The role of the private sector is often overlooked in evaluating a country’s performance on human rights. Eduardo Burkle and Ella Fraser explore new data showing how private sector actions can be damaging to human rights. The potential for the private sector to improve human rights exists, but is currently untapped

We all know money talks. The private sector can exercise enormous influence over governments, for good and for ill. But in how many ways can this happen? During 2022, we at the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) studied the impact of private sector influence on human rights, in a selection of countries.

HRMI uses a multilingual expert survey method to create metrics on human rights performance for eight civil and political rights. The survey also allows us to gather data on which groups of people the respondents identify as at greater risk of suffering human rights violations for 13 human rights, including five economic and social rights. Additionally, the survey gathers qualitative responses presented as 'people at risk' data on HRMI's Rights Tracker. This allows respondents to provide deeper insight into human rights violations in their countries.

Included in this year's survey were three pilot questions on the influence of private sector actors on physical integrity rights, empowerment rights, and economic and social rights. Respondents in Angola, Australia, Brazil, India, South Korea, and the United States were given the opportunity to answer them. We collected responses using the following question template:

'In [your country], have domestic or foreign investors, banks, economic advisors, or corporations recently encouraged or discouraged policies or practices that affect government respect for (physical integrity / empowerment / economic and social rights)? If so, how?'

Across all the countries, respondents told us the private sector had an overall negative impact on human rights. This was often attributed to prominent lobbying and/or political power, particularly opposition to labour rights. But there were other examples, too. These included attempts to suppress or punish protestors; the spreading of misinformation; the degradation of environmental rights; and abuses in private detention facilities. However, respondents in a few countries also described some positive impacts of the private sector.

According to survey respondents, private sector actors had two different kinds of negative impacts on human rights. The first is their own behaviour. For example, in Brazil, mining and agri-business companies have reportedly evicted communities and hired paramilitaries to intimidate Indigenous people, environmental activists, and journalists.

Second, the private sector has lobbied for direct benefits for corporations or individuals. It has also exerted political pressure to approve policies and legislation favourable to investors and corporations.

private sector actors can influence human rights directly, through their actions, and indirectly, by lobbying on behalf of corporations or individuals

Taken together, we see an overarching trend. Respondents reported the private sector as being opposed to many government interventions, including public funding, higher taxes, and environmental and labour protections. Perhaps ironically, data from Australia highlighted how companies welcomed government action in support of business during the Covid-19 pandemic.

On a positive note, private media companies have provided checks on the government, supporting empowerment rights. Also, in Angola, private sector banks, investors and the media supported the inclusion of lower socio-economic groups in the country's economy.

Elsewhere, Indian legislation obliged large companies to allocate a percentage of their profit towards charities. Some American companies and institutions, meanwhile, have encouraged environmentalism and provided workers with healthcare or educational support.

The negative impacts of private sector actions were clearly worse for Indigenous people, minorities, and lower socio-economic groups. Respondents in South Korea reported discrimination against women in the hiring processes of large companies. In Australia and the United States, detainees at private prisons and migration detention centres experienced ill-treatment and violations of physical integrity rights.

negative impacts of private sector actions were clearly worse for Indigenous people, minorities, and lower socio-economic groups

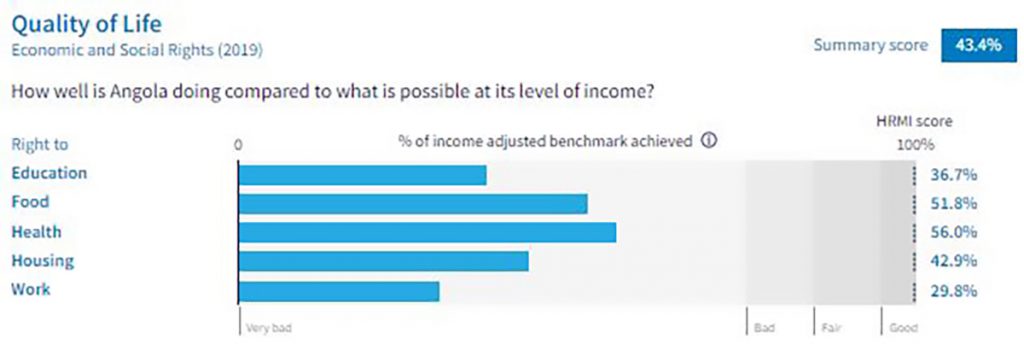

A closer look at HRMI's Rights Tracker provides quantitative context for respondents' answers. Take, for example, Angola’s quality of life scores:

Angola is performing worse than average compared with other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. It falls well short of its human rights obligations across all five scores. The lowest score is for the right to work, where Angola is achieving only 29.8% of what ought to be possible at its current level of income. This falls in the ‘very bad’ range. Tellingly, respondents reported the undermining of labour rights in the private sector. This also provides an example of where the private sector could influence governments for good: as investors and companies join the Angolan economy, they have the potential both to directly contribute to better outcomes and to lobby the government for policies that put people first.

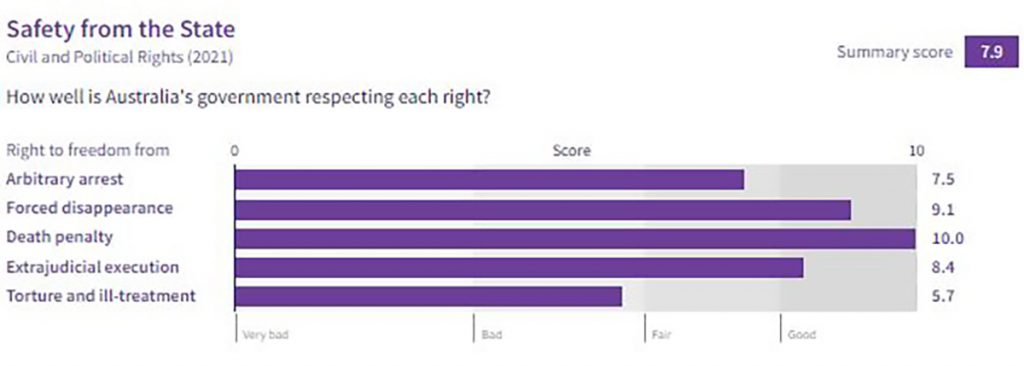

HRMI scores on the right to freedom from torture and ill-treatment in Australia and the United States also reflect respondents’ concerns. This right has the lowest score in the safety from the state category for each (5.7 and 3.8 out of 10, respectively). Responses in both countries mentioned abuses in the treatment of detainees in private prisons and migration detention centres.

Human rights measurement projects often focus on detecting human rights violations per se without taking a step further in naming specific groups as victims or perpetrators. Gathering qualitative and quantitative data directly from human rights experts provides more nuanced information on violations.

States are often at the centre of analysis of human rights violations, either through direct action or omission. However, it is undeniable that private sector actors can influence the enjoyment of rights in a country. We see this in the recent withdrawal of foreign companies from Russia, and South Africa before that. Respondents reported in 2022 that the private sector's impact on human rights is largely negative. But it doesn’t have to stay like this. HRMI calls on private sector actors to use their influence to improve human rights worldwide, and to build a world where everyone can flourish.

Final note: the inclusion of these new questions in our 2022 survey was a pilot. We are keen to learn more about the usefulness of the responses and explore how we might better collect information on the many ways money talks. If you have got thoughts or ideas, we’d love to hear them!