Disabled people are underrepresented in elected office. It's unlikely, therefore, that public policy will reflect the interests of the 15% of the population living with disability. Stefanie Reher argues that we need to better understand the causes and consequences of such low representation

The World Health Organisation estimates that around 15% of the world’s population – over one billion people – live with a disability. At the same time, disabled politicians are a rarity.

Official statistics are lacking, but in many democracies only around 1% of legislators live with a disability. A few countries, including Uganda, have adopted parliamentary quotas for disabled people. But even these tend to be very low.

This underrepresentation is problematic for several reasons. For one, it signals that equal access to elected office – an important principle of democracy – is not a given. It also means that disabled people might not have a strong voice in the policies that shape their lives.

Political scientists have studied extensively how the presence of members of a group in positions of power affects the representation of that group’s interests in policy. Literature studying representation of women and ethnic minorities abounds. So far, however, research has largely overlooked disabled people.

For a new study in the British Journal of Political Science, I analyse survey data from citizens and election candidates in the UK. My aim was to establish whether disabled politicians better represent the policy preferences of disabled citizens.

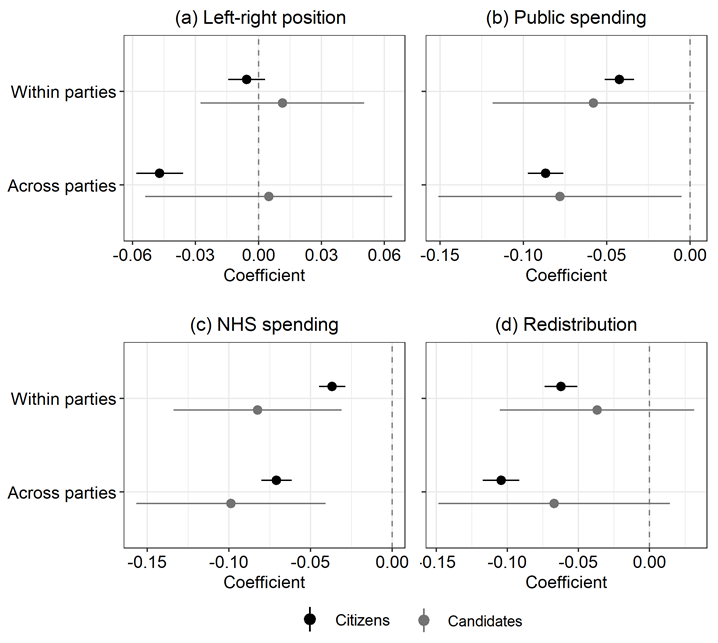

Some key distinctions in the opinions of disabled and non-disabled citizens are also present among candidates. Notably, disabled citizens and candidates are more supportive of healthcare spending, as well as general public spending, than their non-disabled peers – see Figure 1, below.

This suggests that increasing the number of disabled people in positions of political power might lead to improvements in the lives of those living with disability. Many disabled people continue to experience exclusion and discrimination in areas including education, employment, healthcare, and family life.

So why are there so few disabled people in politics, and how can their participation be improved? In a piece for International Political Science Review, Elizabeth Evans and I explore this question. Our interviewees included over 50 current and former British MPs and local councillors, and former election candidates. We also talked to people who had stood for selection, or considered doing so.

We revealed an ableist culture in which the needs and the potential of disabled people are often ignored

Our diverse sample of interviewees included, among others, D/deaf people, wheelchair users, neurodivergent individuals, and those with long-term mental health conditions. All reported encountering hurdles at each stage of the political recruitment process. These included standing for selection as a party candidate, and running an election campaign.

The nature of the barriers differed depending on the person's particular impairment. But the resulting experiences of being excluded or disadvantaged were often similar.

Travelling long distances to attend party meetings or conduct door-to-door canvassing can be equally challenging for individuals with mobility impairments and autistic people. The fast and sometimes aggressive culture of debating can disadvantage British Sign Language users as much as people with anxiety.

Many barriers could be eliminated simply through greater awareness and effort

Lack of accessibility, along with money for reasonable adjustments, are the main barriers to participation. Our research also revealed an ableist culture in which the needs and the potential of disabled people are often ignored.

Many barriers could be eliminated simply through greater awareness and effort. Political parties, for example, could choose accessible venues and think creatively about adjustments to existing processes. Yet, sometimes, levelling the playing field requires money – and this introduces another dimension of unequal access. To remedy this, the UK government has piloted funds to support disabled candidates’ election campaigns. The Scottish government provides an Access to Elected Office Fund.

Most interviewees reported feeling supported. Some, however, experienced outright hostility from within their party or from political opponents who claimed that their disability rendered them incapable of fulfilling the task of an elected representative.

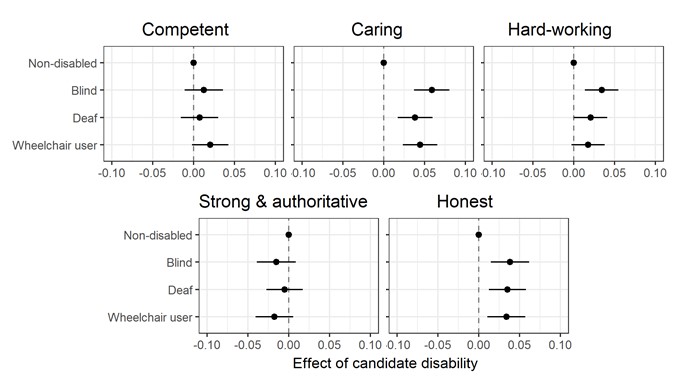

Do voters share such negative views? Dependent, weak, and vulnerable are the stereotypical perceptions of disabled people. This is at odds with the qualities we desire in political leaders. At the same time, we often encounter portrayals of disabled people as inspirational against-the-odds heroes.

some interviewees experienced outright hostility from those who claimed that their disability rendered them incapable of fulfilling the task of an elected representative

To study how voters perceive disabled election candidates, I conducted a survey experiment. My questionnaire asked respondents to evaluate fictional candidates based on a range of personal characteristics and markers of political experience. Random assignment of different characteristics allowed me to identify how each characteristic influenced respondents’ perception.

The resulting article appears in Frontiers in Political Science. In it, I show that candidates who are D/deaf, blind, or who use a wheelchair, are not seen as less competent or weaker than non-disabled candidates. On the contrary, voters perceive them as more compassionate, honest, and hard-working – see Figure 2, below. Respondents also viewed them as being more competent to handle policy on healthcare, social security, and minority rights.

Disability, it seems, does not render candidates less suitable for political office in voters’ eyes.

Where else, then, should we look to explain the low numbers of disabled people in politics? In addition to the lack of accessibility, financial barriers, and ableism within parties, the rarity of role models in politics might discourage many disabled people from getting involved.

Disabled people tend to have lower levels of trust in the political system and its responsiveness. This might be remedied by seeing that people who are ‘like them’ can indeed reach positions of influence in the system.