Paul Biya, the world’s oldest head of state and the second-longest ruling leader in Africa, ran for a record eighth term earlier this month. John Chin and Julien Derroitte assess Cameroon’s prospects for peace and democracy in Africa’s turbulent coup belt

On Sunday 12 October, Cameroon became the sixth of ten African states in 2025 to hold executive elections. With the main opposition candidate barred from running and civic space restricted, most expected 92-year-old Paul Biya to win an eighth term to extend his 43-year rule, despite rumours of failing health, his daughter's public defection, backlash to an AI-generated campaign video, and a crisis of terrorist violence.

Though official results are not expected to be released until between October 23 and October 27, the outcome has already been contested. On 13 October, Issa Tchiroma Bakary – former Biya ally and long-time cabinet minister turned challenger – declared victory. But provisional results published on 21 October gave Biya a victory, with 53% of the vote to Tchiroma's 35%. On 22 October Cameroon's top court rejected election petitions.

If the Constitutional Council – packed with ruling party loyalists – declares Biya the winner, this could trigger unrest and, eventually, a coup. Bakary has already called for more opposition protests if Biya is declared the winner, and has turned down Biya's offer to serve as prime minister.

Former Biya ally turned opposition challenger Issa Tchiroma Bakary declared election victory on 13 October, but the Constitutional Council could still declare Biya the winner

A desire for change and democracy is building; the Catholic Church has urged Biya to step down and permit democratic transition. An opposition alliance, the Union for Change, backed Tchiroma’s candidacy. Frustration is mounting over corruption, poverty, and youth unemployment, especially among Cameroonians under 25 who constitute 60% of the population. Trust in political institutions is declining. According to Afrobarometer, only 47% of Cameroonians trusted the president in 2024, down from 55% in 2023. Only 27% expressed trust in the ruling party.

Cameroon’s era of ‘boring’ stability is likely drawing to a close. Unlike dictators in Chad or Togo, Biya has not groomed his son Franck for dynastic succession. Cameroon risks becoming another domino in the Sahel’s expanding belt of instability.

Strongmen have long dominated Cameroon’s politics. First was Ahmadou Ahidjo until his retirement in 1982, and then Paul Biya, who has ruled since 1982. Whereas Ahidjo favoured northern Muslims, Biya replaced key Muslim officials with Christians. After discovering an alleged coup plot in 1983, Biya forced Ahidjo into exile. Ethnic narrowing and high-level purges contributed to the only coup attempt in Cameroon’s history, in 1984. Biya consolidated his own personalist regime by coup-proofing – recruiting co-ethnic Betis from the south into the security forces and taking leadership over a new ruling party, the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement.

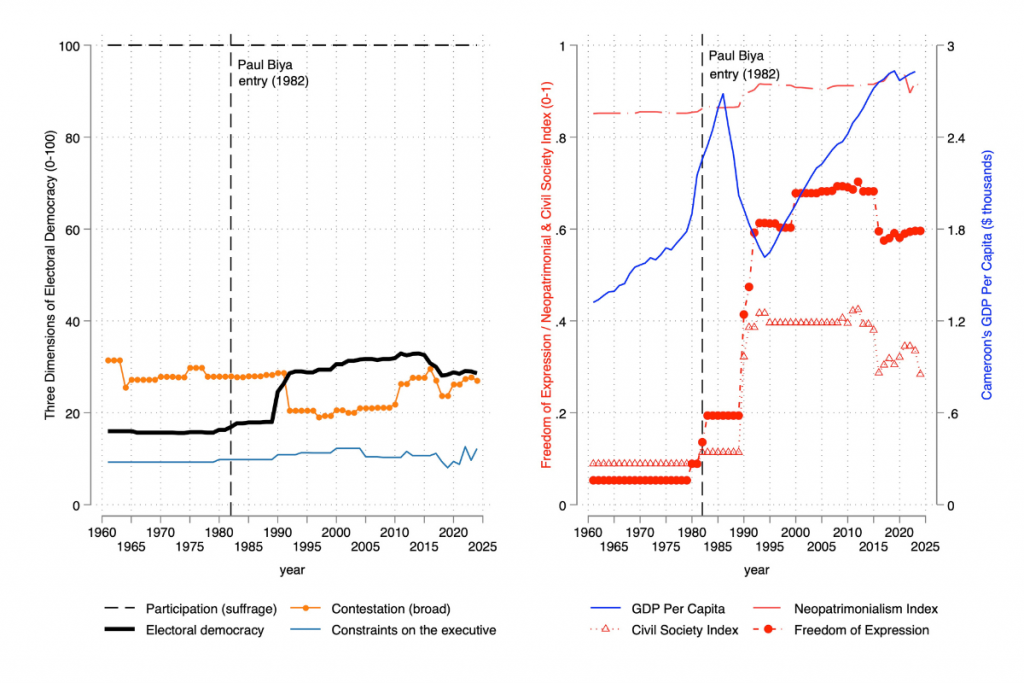

Multiparty elections were introduced in 1992, but Cameroon remained an electoral autocracy. With the opposition fragmented and loyalty of the security forces secured, Biya won re-election in 1992 with just 40% of the vote. For the next two decades or so, Cameroonians benefitted from greater levels of freedom of expression and civil society openness (per V-Dem data) as well as stronger human rights protections.

After Biya's win in 1992, Cameroonians benefitted from stronger human rights protections for two decades, but after Biya won again in 2011, Cameroon became more repressive and civil liberties less respected

However, after a 2008 constitutional amendment abolished term limits and Biya won elections in 2011, the country became more repressive and civil liberties less respected. A Rapid Intervention Brigade established by Biya in 2001 has been accused of abuses. Despite allowing political participation, the Biya regime has always benefited from a lack of electoral contestation and few constraints on the executive:

Press freedom, too, has suffered since the introduction of an anti-terrorism law in 2014. By 2025, the average Cameroonian was no more wealthy than in 1986; four in ten Cameroonians live in poverty.

In 2024, Cameroon re-entered the global top ten countries most afflicted by terrorism, stemming from two internal armed conflicts with different groups in different regions. As a result, Cameroon suffers the world’s most neglected displacement crisis, with a million internally displaced people and another half million refugees and asylum seekers.

Cameroon is in the global top ten countries most afflicted by terrorism. Two internal armed conflicts have left a million people without homes

Cameroon’s long-running anglophone crisis – pitting a minority English-speaking population in the west against the majority Francophone-dominated government – escalated into armed conflict in 2017. After a violent 2016 government crackdown on anglophones, 'Ambazonia' separatist militants demanded independence and took up arms. The conflict affects some five million anglophones; it has killed more than 6,000 people.

Meanwhile, Islamist violence has only escalated since 2014, when rival Boko Haram splinter groups – the Jama’tu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (and the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) – launched an insurgency inside Cameroon with thousands of fighters. Though ISWAP violence fell in 2024, Boko Haram ramped up border attacks in the far north, which saw Islamist violence increase 51% in 2024.

Cameroon contributes to the Multinational Joint Task Force combating Boko Haram, but it lacks troops, equipment, and coordination needed for successful counter-insurgency. Despite the 2014 anti-terror law that has suppressed political opposition, the state is increasingly unable to protect civilians. Thus, many in the most dangerous regions have joined vigilante groups like the Civilian Joint Task Force in Nigeria.

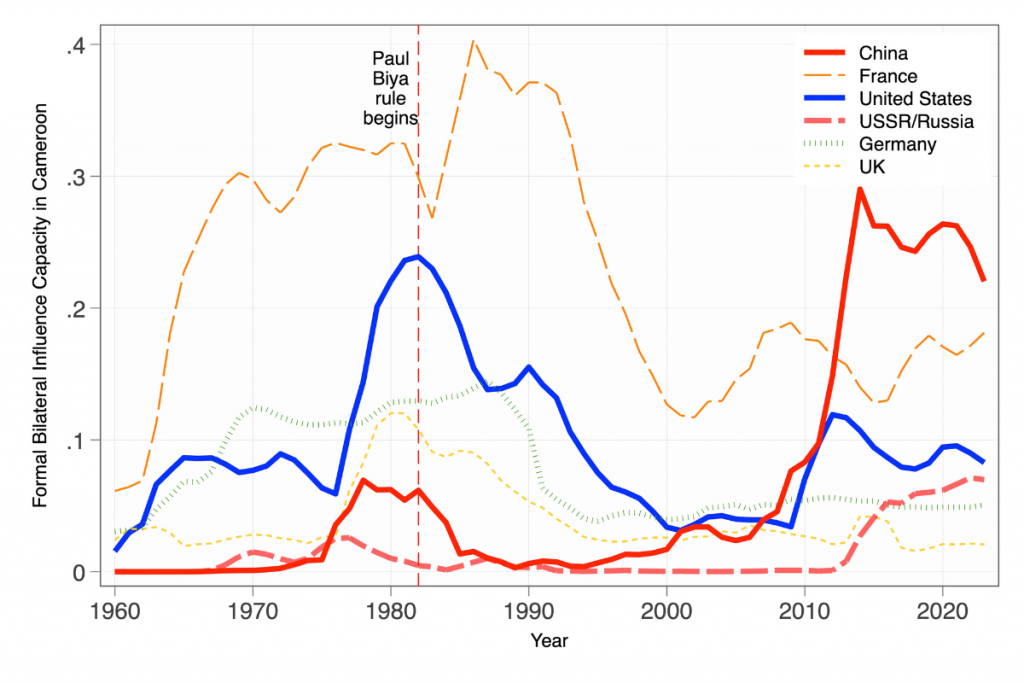

Whereas the Ahidjo regime was dependent on France, over time Biya diversified international partnerships and sought good relations with all major powers. As a result, western influence capacity in Cameroon has declined, whereas that of China and, to a lesser extent, Russia has greatly expanded in the last ten to fifteen years, per FBIC data:

In 2024, Biya visited Beijing for the eighth time and Cameroon and China bilaterally upgraded to a 'comprehensive strategic partnership'. Cameroon joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2015, which led to rising Chinese infrastructure investment in Cameroon. As a result, China owns 66% of the new strategic port at Kribi. Last year, China overtook France to become Cameroon’s second-largest export market.

Russia and Cameroon have also strengthened military cooperation over the last decade. The two countries signed military deals in 2015 and 2022. Since the invasion of Ukraine, hundreds of Cameroonian soldiers have deserted to fight for Russia in Ukraine, drawn by the pay that is some ten times higher than they could earn at home.

In September, US Africom commander General Dagvin Anderson visited Cameroon to underscore US support for counter-terrorism. But Cameroon’s exclusion from the African Growth and Opportunity Act since 2020, and the Trump administration’s recent cuts in US foreign aid, make it harder to craft or execute a workable strategy to combat rising sharp power in Cameroon at a critical time.

In Africa do it a re electing a Cameroons forever presidents that will do it grow the Africa country rapidly.