The Italian cabinet, led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, has approved a proposal to revise the Constitution, chiefly through introducing the direct election of the Prime Minister. However, writes Roberto Baccarini, the reform may in fact undermine Prime Ministerial authority, and would destabilise other existing institutional arrangements

In November 2023, the right-wing cabinet, comprising Fratelli d'Italia, Lega and Forza Italia, agreed on a proposal to revise Italy's Constitution. The cabinet proposed the direct election of the Prime Minister, effectively overturning Italy’s current institutional arrangements.

Italy has a parliamentary form of government based on the balance of power. The President of the Republic is elected every seven years by both houses and regional delegates. The President of the Republic appoints the Prime Minister, whose government is subject to a vote of confidence in both houses of the parliament (Article 92-96 of the Constitution). The proposed reform would overturn this balance, by introducing the direct election of the Prime Minister.

This, according to Meloni, would: ensure that the public choose who governs them; empower the Prime Minister by securing a stable majority and a full term of office; and safeguard the role played by the President of the Republic.

Meloni believes the reforms will empower the Prime Minister by securing a stable majority. On the contrary: the reform is likely to destabilise Italy's governmental system

Yet it is highly doubtful that the proposed reform would achieve these goals. On the contrary, the reform is likely to have destabilising consequences for the Italian governmental system.

The proposed constitutional reform states that if the directly elected Prime Minister resigns or loses the confidence of the chambers, the government can replace him/her. This may happen only once, and the substitute must belong to the coalition supporting the outgoing Prime Minister.

Under the proposed reform, the Prime Minister may be directly elected, but they would also be easily dismissible by a parliamentary majority

So, directly elected the Prime Minister may be, but they are also easily dismissible by a parliamentary majority. This new Prime Minister would be indirectly elected and could not be dismissed unless the parliament were dissolved. The directly elected Prime Minister could thus become a giant with feet of clay.

The proposed constitutional reform will also weaken the role of parliament.

First, it proposes assigning to the coalition supporting the candidate elected Prime Minister a ‘premium’ guaranteeing that coalition 55% of the seats in both houses. The reform therefore reverses the link between parliament and government. In the current system, the outcome of the parliamentary elections decides the composition of the government. With this reform, the outcome of the election of the Prime Minister would decide the composition of the parliament.

Second, the reform jeopardises the nature of the Italian upper house. In the Italian system, the Senate of the Republic is elected on a regional basis according to Article 57 of the Constitution. However, following this reform, the ‘premium’ would be assigned nationally. So this reform will undermine the connection between the Senate and the regions.

Third, this reform will effectively transform the election of the parliament into a second-order election. No matter how well a political party performs in the parliamentary elections, direct election of the Prime Minister will decide the award of the ‘premium’.

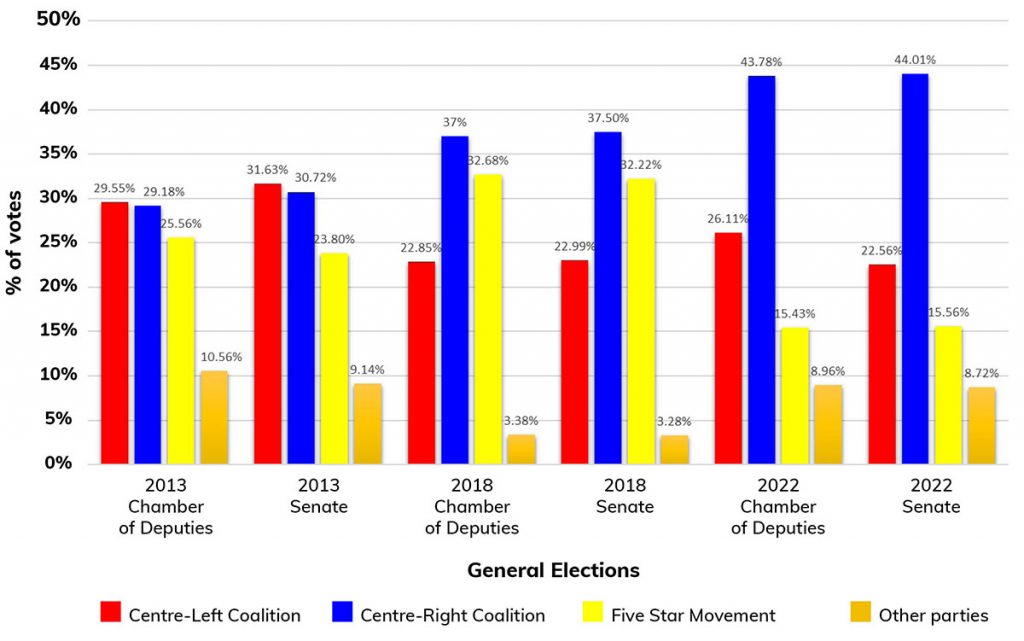

Finally, to be granted the ‘premium’, there is no minimum threshold a coalition has to reach. This graph plots the percentage of votes received by each coalition in the last three general elections. It shows clearly how these elections produced a genuine multi-party system. Italy’s is a ‘mixed’ system with proportional and majoritarian elements. For the 2018 and 2022 elections, the data thus refers to the proportional part of the electoral system.

These figures suggest that, if the proposed constitutional reform were approved, there is a tangible risk that a coalition representing less than 45% of the votes would end up controlling the government, and both houses, with a 55% majority.

The main loser from this reform would be the President of the Republic. The President formally retains the task of nominating the Prime Minister and the Ministers on the suggestion of the former. Remember, however, that the President is indirectly elected by the parliament. It seems unlikely, therefore, that an indirectly elected President would be in a position to contest the outcome of the direct election of the Prime Minister, or the ministers chosen by the winning candidate. If this were the case, the President’s role would be nothing more than rubber-stamping decisions made elsewhere. In this sense, the Presidency would lose its current crisis-management role in government – something that has been particularly important in Italian politics.

The main loser from this reform would be the President of the Republic

The ‘premium’ also jeopardises the independent election of the President. Currently, to elect the President, the Constitution (Article 83) prescribes a two-thirds majority for the first three ballots and an absolute majority thereafter. Thus, the winning coalition is likely to determine, by itself, who should be the next President of the Republic.

Prime Minister Meloni calls it the ‘mother of all reforms', but it is unlikely to meet her aims. The reform fails to strengthen the role of the Prime Minister through direct election. It also hollows out the role of the President of the Republic and the parliament. Its controversial nature means it is likely to be amended in the approval process, especially as, to become a reality, it will have to overcome several hurdles.

Moreover, even if the ruling coalition gets enough votes to pass and approve the reform in parliament, the bill’s approval would need two-thirds support of the members of each house to avoid a constitutional referendum, a majority Meloni’s coalition lacks.