Unlike most other countries – and flying in the face of ‘securitisation theory’ – Sweden adopted a ‘soft’ approach to managing the coronavirus pandemic. Oscar Larsson considers whether it will succeed

Sweden is often seen as an outlier in its approach to the ongoing global pandemic. It appears reasonably liberal in its attempt to flatten the curve and regulate the circulation of people, and the virus.

During the first wave between March and August, the Swedish government never ordered a lockdown of individual movement and entrepreneurial practices. Instead, authorities communicated a wide range of 'recommendations' as to how people should behave, and pleaded that individuals take personal responsibility for their own behaviour as well as for the general spread of Covid-19.

authorities pleaded that individuals take personal responsibility for their own behaviour as well as for the general spread of Covid-19

At first glance it is a puzzle why Sweden, normally considered a strong state, took such a soft approach, nudging rather than ordering people to alter their behaviour in the face of a large-scale security threat.

'Securitisation' theory is useful to understanding the Swedish coronavirus strategy. The theory suggests that security threats relate to survival (of ‘objects’ of some sort) and that the threat is articulated verbally by someone to an audience (eg the public) who accept what is stated. In an urgent situation (in this case, where people are dying), this then makes it possible to adopt exceptional measures that go beyond established constitutional rules and political procedures.

Initially, there is no doubt that the Swedish authorities engaged in precisely such a process. There were daily press conferences from government officials and representatives from the Public Health Agency of Sweden (PHAS) and other key public agencies, a national broadcast by the Prime Minister and several national information campaigns highlighting the serious nature of the pandemic threat.

Yet, very quickly, Sweden developed an approach that has relied more on advice and recommendations than legislation enforced by threats of punishment for misbehaviour. 'Keep your distance' and 'wash your hands' have become mantras of Swedish government officials and PHAS representatives, albeit combined with binding rules.

Sweden has relied more on advice and recommendations than legislation enforced by threats of punishment for misbehaviour

This approach has created a seemingly illogical mix of advice, resulting in misunderstanding and frustration. For example, the government closed colleges and universities during the spring, banned visits to nursing homes and public gatherings of more than 50, but left restaurants and shopping malls open.

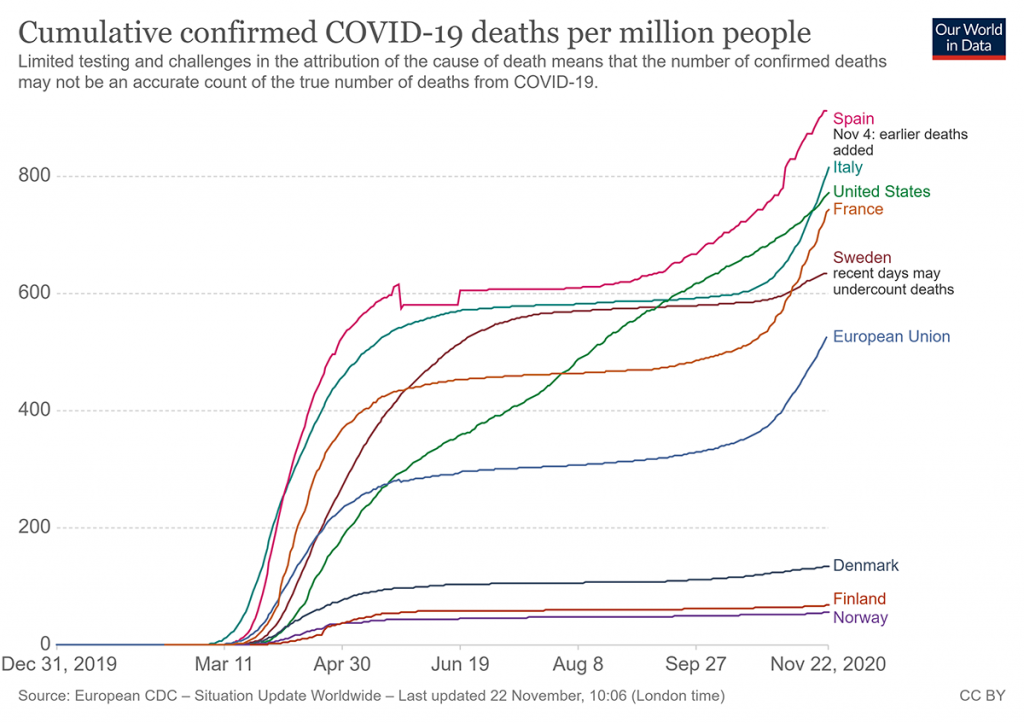

Aside of some new restrictions (public gatherings reduced to eight, no alcohol to be sold after 10pm) the soft approach has continued into winter, despite its evident failure to prevent a second wave. Sweden now has one of the highest death rates in Europe, and indeed the world.

The Swedish model has been criticised for being too feeble and overlooking individual deaths. The question, therefore, is why did Sweden take this soft approach rather than enforcing substantial, exceptional regulation?

Several features of Swedish politics, approaches to crisis management and civil society explain its soft approach. Sweden has a parliamentary system with, currently, a minority coalition government. This makes exceptional governance difficult, although not impossible. The country has no constitutional regulation for managing a civil national crisis or large-scale emergency. In fact, short of a declaration of war, it has no legal provision to declare a state of emergency and implement exceptional measures.

except by a declaration of war, Sweden has no legal provision to declare a ‘state of emergency’

Sweden has a bureaucratic tradition and constitutional arrangements in which the government exercises limited control over public agencies, including the lower administrative levels of regions and municipalities. It also has a decentralised crisis management system which acts on the principles of ‘Responsibility, Similarity, and Subsidiarity’. This means that the practice of ‘ordinary’ governance should prevail as long as possible when coping with a large-scale crisis. So the Swedish crisis-management system is not easy to initiate, control or coordinate.

Finally, Sweden has promoted individual responsibility as a central part of its current crisis-management system, which derives partly from an approach that combines resilience and neoliberalism.

The Swedish coronavirus strategy has attracted a global interest as a different, if not unique approach to managing a pandemic. Many other countries have seen politicians take the lead, enforcing strict and decisive measures and demonstrating strong leadership through difficult times.

Sweden, on the other hand, has relied on PHAS experts, with state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell emerging as a leading figure behind its moderate approach. The WHO has praised the moderate Swedish strategy as a potentially effective strategy for the long term.

But many people, especially within Sweden, are less convinced of its likely success. It is neither a strategy of thoughtful design nor a large-scale social experiment aiming for herd immunity. Rather, it is a patchwork of policy tools in a political and bureaucratic system not really designed for dealing with national crises or threats to security.

It is neither a strategy of thoughtful design nor a large-scale social experiment aiming for herd immunity

Still, the Swedish pandemic strategy raises important normative questions about the management of security that run counter to the influential theory of securitisation, and the possibility that democratic states might be unwilling to break constitutional rules and political procedures to deal with security issues.

Successful or not, Sweden is a case study of authorities sticking with existing modes of government and rules in the face of a large-scale, ongoing security threat.