China and Russia march in unison on the global stage. Behind the choreography, however, lies a partnership of limits and unequal leverage. United in criticising Washington and trading weapons, the two countries diverge sharply on nuclear doctrine. Mariam Mumladze shows how shared opposition to the West conceals deeper strategic differences, exposing the limits of their so-called 'no-limits' partnership

Following the elaborate parade on Tiananmen Square, China and Russia reaffirmed the strength of their no-limits strategic partnership. According to their Joint Statement from May, the two countries claim their relationship is built upon shared aspirations for 'equal and indivisible security' and parallel narratives condemning US-led alliances, missile defence initiatives, and the militarisation of space.

These positions reflect China and Russia's common opposition to what they view as Washington’s pursuit of unilateral strategic superiority. Yet beneath this rhetoric of unity, their cooperation is strongest in public shows of force — joint military drills and selective technology transfers — while clear boundaries remain in the nuclear domain. Scholars often describe this pattern as a limited alignment — strategic coordination that stops short of genuine alliance.

China and Russia's cooperation is strongest in public shows of force, while clear boundaries remain in the nuclear domain

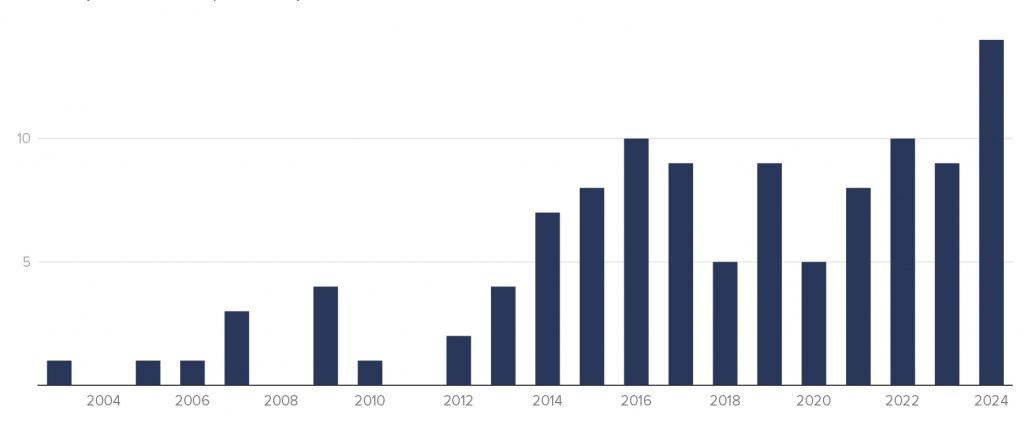

As the graph below shows, joint military exercises and arms sales suggest an increasingly coordinated front. Since 2014, Russia and China have deepened security cooperation, their joint exercises growing more frequent and complex. The 'Joint Sea' naval drills, held since 2012, now include submarine operations and anti-submarine warfare. Russian and Chinese bombers have conducted coordinated patrols over the Sea of Japan and East China Sea. In 2021, the two militaries carried out their first joint strategic bomber patrol with planes capable of carrying nuclear weapons. The patrol was designed to send clear signals to Washington and Tokyo.

Technology transfers also highlight the growing cooperation. Russia has sold China advanced systems such as the S-400 air and missile defence system and Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets. These deals were approved in 2014, as Moscow turned eastward following Western sanctions over Crimea. In 2019, Vladimir Putin disclosed that Russia was assisting China in building a missile attack early-warning system, a capability previously reserved only for Russia and the United States. Such cooperation goes beyond symbolic drills, extending to shared expertise in radar, sensors, and the integration of missile defence networks. These steps demonstrate what analysts call 'functional interdependence', where each partner exploits the other’s strengths without merging broader strategic goals.

Beneath this, the clearest boundary in Sino-Russian military relations lies in their nuclear doctrines. Putin’s 2020 decree allows the use of tactical nuclear weapons in two cases. One of these is in the event of conventional aggression that 'threatens the state’s existence'. This expands Russia’s options and creates a legal basis for its escalate to de-escalate approach, meaning Moscow might use a small nuclear strike to force an enemy to back down. This strategy helps compensate for conventional weakness and aims to deter NATO from giving further support to Kyiv.

Meanwhile, China recently showcased new versions of its Dongfeng intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of carrying multiple warheads. Yet Defence Ministry spokesman Zhang Xiaogang reaffirmed Beijing’s longstanding no-first-use policy:

We always maintain our nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required for national security, and do not engage in any arms race

Chinese leaders have also signalled unease with Russia’s nuclear posture. During Xi Jinping’s 2023 visit to Moscow, he reportedly warned Putin against using nuclear weapons in Ukraine, and explicitly condemned nuclear threats. This marked a subtle but important boundary — Beijing values the partnership but does not endorse nuclear intimidation. The contrast illustrates what international relations theorists describe as strategic restraint: using cooperation to manage — but not mirror — another power’s risk-taking.

China appears interested in selectively acquiring Russian know-how and pursuing a more cautious nuclear doctrine. Its nuclear arsenal, estimated at around 600 warheads in 2025 and growing by roughly 100 warheads annually since 2023, is seen primarily as a defensive response to US military modernisation.

| Deployed warheads | Stored warheads | Military stockpile | Retired warheads | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 2025 | 2024 | 2025 | 2024 | 2025 | 2024 | |

| United States | 1,770 | 1,930 | 3,708 | 3,700 | 1,620 | 1,477 | 5,328 |

| Russia | 1,718 | 2,591 | 4,380 | 4,309 | 1,200 | 1,150 | 5,580 |

| United Kingdom | 120 | 105 | 225 | 225 | - | - | 225 |

| France | 280 | 10 | 290 | 290 | - | - | 290 |

| China | 24 | 576 | 500 | 600 | - | - | 500 |

| India | - | 180 | 172 | 180 | - | - | 172 |

| Pakistan | - | 170 | 170 | 170 | - | - | 170 |

| North Korea | - | 50 | 50 | 50 | - | - | 90 |

| Israel | - | 90 | 90 | 90 | - | - | 90 |

| Total | 3,912 | 5,702 | 9,585 | 9,614 | 2,820 | 2,627 | 12,405 |

The Joint Statement reflects concern that Washington’s pursuit of a layered missile defence system, alongside developments in long-range conventional strike and hypersonic weapons, could undermine China’s ability to retaliate in case of attack. This is what strategists call China's 'second-strike capability'. If the US could reliably intercept or neutralise Chinese missiles, Beijing’s nuclear deterrent would be at risk. This explains China’s focus on diversifying its nuclear delivery systems across land, sea, and air, including road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles, ballistic missile submarines, and nuclear-capable bombers.

Still, China’s nuclear policy remains cautious, and its strategic independence intact. This mix of modernisation and restraint shows Beijing’s attempt to maintain credible deterrence without mirroring Moscow’s risk-prone behaviour — a balance that underlines its preference for stability over brinkmanship.

For policymakers, the implication is clear — the Sino-Russian partnership should be recognised but not overstated. Cooperation is strongest in shared criticism of the West and selective military exchanges, yet nuclear strategy remains a dividing line. One country wields nuclear weapons as tools of blackmail; the other remains reluctant to cross that threshold. The pattern fits a broader trend: asymmetric partnerships in which weaker states rely on symbols of unity while stronger ones hedge to preserve autonomy.

Sino-Russian cooperation is strongest in shared criticism of the West, yet nuclear strategy remains a dividing line

Beyond this cooperation, Russia appears far less formidable than the USSR of the past. Signs of vulnerability are evident — from China’s quiet push to build a modern container port in Slavyansk Bay, in Russia’s Far East, to the linguistic shift of referring to Vladivostok by its pre-Russian name, Haishenwai. These developments highlight Moscow’s growing dependency on Beijing and its shrinking room for manoeuvre.

In the near future, Russia’s weakness may create a moment of adjustment in the global order. Whether other powers can adapt to this shifting balance remains to be seen. What is certain is that China and Russia’s no-limits partnership has limits after all — limits that expose both the hierarchy and fragility of their strategic alignment.