Populist attitudes are responsive to perceived improvements in the democratic system. Marie-Isabel Theuwis and Rosa Kindt argue that this makes them a useful means to assess democratic quality

Populism has an ambivalent relationship with democracy. It affirms the core democratic principle of power to the people, but is rigorous to the point of zealousness in its pursuit of this principle. This leads, for instance, to the rejection of mediated representation. Such tendencies uphold the idea that populism is a threat to democracy or even – when referring to its radical-right manifestation – a ‘democratic pathology’.

To stay in medical terms, we could also take populism as a symptom: a sign of something going on deeper under the surface. Others have therefore posited that the populist fixation on popular sovereignty means populism emerges when the democratic practice falls short of the democratic ideal. That is, when political elites are revealed to be indeed corrupt. But that is also when the everyday realities of how representative democracy works in practice leave too little room for ‘the voice of the people’.

Populists strongly support democracy as an ideal, but are more likely to express dissatisfaction with a perceived lack of responsiveness to 'the will of the people'

Research shows that populist citizens are especially likely to pick up on the gap between democratic practice and democratic ideal. This is because they are democratic idealists: they strongly support democracy as an ideal and even support most liberal democratic values. The flipside of this is that populist citizens are more likely than other citizens to express dissatisfaction with a perceived lack of responsiveness to ‘the will of the people’.

The purpose of democratic innovations is to deepen or extend the role of citizens in democratic decision-making. Participatory budgeting (PB) does so by giving citizens authority to decide on the allocation of part of the local budget. Usually, citizens discuss in groups how to spend the budget, after which they make the final decision through a vote. Even though PB sometimes falls short of this ideal, its design enhances the level of popular sovereignty in a democracy.

Populist citizens perceive that popular sovereignty in our representative democracies is lacking. The question, therefore, is whether they would perceive a tool that seeks to address this shortcoming as a viable solution. Previous research has shown that populist citizens are highly supportive of decision-making processes that take power away from the elite and give it back to the people. This support extends to direct democratic decision-making (referendums) and, contrary to what one might expect, deliberative forms of democratic decision-making (citizens’ assemblies).

Research shows that populist citizens are highly supportive of decision-making processes that take power away from the elite and give it back to the people

Support in the abstract has no real connection with perceptions in practice. We thus still know very little about how populist citizens experience democratic innovations, such as participatory budgeting, when they take place. Do such citizens indeed perceive participatory budgeting as increasing the power of the people?

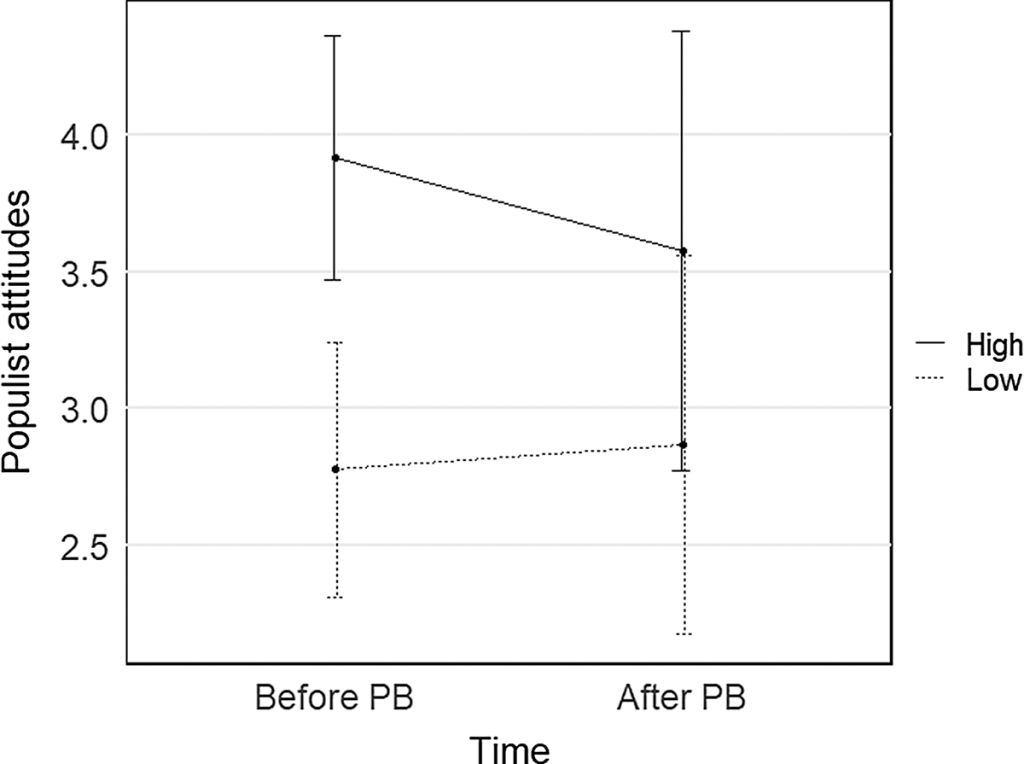

In a recent study, we went beyond populist citizens’ support in the abstract and studied whether there is a change in level of populist attitudes among participants to real-life participatory budgeting events. We attended four local PB meetings and measured populist attitudes among all participants before the PB and directly after it. This allowed us to create a dataset with which to study change in populist attitudes as a direct result of participation in a PB. We also conducted interviews with populist and non-populist participants to gain further insight into how they experienced such a decision-making process.

We found that among populist participants, participation in a PB led to a significant decrease in populist attitudes. Non-populist participants’ populist attitudes did not significantly change. This suggests that something happened during the PB that directly connected to populist attitudes, but the data could shed no further light on that.

However, from the interviews with populist participants whose populist attitudes dropped, we gained two key insights. Firstly, they perceived that the process engaged them in political decision-making. Second, they felt that the politicians and authorities present afforded them respect and recognition. Participants saw how the latter listened and appreciated citizen input. This suggests strongly that populist participants experienced the process as truly and respectfully giving some power back to the citizens. As one populist citizen noted afterwards:

...politicians go to the residents and listen to what they have to say, but also the other way around. Look, now residents have a little influence on politics, and vice versa. It should be a two-way street and not a one-way street

Taking these findings beyond our study, we think they suggest that populism in citizens is closely related to whether citizens feel they have influence and authority in democracy. Populist citizens are ‘dissatisfied democrats’ who feel there is not enough popular sovereignty in modern democracies. Democratic innovations such as PBs give authority and influence to citizens. Participation in a PB decreased the level of populism among these ‘dissatisfied democrats’. This indicates that in those citizens' eyes, participatory mechanisms did indeed diminish the gap between democratic ideal and democratic practice.

Is populism a pathology or a symptom of some underlying problem? Is populism a threat or a corrective to democracy? Our research shows that populist citizens respond to processes that bring actual democracy closer to their ideal democracy. This could indicate that, among citizens at least, populism functions as a symptom of a perceived concentration of power in the hands of the elites at the expense of popular sovereignty. Moreover, populist citizens do not necessarily prefer non-democratic forms of decision-making, but are rather opposed to mediated representation. Instead, when democratic practice approaches more participatory forms of democracy, populist citizens’ satisfaction increases.

This research was funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), NWO-VIDI 195.085

No.84 in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more