Four recent cyber catastrophes might look like an uptick in activity, but what they really prove, argues Tom Johansmeyer, is that the economic threat remains manageable. With only $5.7 billion in economic damage, the latest wave should help alleviate fears that the 'big one' is still around the corner

The tempo of cyber catastrophes has picked up, and still nothing has changed. Four events over the past 16 months show that cyber catastrophe risk remains an ongoing problem. It may even be increasing in frequency. However, the threat they pose appears to be far less than the fear of a cataclysmic cyber attack suggests. The four recent cyber catastrophes demonstrate that the economic effects of cyber catastrophes are completely manageable.

The word 'catastrophe' feels loaded, but it has a job to do. In insurance industry, a 'catastrophe' is a major event that has broad reach. For an event to be a catastrophe, in the United States and elsewhere, it needs to meet a threshold for insured loss (in the US, $25 million) and affect a 'significant number of insurers and insureds'.

We can easily transfer this concept to the cyber domain. It can be useful in the cyber security and policy world, too, offering succinct and effective categorisation for major cyber attacks that have broad effect. To adapt the concept from the insurance industry, though, I’ve taken the 'significant number' standard above and applied it to victims broadly. This differentiates a cyber catastrophe like Crowdstrike or WannaCry from an extremely costly cyber attack with only one or a limited amount of victims, like Equifax.

Using an economic loss threshold of $800 million, we can see that cyber catastrophes are becoming smaller, but seemingly more frequent

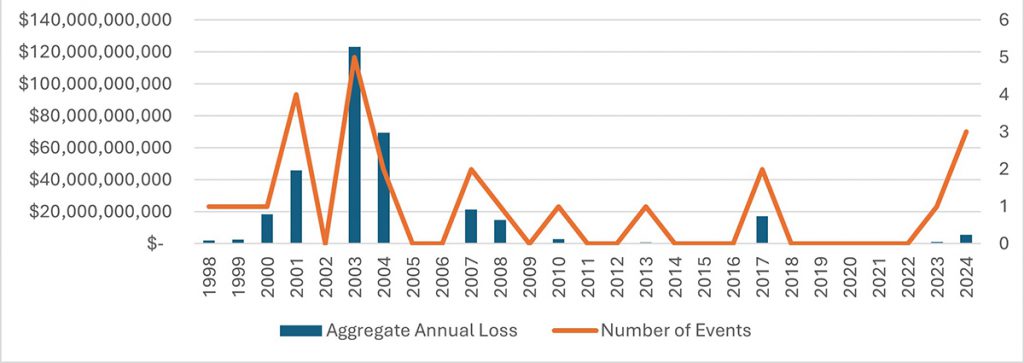

The use of an economic loss threshold of $800 million, as I have previously discussed in The Loop, is to balance scale of loss with the opportunity to collect as much relevant data as possible. It has also helped reveal a new and emerging trend. Cyber catastrophes have become smaller, but seemingly more frequent.

Since May 2023, four events have occurred that meet the cyber catastrophe definition above: MOVEit, Change Healthcare, CDK, and Crowdstrike. The first three were cyber attacks; Crowdstrike involved a system error. Although the cause was different, from the standpoint of economic effect, we can usefully analyse all four together. The four events caused an estimated $810 billion in aggregate economic losses. As with past estimates, these estimates are generally based on publicly available information. Private interviews with key experts (in the insurance industry) also informed the MOVEit estimate.

The most recent event, Crowdstrike, has two publicly available economic loss estimates, both from cyber risk quantification and analytics firms. Parametrix puts the loss at $5.4 billion. Cyence estimates it at $1–$3 billion, with a 'best estimate' of $1.7 billion. The latter is more realistic, as the former implies an event larger and more economically impactful than WannaCry (adjusted for inflation). Additionally, conversations I’ve had with insurers suggest that the economic losses were not far above those insured. The visuals from the Crowdstrike event were stunning but not suggestive of genuine economic loss.

Together, the four recent cyber catastrophes caused an estimated $8–$10 billion in aggregate economic losses

The CDK estimate, which affected auto dealers across the United States, was also approximately $2 billion. This estimate is according to limited publicly available data and I have cross-checked it with insurance industry intelligence. Change Healthcare was about the same.

That leaves MOVEit, for which there is one publicly available source estimating more than $9 billion. Analysts have made flawed assumptions about the scale of loss based on a cost-per-record metric associated with the privacy implications of the event. The following two victims illustrate the point.

Wilton Re, a reinsurance company, would have an estimated economic impact of approximately $200 million. This number is equivalent to nearly 80% of its 2023 life and health premium (colloquially, revenue). Such an impact would have been noteworthy for a relatively small company, which hasn’t had any announcements suggesting cataclysmic effect. Nuance’s $200 million would have been more than twice the size of its economic loss from NotPetya ($90 million, not adjusted for inflation). However, there have been no announcements, and no estimates have been revealed.

Through private conversations with insurance industry executives, I’ve learned that an economic loss estimate of $1 billion is more realistic for MOVEit. They indicate that the loss was relatively contained. The difference between insured and economic losses, based on reports from their clients, was not significant.

The four events bring the total aggregate economic loss from cyber catastrophes from 1998–2024 to $326.4 billion, which includes an adjustment of past events up to 2024 at the same 3% annual rate of inflation used in previous analyses. It further includes an aggregate $5.7 billion from the four events above. The average economic loss per event 1998–2024 falls to $13.1 billion from $14.8 billion in my last analysis, showing that, even as events have become more frequent, the drop in severity is hard to ignore.

The economic losses from the four most recent cyber catastrophes provide important framing for the problem of economic security regarding major cyber events. The uptick in frequency does suggest the potential for greater impacts than single-victim attacks, which is an important development that can shape cyber security strategy. However, it also suggests that increasing cases of widespread (to an extent) impacts are utterly absorbable economically. The economic implications of cyber catastrophe remain completely manageable, and that presents an opportunity.

Instead of preparing for a Hollywood-style cyber calamity, it makes more sense to learn how to manage smaller-scale economic risk

Instead of preparing for a Hollywood-style cyber calamity, it makes more sense to learn how to manage smaller-scale economic risk. This requires a shift in mindset from preparations for conflict and major state-actor operations to more mundane matters, such as cyber insurance. The increase in small catastrophes is useful because it gives us more data to analyse. And we can either use the data in front of us, or wait for the types of events we fear – even if those fears are not justified.