Increasing inequality does not always result in governments increasing redistribution, even when the public is in favour of it. To understand this puzzle, Cristian Márquez Romo and Hugo Marcos-Marné examine the preferences of the governmental elites implementing public policy

The Romer-Meltzer-Richard (RMR) model posits that income inequality promotes redistribution via voter preferences. Building upon this theory, a longstanding debate in political economy examines whether higher economic inequality does indeed strengthen governmental income redistribution. While some studies support this hypothesis, the evidence remains far from unanimous. Recent efforts to clarify this association examine comparative evidence over a longer timeframe. This helps address technical challenges such as controlling for unobserved heterogeneity and country-specific secular trends.

Our study contributes to this discussion by focusing not on the redistributive preferences of citizens or economic elites, but on those of policy-makers. Testing the RMR model among political elites is particularly relevant because it is Members of Parliament who translate public preferences into policy actions.

To find out whether inequality promotes redistribution, we examined the preferences of the elites who translate public preferences into policy

In fact, the RMR model outlines a three-step process that helps clarify the relationship between income inequality and redistribution. First, it predicts that public demand for redistribution will rise as inequality increases. Second, it anticipates that growing demands for redistribution will result in more votes for political elites and parties that endorse redistributive policies. Finally, it holds that incumbent parties will, in turn, implement these redistributive policies.

Most research has focused on the first step of the argument – whether public demand for redistribution increases as inequality rises. But it is essential to assess whether this demand ultimately translates into votes and redistributive policies. Indeed, growing evidence suggests that changes in inequality drive support for redistribution in 27 European countries, a sample of 32 Western countries, and 18 Latin American countries. Future research should therefore focus more on propositions two and three of the RMR model.

Responding to these findings, our study examines the relationship between economic inequality and redistribution preferences by leveraging comparative elite-level survey data from more than 2,300 MPs in 18 Latin American countries. To assess changes in elites’ redistributive preferences, we analysed pooled cross-sections of surveys, collected from 2010–2018. During periods of rising inequality and increasing public consensus for greater redistribution, are democratic governments capable and, most importantly for us, willing to translate these preferences into actual policy?

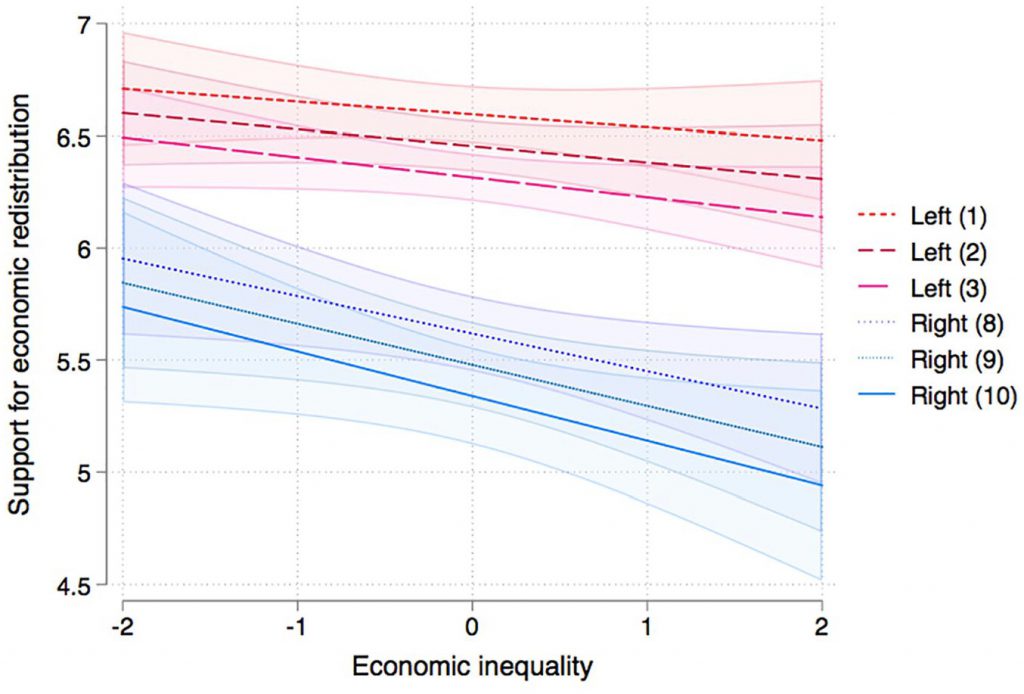

We can summarise our findings in two key points. First, we find a negative and consistent over-time association between inequality and support for redistribution. This holds constant even after we control for legislators’ self-positioning in the left–right scale. As we expected, right-wing MPs are less likely to support redistribution in contexts of higher economic inequality. However, we also uncover counterintuitive evidence of a similar, albeit weaker, pattern among left-leaning legislators.

When inequality runs higher, Latin American legislators are less likely to endorse State intervention to reduce it

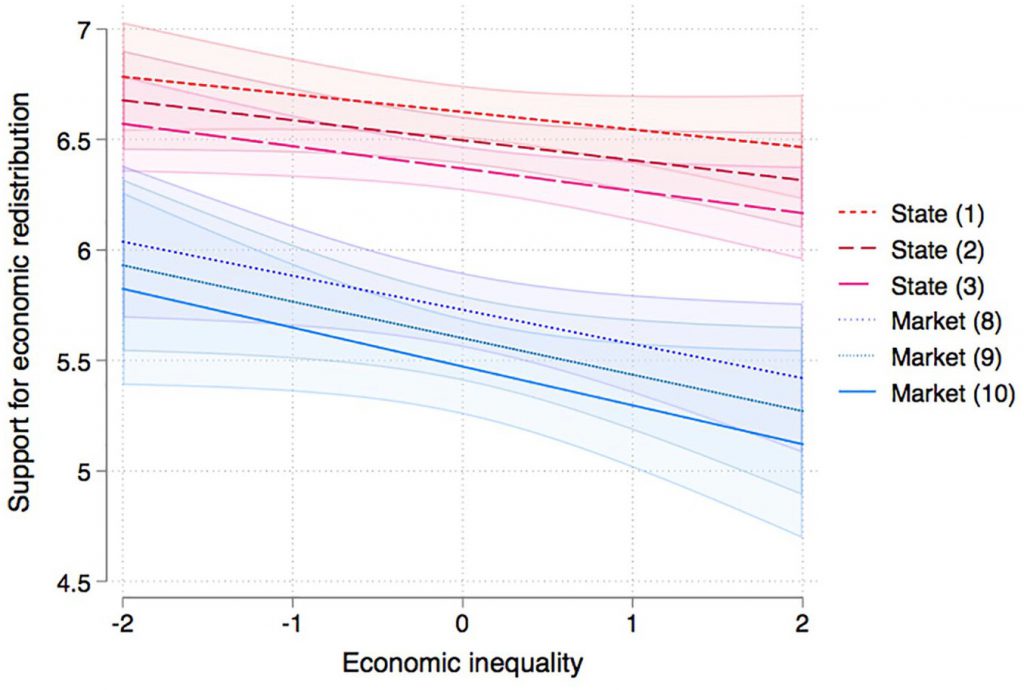

To assess the robustness of these results, we also used a more direct measure of MPs’ preferences about the intervention of the State in the economy. Analyses based on both operationalisations yield the same conclusion: during periods of higher economic inequality, Latin American legislators are less likely to endorse State intervention to reduce it. While the effect is particularly pronounced among right-wing and pro-market legislators, it remains consistent among ideological groups.

A number of factors, we speculate, are contributing to this negative effect across ideological groups. One is the enduring influence of the neoliberal paradigm across Latin America. Another is the capture of democratic institutions by economic elites, which makes political elites more prone to mirror the interests of the former. Finally, there is MPs’ awareness of the political conflict that redistributive social policies may trigger among powerful insider groups.

Stark inequality concentrates political power, making it even harder to tackle the inequality trap

Regardless of the specific mechanism, our findings suggest there is indeed an ‘inequality trap’. High inequality concentrates political power, making inequality even tougher to address. In fact, consistent with our findings, some studies had already shown that higher inequality tends to widen the redistributive preference gap between political elites and the general public.

Empirical evidence for the full causal chain proposed by the RMR model offers valuable insight into the cycles and persistence of inequality in Latin America – one of the most unequal regions in the world. A recent report based on the Latin American and Caribbean Inequality Review reveals how inequality is reproduced across very different aspects of life. Indeed, inequality has persisted despite important structural and socioeconomic changes in the region. These cycles reinforce an enduring divide between a struggling majority and a small elite that continues to accumulate disproportionate gains.

In 1959, Martin Lipset argued that a society's distribution of economic resources influences its likelihood of maintaining a thriving democracy. Building on the accumulated evidence supporting his theory, a growing body of research suggests that persistently high inequality can be a long-term driver of democratic erosion, because it fosters socially immobile, violent, and polarised societies.

Our study suggests that in countries with stark inequality, MPs’ reluctance to pursue redistributive policies can be influenced not only by external pressures such as the technical complexities of implementing these programmes, or the influence of more affluent individuals seeking to obstruct them, but by shifts in their own attitudes toward redistribution.