic, and every war generate a similar political dynamic? This is an important question for policymakers because, in democracies at least, political administrations depend on public approval. Our research analysed the result of jihadist terror attacks on trust in political leaders.

How do we know whether or not an event changes public attitudes? Recent advances in political science methodology suggest that we can exploit representative surveys whose fieldwork period overlaps with unexpected high-profile events, to study how these events shape public opinion.

One problem is that we are limited to those instances in which terrorist attacks occurred during the fieldwork period of representative surveys. We can, for example, study how the Charlie Hebdo attack changed institutional trust in France because the attack happened during the fieldwork of the European Social Survey. However, we do not know whether the 2016 Nice truck attack had similar effects.

Researchers and policymakers alike must be aware that these 'natural experiments' are merely case studies of one particular moment in time. They do not necessarily translate to other contexts. Our forthcoming study in the European Journal of Political Research considers all possible case studies together.

We systematically searched for every single jihadist terror attack in a European country with at least one civil fatality that occurred during the survey period of the European Social Survey

We could have chosen one particular attack that might have shaped political opinions in one instance. Instead, we systematically searched for every single jihadist terror attack in a European country with at least one civil fatality that occurred during the survey period of the European Social Survey. Similar to other fields, like epidemiology, we treated each attack as an individual case study, and pooled the findings in a meta-analysis. In simple terms, a meta-analysis is a way of combining information from multiple scientific studies to get a clearer picture of a particular topic.

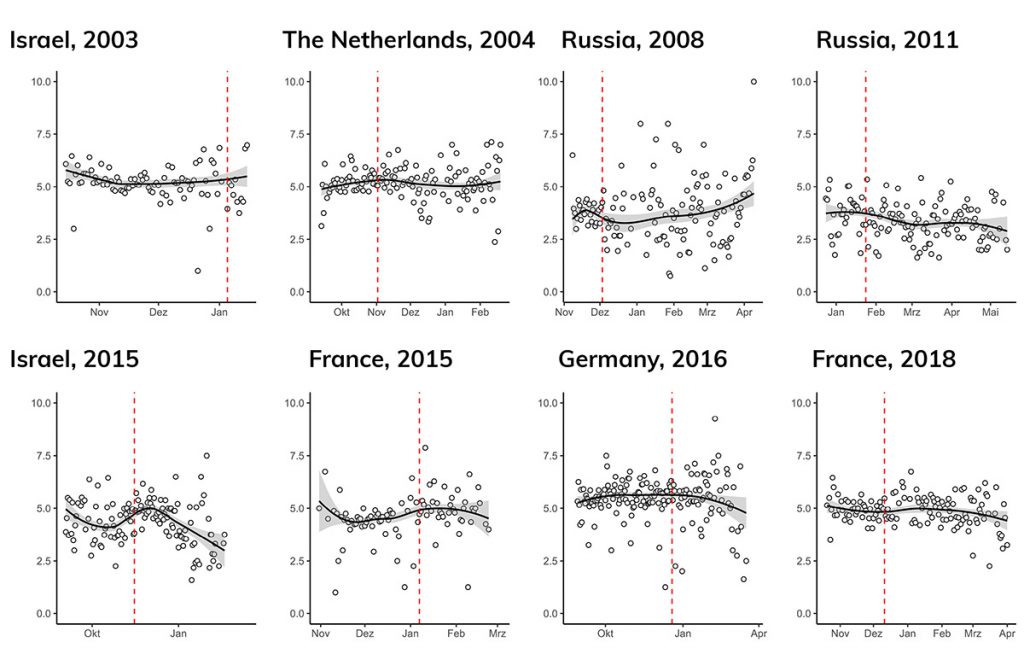

We conducted every single test recommended in the literature to find a robust answer to our research question. However, a simple before/after comparison of institutional trust, as in the graphs below, already helps summarise our results.

10 indicates maximum trust in political and legal institutions

0 indicates no trust in political and legal institutions

The graphs measure institutional trust over the survey period – and before and after each jihadist attack marked by the dotted red lines. It is clear that there is little consistent change in trust following each attack. We can see slight, temporary upticks in the Netherlands in 2004 (the murder of Theo van Gogh), the 2015 Charlie Hebdo massacre in France, and an attack in Israel 2012 in which a Hamas member killed three civilians. However, in other cases, trust remains quite stable, or even substantially decreases, as was the case after the 2011 Moscow airport bombing.

Of course, all these cases are not comparable even if we try to hold as many factors constant as possible. The Charlie Hebdo attack led to the unprecedented Je suis Charlie movement. By contrast, other attacks, such as the one in Russia in 2008, almost didn’t make international news. But even major incidents like the Berlin Christmas market attack in 2016, a similar Christmas market attack in Strasbourg in 2018, or the Tel Aviv suicide bombing that killed 22 civilians in 2003, barely had any measurable effects on institutional trust.

If we follow the state-of-the-art of quasi-experimental research and meta-analyses, our comparative results all point in one direction: the political effects of terrorist attacks do not travel easily from one idiosyncratic context to another.

Following the diversionary theory of war, unpopular leaders can exploit crises such as the threat of terrorists from abroad to divert the public's attention from dissatisfaction with their rule. They can use such crises to strengthen their political prowess through the rally effect, and enforce policies which might provoke considerable pushback under more ordinary circumstances.

Unpopular leaders can exploit crises to enforce policies which might provoke considerable pushback under more ordinary circumstances

So, while the American public grappled with the enormity of 9/11, and support for George W. Bush skyrocketed, the 'War on Terror' was about to unfold. Estimates for the total death toll in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan range from 500,000 to one million.

Our study offers limited evidence that people consistently rally around political leaders and administrations in the wake of jihadist terrorist attacks. Enforcing questionable policies might therefore meet with public backlash in these circumstances after all.

Just like researchers, policymakers should not take rally-effects for granted. The public, on the other hand, should be wary that security crises are ripe for political exploitation.