Donald Trump’s pledges to rename the Gulf of Mexico, to rechristen Mount Denali as Mount McKinley, and to ‘take back’ the Panama Canal, are all intended to evoke America’s imperial past. Bruno Sowden-Carvalho analyses how the emotional appeal of sea power and ontological security sheds light on the political psychology behind Trump’s motivations

Striking features of Donald Trump’s 2025 inaugural speech were his pledge to rename the Gulf of Mexico the ‘Gulf of America’ and to revert to calling Mount Denali Mount McKinley. Trump linked the economic legacy of President William McKinley, who served 1897—1901, to Theodore Roosevelt’s development of the Panama Canal (which Trump also hinted at ‘taking back’).

What does this Gulf of Mexico-McKinley-Panama link reveal about Trump 2.0 and twenty-first century geopolitics? The answer lies in the human psychological drive to feel a stable sense of self, or ontological security, and the emotional appeal of sea power during America’s late nineteenth-century expansion.

Ontological, from the Greek ontos meaning ‘being’, refers to the discourse and practice of ‘being you’. A person is ontologically secure when they feel psychologically whole through a sense of self that separates them from others and the environment. We nurture this feeling through the stories we tell about ourselves, our routines, and the narratives that socially anchor us.

Cognitive psychologists have increasingly suggested this sense of stability is a ‘controlled hallucination’. The human brain constructs reality by generating predictions, and masking changes to maintain coherence. For the sake of allostasis — the regulation of change to ensure the body’s survival — the brain evolved to be change-blind. Most of the time, we do not perceive significant physical or environmental changes. This creates the illusion of continuity and wholeness, which nonetheless is practical and real. The unitary Self is, therefore, an ongoing emotional construct.

Just as individuals sense that their Self is in control, so too do international actors. Not because these actors ‘have’ emotions but, rather, because emotions shape what individuals perceive the state to be, which in turn defines who they are.

When the US Navy names one of its aircraft carriers after a former president, it imbues the machine with emotional charge

For example, when the US names an aircraft carrier after a former president, that imbues the machine with emotional charge. This reinforces the ‘controlled hallucination’ that America(ns) is/are united and whole. Such symbols define what America is, and is not — delineating emotional boundaries between Self and Other.

Political problems arise when such a constructed Self is challenged — as it has been by pandemics, grassroots protests, and shifting global dynamics — generating anxiety, distrust, and fear. So, from the perspective of ontological security, politics is also a contest to determine which emotions matter. While international actors can never be fully ontologically secure, they strive to construct a coherent Self through symbols, narratives, and rituals.

Examining Trump’s inaugural speech through this perspective is revealing — not least because Trump narrowly avoided the fate of President McKinley, who was assassinated in 1901. However, the deeper connection between McKinley’s administration, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Panama Canal lies in the concept of sea power in the American Self.

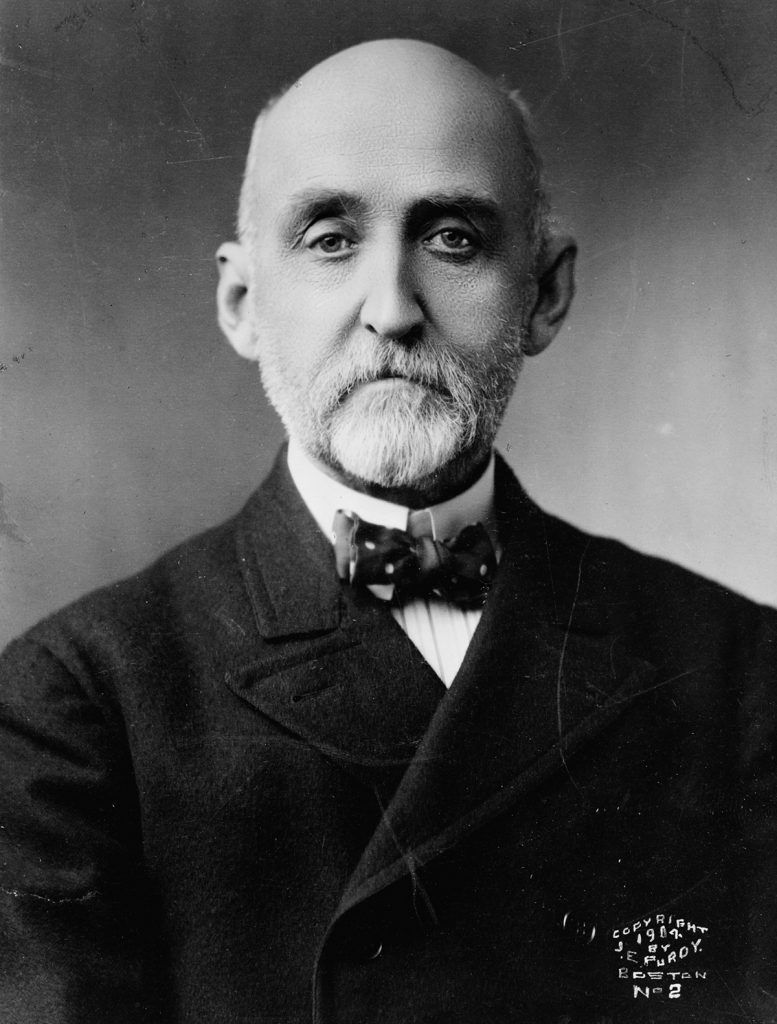

The bestselling 1890 book The Influence of Sea Power upon History by Alfred Thayer Mahan (1660–1783) articulated this concept by identifying its geographical, social, and political elements. Mahan argued that sea power determined the prosperity of nations: those who master its elements with powerful navies can command the seas. Conveniently, he used Britain — leading maritime power of the time — as evidence for this hypothesis.

Mahan’s mission was to galvanise public opinion and policymakers to expand America’s Navy during the uncertain late nineteenth century, when rising powers like Germany, Italy, and Japan, along with colonial competition, were all stoking anxiety. While motivations for naval expansion already existed, Mahan crystallised them into a persuasive narrative that formed the scaffolding for the ontological security the US sought.

Historian Alfred Thayer Mahan crystallised motivations for naval expansion into a persuasive narrative that helped secure US maritime dominance

In an 1897 paper, Mahan's sea power argument highlighted the strategic importance of the Gulf of Mexico. He compared the Caribbean to the Mediterranean, identifying chokepoints such as the Yucatán Channel and Florida Strait as crucial for controlling trade and military movements. He also emphasised Cuba’s geographical position as key to dominating the region. Linking this to the growing interest in an Isthmian canal (later the Panama Canal), Mahan argued that such a canal could secure US maritime dominance and ‘advance civilisation by thousands of miles.’

An early beneficiary of Mahan’s ideas was President McKinley. Even more receptive to such notions was his Assistant Secretary of the Navy, one Theodore Roosevelt. In 1898, during McKinley’s presidency, the US waged war against Spain under the guise of liberating Cuba. Ultimately, however, it ended up annexing territories including the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii.

While ‘yellow journalism’ may have enhanced the war’s emotional appeal, such victories reinforced Mahan's earlier narrative. This consolidated the emotional foundations of America’s Self, and fed the country's appetite for sea power.

Throughout the twentieth century, the emotional symbolism of naval strength helped propel the US to becoming a superpower shaping the rules of the international system

When, in 1904, President Roosevelt oversaw the construction of the Panama Canal to unite the Atlantic and Pacific fleets, Mahan was an international figure, and sea power already inscribed in America’s Self. Throughout the twentieth century, this trend continued, and sea power became a core emotional element infusing America’s Self with a ‘controlled hallucination’ of stability, continuity, and determinism. It helped propel the US to become a superpower whose naval capabilities shaped the rules of the international system.

Whether deliberate or not, by carving out an unusual Gulf of Mexico-McKinley-Panama link, Trump touches a nerve which gives an important emotional tone to his geopolitical goals. His often-provocative speeches take place in communication channels ripe for stirring emotions — whether on X or, increasingly, in podcasts.

To use neuroscientist Andy Clark’s terminology, Trump 2.0 might be ‘hacking’ the ‘American Self’. He is evoking historical narratives and past experiences that create alternative mental images of the US, and pursuing a sense of ontological security that is emotionally nurtured by his own supporters. If his ideas take root more widely, they could pose a grave risk to global geopolitical stability.