Accepting electoral defeat is essential for democratic stability. Yet, recent tumultuous events in the US and Brazil suggest that losers’ consent becomes harder to obtain in polarised times. Using case studies from UK elections, Lisa Janssen explains how polarisation influences citizens’ responses to election results

The storming of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 marked a low point in the history of American democracy. A crowd of Trump supporters attacked and invaded the Capitol building in an attempt to prevent the certification of Joe Biden’s electoral victory.

Two years later, history seemed to repeat itself. This time, however, Brazil was the victim. Shortly after President Lula’s inauguration, violent Bolsonaro supporters marched to the Three Powers Plaza in the capital, Brasília. The mob attacked and invaded key federal government buildings, seeking to disrupt the peaceful transitioning of power.

These events hold crucial insights. They lay bare the deep polarisation gripping both nations. But they also illustrate the importance of losers’ consent; that is, electoral losers’ willingness to voluntarily accept the election result, even though it might not have been the outcome for which they had hoped. It is these two phenomena – polarisation and losers’ consent – that might prove incompatible.

Some polarisation is healthy – possibly even essential – for democracies. But extreme polarisation can pose serious risks. When political polarisation becomes extreme, citizens divide into camps with profoundly different, perhaps irreconcilable, worldviews. As a result, political opponents can come to treat each other with contempt and hostility. Indeed, research shows that partisans tend to perceive political opponents as immoral, evil – and even as a threat to the nation.

In deeply polarised societies, the political opponent is no longer a legitimate adversary but an enemy that must be vanquished

Amid this deep polarisation, the stakes of elections rise dramatically. The political opponent is no longer a legitimate adversary but an enemy that must be vanquished. Voters thus experience electoral defeat as a catastrophe they find painful to accept.

My recent European Journal of Political Research article explores how polarisation influences citizens’ response to electoral victory and defeat. Specifically, I use panel data from the 2015 and 2019 UK general elections to analyse the impact of elections on citizens’ satisfaction with democracy.

In both elections, the Conservative Party gained a majority of seats in the House of Commons, allowing them to govern without the need for a coalition partner. As such, those who voted for the Conservative Party are considered the electoral winners.

Ideologically polarised citizens view the policy stances of competing political parties as diametrically opposed

My study looks into two specific sub-types of political polarisation: affective polarisation and perceived ideological polarisation. Affective polarisation is citizens’ tendency to dislike and feel hostile towards the political opponent, while holding favourable attitudes towards their own political camp. Perceived ideological polarisation, by contrast, evolves around ideological rather than identity divides. It concerns citizens’ idea of how different the ideological positions of parties are. High levels of perceived ideological polarisation indicate that citizens view the policy stances of competing political parties as being diametrically opposed.

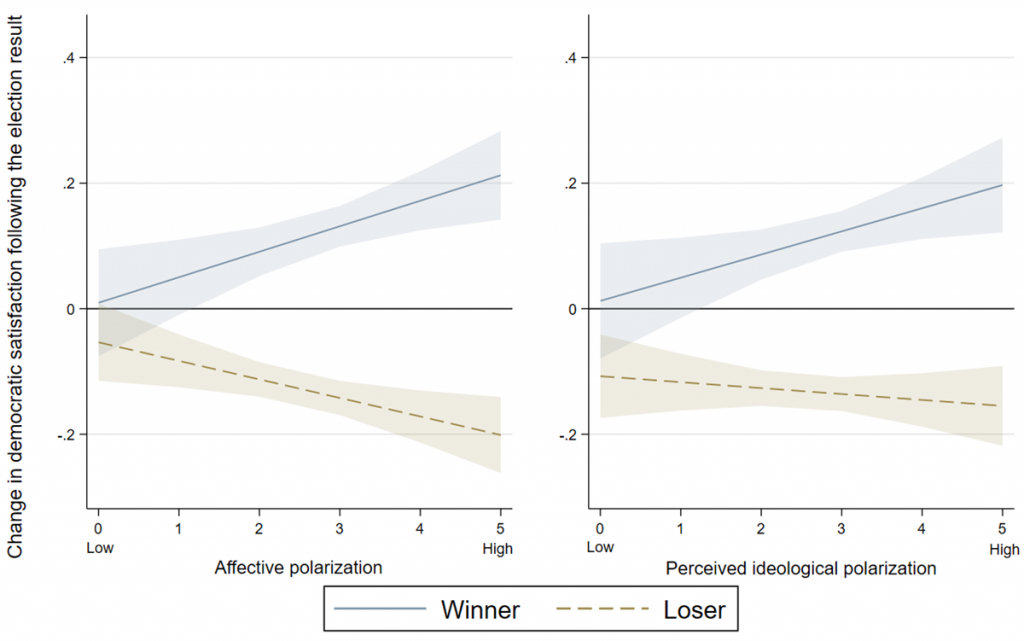

The figure below visualises the findings for the 2015 general election. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it shows that electoral winners become more satisfied with the way democracy works following the election. The opposite is true for electoral losers, who, on average, become less satisfied.

More importantly, however, the results reveal that polarisation exerts a strong influence on citizens’ response to the election result. Polarised losers experience a significant drop in democratic satisfaction following their electoral loss. This is true for both affective and perceived ideological polarisation. But it's not only the losers who are affected. Polarisation also seems to amplify the honeymoon of an electoral win. This is indicated by the stark increase in the democratic satisfaction of polarised electoral winners after the election.

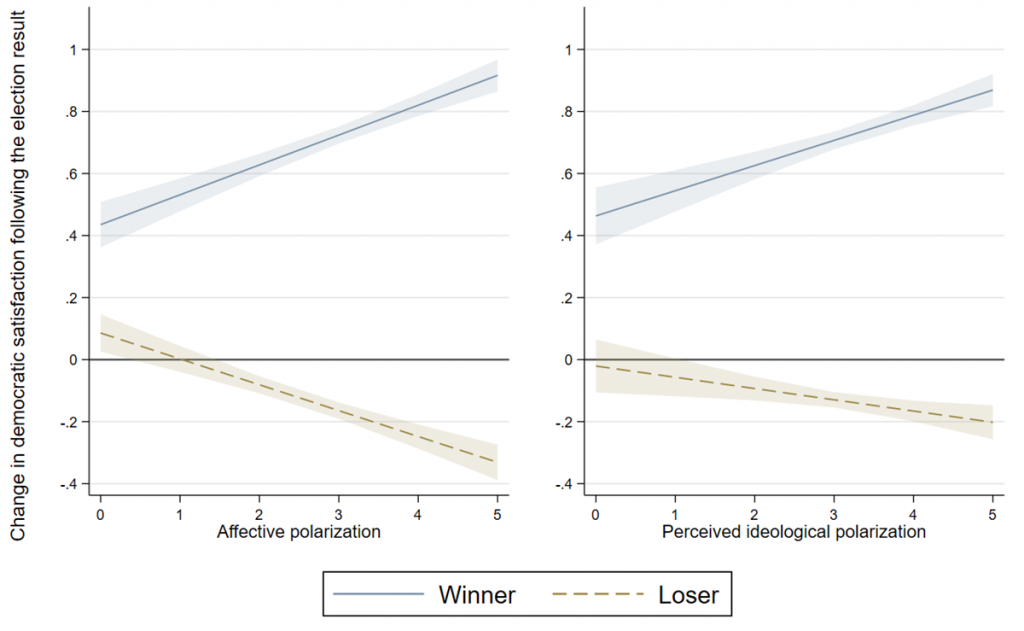

I repeated the same analysis for the 2019 UK general election. Overall, the results closely resemble those from 2015. Again, I find that polarised losers become substantially less satisfied with democracy following their loss. Notably, however, the effects have become much stronger in 2019. This suggests that polarisation is playing an increasingly important role in citizens’ response to election results.

What do these findings mean for the stability of democracies in election times? Democracies are dependent for consolidation on the consent of electoral losers. As such, few would dispute that retaining the political support of electoral losers in the aftermath of elections is vital.

My study shows that polarised winners and losers react to election outcomes in completely opposite ways. More importantly, I reveal how polarised voters' satisfaction with democracy plummets following electoral loss. Corroborating recent attacks on democratic institutions in the USA and Brazil, the findings do indeed suggest that polarised voters are less likely to comply voluntarily with unfavourable election outcomes.

Polarised citizens' support could thrive or crumble depending on the election outcome

Ultimately, the study raises serious concerns for losers’ consent and the stability of democracies during elections. It shows not only that losers’ consent might be more difficult to obtain in times of deep polarisation, but also that polarised citizens' levels of political support are unstable – they could thrive or crumble, depending on the election outcome.

Given the high levels of polarisation in many countries across the globe, my research suggests that the political support levels of substantial proportions of the population may become more fragile and volatile, especially at election times. Worryingly, uprisings such as those in the USA and Brazil may not be confined to the past.