On 1 January, Poland took over the rotating EU presidency from Hungary. John Chin and Ellie Kim outline the stakes for Europe, and the imperative of promoting a democratic U-turn in central Europe – and Poland itself – after years of democratic backsliding

Warsaw recently took over the presidency of the EU Council from Budapest. This changing of the European guard comes as battle rages over whether conservative populist nationalism or liberal internationalism prevails.

From 2015 to 2023, Poland under the Law and Justice (PiS) party and Hungary under Viktor Orbán were poster children for democratic backsliding in central Europe. But in the 2023 parliamentary elections the PiS lost to a coalition comprising the Civic Coalition, Third Way, and The Left.

Whether Poland under Prime Minister Donald Tusk can rally Europe to defend the liberal international order (and Ukraine) is tied to the outcome of Poland’s presidential elections in May, and the ability of Poland itself to achieve a democratic U-turn.

Poland quickly transitioned to liberal democracy after the end of communist rule, joining NATO in 1999, the EU in 2004, and the Schengen zone in 2007. By 2011, Poland’s democracy appeared consolidated when Tusk’s Civic Platform won an unprecedented second term. In 2012, Poland was hailed for its post-Cold War track record as a democracy promoter. In 2014, Tusk, a pro-European Russia hawk, was elected president of the European Council in what was hailed as a 'big moment for Poland'.

By 2011, Poland's democracy appeared consolidated. Yet in 2015, a cultural backlash helped catapult the anti-EU, anti-immigrant PiS to power

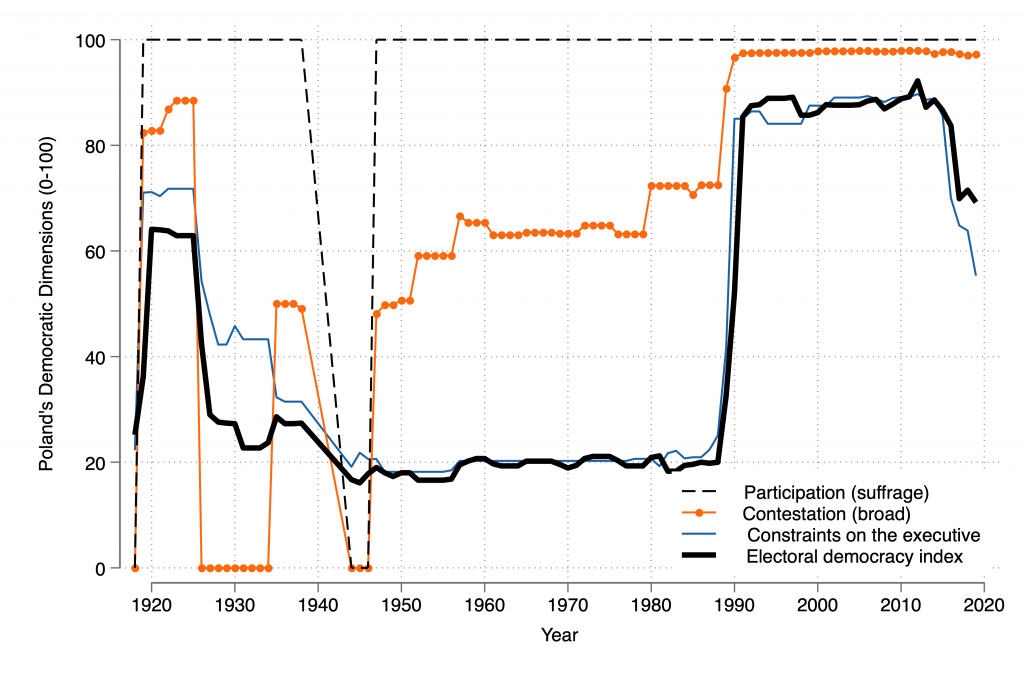

Despite 25 years of economic development, however, a cultural backlash – including latent anti-EU and anti-immigration sentiment among youth and conservative voters in smaller towns and poorer areas (especially the southeast) – helped catapult the PiS to power in 2015. Under PiS rule, Poland suffered the most democratic backsliding of any European country in the decade to 2023, according to V-Dem, which downgraded Poland to an electoral democracy in 2016. By 2018, Poland became the first EU country threatened with sanctions for rule-of-law violations under Article 7 of the Lisbon Treaty. Although declines in media freedom and judicial independence weakened constraints on the PiS executive, electoral participation and contestation remained robust, as the graph below shows:

In Poland, democracy eroded from the top and from the right. Once in office, PiS elites replaced their moderate campaign rhetoric with authoritarian populism, pursued Hungary’s illiberal model of 'sovereign democracy', and spread conspiracy theories (e.g. about the 2010 Smolensk plane crash that killed then-President Lech Kaczyński).

In Poland, democracy eroded from the top and from the right

President Andrzej Duda narrowly won re-election in controversial 2020 elections. Since the PiS lost the 2023 parliamentary elections in which democracy itself was a key issue, President Duda has clashed with Tusk’s government. Poland’s democratic backsliding may have stopped in 2023, but this did not result in an immediate resurgence in democracy.

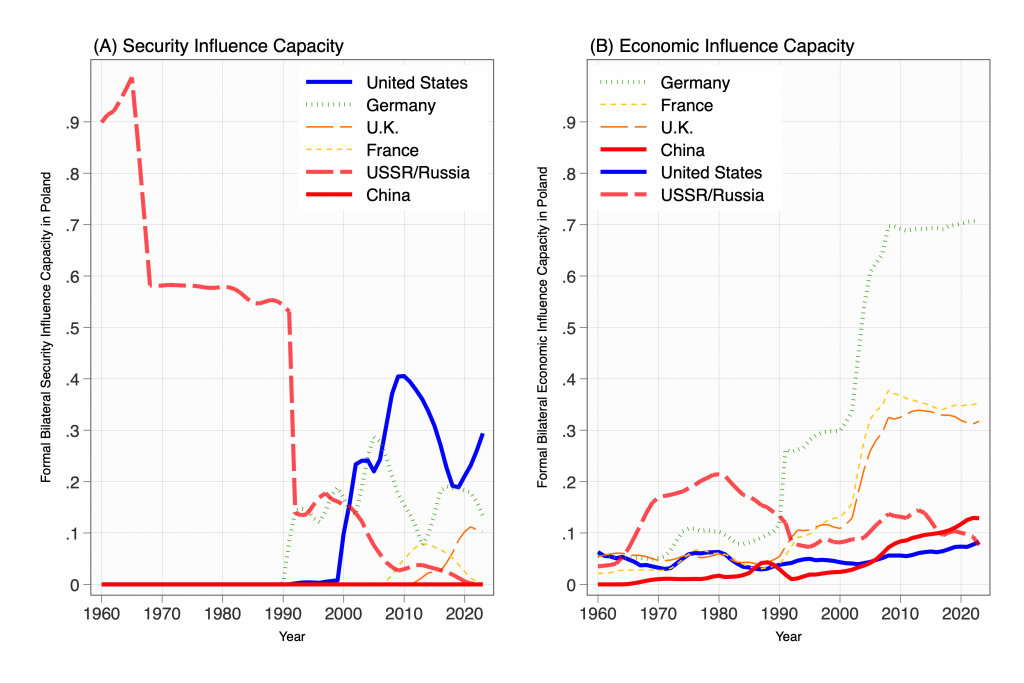

The generation that lived through communist rule in Poland looked to join the West after 1989. As Adam Michnik put it, 'Europe meant freedom, normalcy, economic rationality'. Germany and the United States replaced the Soviets as Poland’s principal post-Cold War security partners. Though China’s economic influence in Poland has gradually grown in recent years, it still lags behind Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, as FBIC data shows:

To counter Western influence, sow discord, and undermine support for democracy and Europe/Ukraine in Poland, Russia has employed sharp power, including propaganda and disinformation spread via social media, sabotage, and even military threats. Last May, Poland accused Russia of meddling in EU elections. Earlier this month, Poland claimed a group linked to Russian military intelligence was spreading disinformation to influence the May presidential elections.

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, according to a 2021 poll, four in ten Poles regarded Russian influence as a threat to their democracy. To counter Russia internationally, between 2014 and 2024 Poland doubled defence spending as a percentage of GDP, and since 2022 has provided Ukraine with significant aid and weapons. Poland backs Donald Trump’s call for NATO countries to boost defence spending to 5% of GDP.

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, four in ten Poles regarded Russian influence as a threat to their democracy

Domestically, President Duda signed a bill in 2023 creating a committee to investigate Russian influence in Polish politics. Critics worried it could provide cover to target opposition. But in 2024 Prime Minister Tusk revived the commission under the chief of military counterintelligence, and announced an additional $26 million for intelligence services to counter Russia. In 2022, Poland ended its gas deal with Russia, and supports a ban on Russian gas exports to Europe. Poland has made resisting foreign interference and disinformation a priority of its 2025 EU presidency.

Once autocratisation begins (as it did in Poland), only one in five democracies manage to avert democratic breakdown. But Poland’s chances of making the U-turn are not hopeless. Poland still has a plural governance system featuring directly elected local governments. Though PiS voters tolerate anti-democratic behaviour and drifted 'toward indifference to democracy', most Poles still express support for democracy. Poland’s youth have more progressive attitudes towards women’s and gay rights, and only 20% support the idea of a strong leader who disregards parliament.

Five common factors are associated with recent democratic U-turns:

Several of these are present in Poland, including heightened mass mobilisation for democracy since 2015, and a unified opposition which contributed to the critical 2023 election. Yet the 2025 presidential election may prove equally critical.

Western actors must do what they can to support Poland’s democratic U-turn. In May 2024, the European Commission ended its Article 7 procedure against Poland. Ensuring follow-through on Poland's commitments to democracy is critical.

If the EU’s future will be decided in central Europe, it is critical that Poland’s 'illiberal detox' succeed.

[…] European Consortium for Political Research detailed how, since 2015, there has been a shift in Poland toward democracy that culminated in the 2023 […]