Europe’s capitals are the largest recipients of refugees because of their infrastructures, existing high proportion of foreigners, and residents’ liberal outlooks. Yet, argues Ilona Lahdelma, rural areas suffering from population shortage might be better equipped to integrate refugees than previously thought. Indeed, both parties might benefit from the arrangement

In 2016, unusual developments in the Finnish town of Kyyjärvi, population 1300, drew considerable media attention. Back in 2015, the refugee crisis had brought a busload of Afghani asylum seekers into this small municipality in Central Finland. The area had no previous experience of managing refugees, and barely any experience coexisting with foreigners. Resistance to the new arrivals was fierce. The municipality's citizens protested vocally against what they saw as an intrusion into their quiet country lives.

However, in just a couple of weeks, local public opinion had transformed. Moreover, when it came time, the following summer, to close the ad hoc reception centre, locals started a successful appeal to keep the reception centre open.

Coming into contact with refugees, rather than just reading and hearing about them in the media, can create very different (and more positive) impressions

What accounts for such a change in public opinion? Part of the explanation lies in contact theory. Coming into contact with refugees, rather than just reading and hearing about them in the media, can create very different (and more positive) impressions. No doubt events like the local multicultural food festival also helped to ease tension between locals and the newcomers.

However, in addition to contact, something else was also happening. Like many rural areas in Western Europe, Kyyjärvi's economy had been suffering from an exodus of working-age citizens. Indeed, labour shortages at the largest local employer, a cement factory, were already causing disruption. Working-age asylum seekers took on jobs at the factory while awaiting their asylum decisions. Forming friendship bonds at work eased the newcomers' integration into Finnish culture. It also provided a welcome boost for the local economy.

I set out to test whether the above story was more than just a feel-good anecdote. After all, many Western European regions are suffering from systematic depopulation. When young people move out, there is nobody to subsidise and care for the ageing population. The fewer people live in a municipality, the less tax income is generated. This, in turn, means less justification for continuing local services such as a post office, school, or health clinic. Do people in rural areas understand the potential economic benefits asylum seekers can bring?

When working-age people move out, less tax income is generated, and this means less justification for continuing local services

To find out, I gathered information about Finnish politicians’ pre-election policy pledges in 2012 and 2017. In both those years, the Finnish Voting Advice Application system asked politicians hoping to get elected to municipal councils about their support for accepting refugees in their localities. I created a treatment group that received asylum seekers in their municipality and a control group that did not. Municipalities that were otherwise very similar either received or did not receive asylum seekers based on the government’s impromptu need to open reception centres wherever they found a suitable building. I then matched these responses with the candidate’s vote share and the municipality’s socio-economic characteristics.

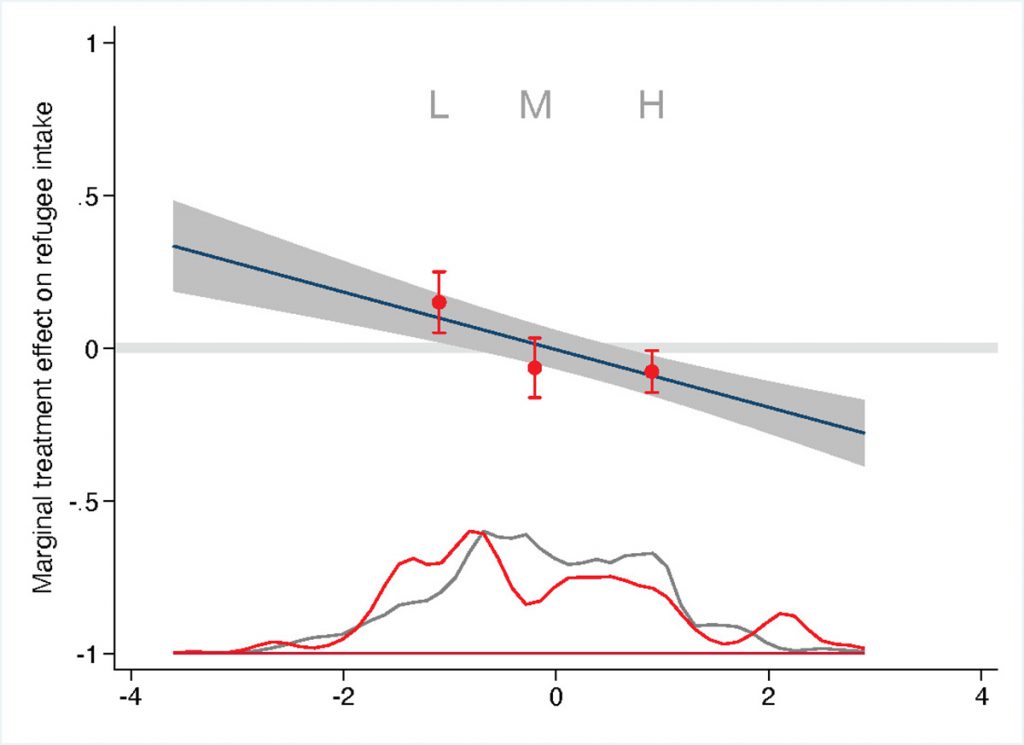

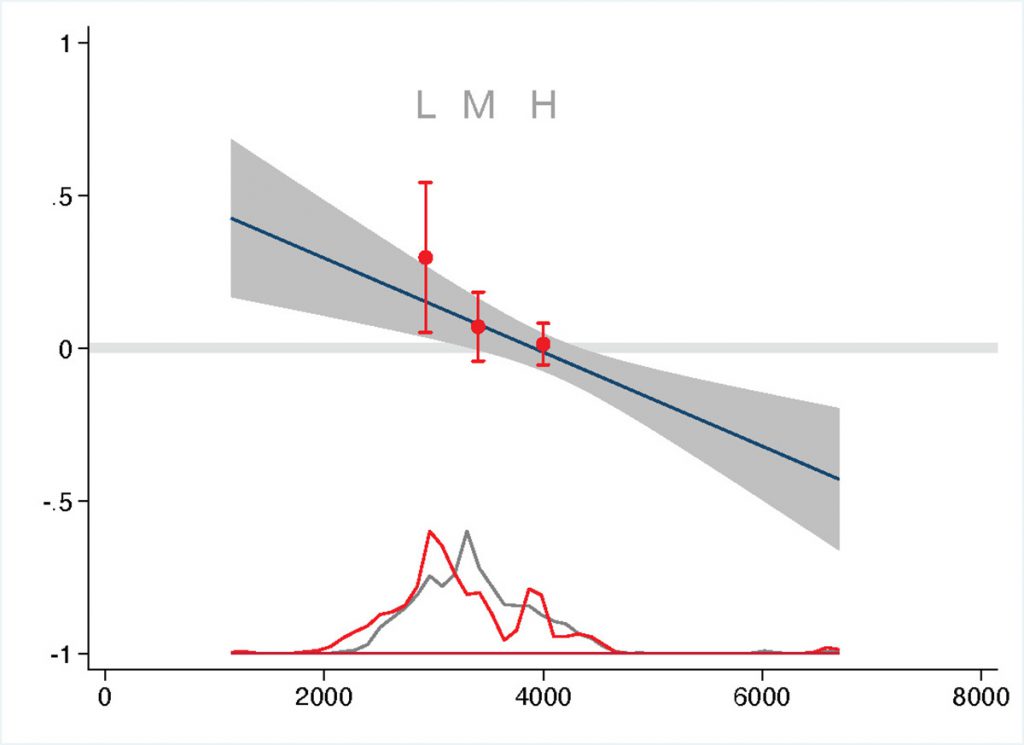

The first striking finding was that the higher the per-capita number of asylum seekers in a municipality, the more local politicians had changed their stance between 2012 and 2017 in favour of asylum seekers. In practice, this means that smaller municipalities reacted more favourably to asylum seekers than cities, when compared to their previous levels of acceptance.

Next, I explored to what extent the socio-economic characteristics of the municipality explain the results. I found a very clear and consistent pattern. The more rural a municipality, and the more it was suffering depopulation and demographic challenges, the more the change of opinion was favourable towards refugees upon hosting them.

I also analysed politicians’ open-ended comments regarding the matter. This analysis, too, confirmed the same pattern. In rural areas, politicians saw refugee intake as a means to address depopulation and create economic growth in the municipality. In cities, meanwhile, politicians saw it as a humanitarian expense.

rural municipalities with experience of asylum seekers were more likely to opt in to refugee integration schemes than urban or rural municipalities without experience of hosting migrants

Finally, I was able to observe the political repercussions of these shifts. Refugee-supporting politicians did not suffer any electoral backlash in rural municipalities. They also implemented their political promises: rural municipalities with experience of asylum seekers were more likely to opt in to refugee integration schemes than urban or rural municipalities without experience of asylum seekers.

Anecdotes and feel-good media stories of asylum seekers and locals befriending each other have popped up around Europe, in Scotland, Ireland, Germany, and Austria. However, outside of Finland, there is scarce micro-level data about policy opinions. It has therefore been difficult to determine causality, or to establish the policy implications of such stories.

However, recent studies such as those by Steinmayr and by Vertier, Viscanic and Gamalerio suggest that smaller localities in France and Austria show a positive reaction to asylum seekers when the impact is measured as a decrease in local votes for the far right.

To what extent the effect stems from contact and to what extent it stems from economic benefits remains unclear. However, irrespective of the factors at work, it seems that the arrival of refugees does activate positive mechanisms in rural areas. It might be time to start exploring the feasibility and potential benefits of placing refugees in Western Europe's rural municipalities. Doing so could be a win-win situation for newcomers and locals alike.