As climate policy costs rise, right-leaning voters experience cognitive dissonance. As a result, Sofia Henriks writes, they lower their worries about climate impact when there is an increase in private costs. But what about the left-leaning voters?

In recent years, few issues have attracted as much attention as the need to reduce carbon emissions on our planet. Despite a promising development in public opinion on support for climate mitigation policies, there is a strong divide between left and right in preferences terms, which presents a challenge for the green transition. To promote effective and sustainable environmental governance, it is therefore crucial to understand the root of this division.

There is a strong divide between left and right preferences on climate policies, which presents a challenge for the green transition

In a recently published Ecological Economics article, I and my co-authors Gustav Agneman, Hanna Bäck and Emma Renström found that right-leaning participants reacted to increases in the private costs of climate policies by reducing their support and lowering their worries. Left-leaning participants, however, did not.

Earlier research found that a range of factors, including income, education, and gender, as well as policy design and implementation, influences policy preferences. Those on the left of the political spectrum are typically more in favour of costly climate policies than those on the right. There is considerable evidence of an ideological divide. But we also find that political ideology conditions the way people react to rising policy costs:

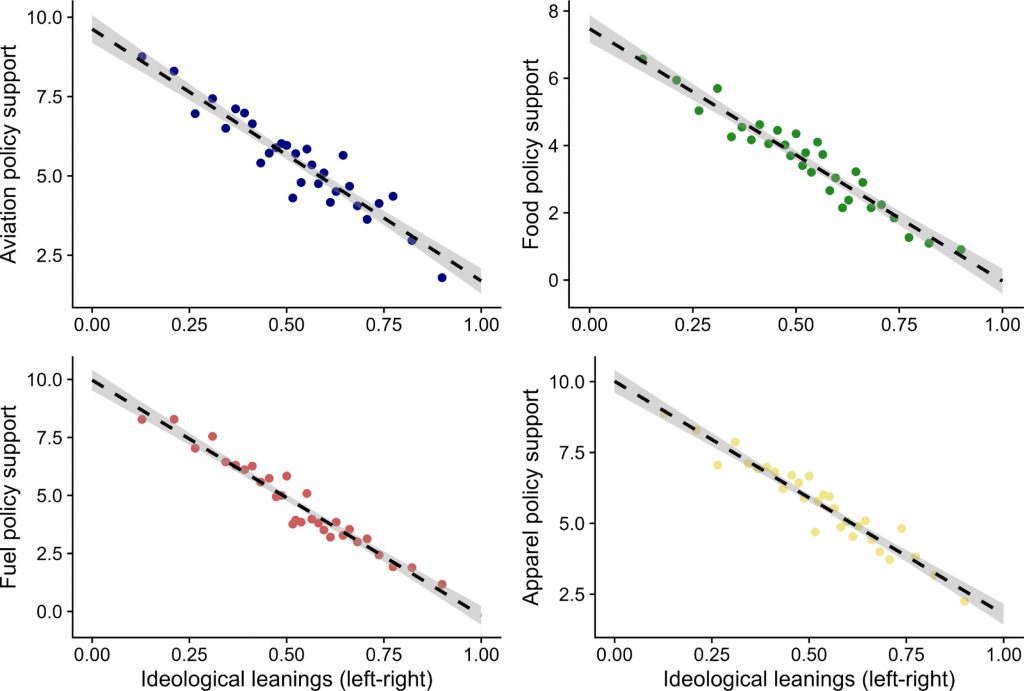

These graphs demonstrate strong relationships between political ideology and support for the four climate policies. Policy support declines monotonically as political ideology becomes more right-wing.

But why is the right more sensitive to private costs? There are numerous potential explanations, one of which is social norms. Research by Mathias Zannakis suggests that left-leaning individuals tend to follow stronger social norms related to climate behaviour than those on the right. Zannakis argues that while those on the right are open to weighing climatic benefits against economic cost, this trade-off thinking is more stigmatised among those on the left. This implies that if someone identifying with the ideological left would allow her own private material interest to dictate her disagreement with a climate mitigation policy, she would be prepared to pay a higher social cost than someone identifying with the ideological right, because of the norm violation.

That right-leaning voters are less likely to support climate mitigation policies at baseline, and more sensitive to cost increases, may come as no surprise. Yet, understanding why this divide exists, and why it may grow if the green transition becomes more costly, is crucial for policy makers interested in bridging the climate policy gap.

In an exploratory analysis, we find that right-leaning voters not only react to increased costs by reducing their support, but also that they worry less about climate impact when facing rising policy costs. Why is this?

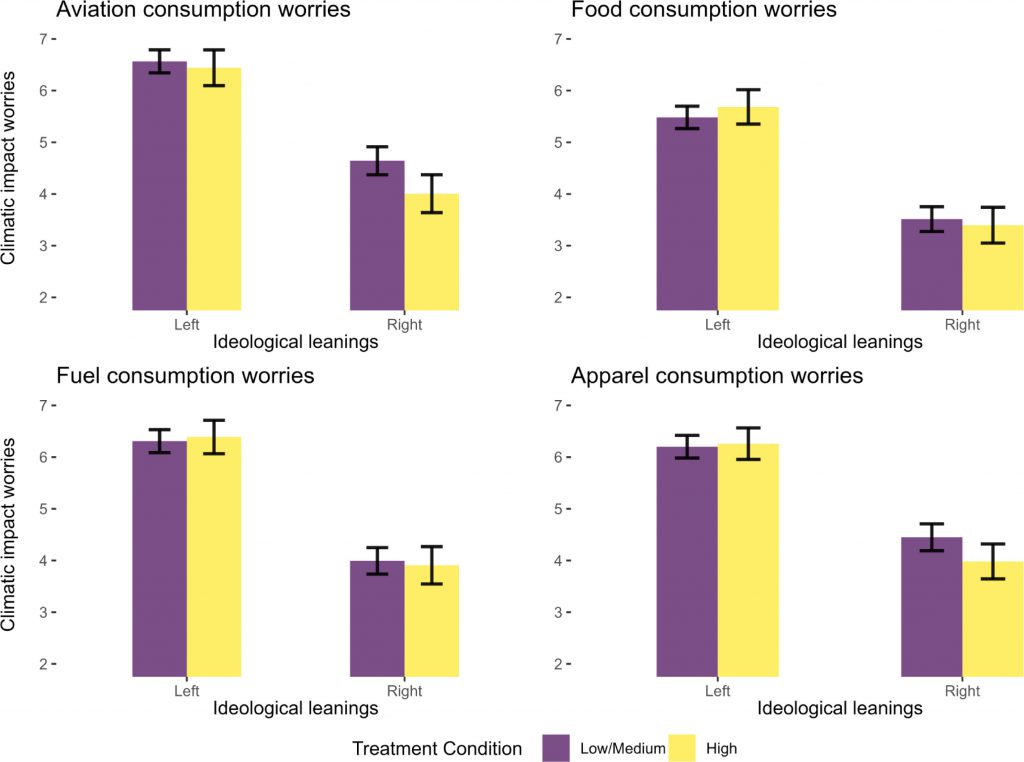

These graphs display reported worries about the climatic consequences of aviation, food, fuel, and apparel consumption, respectively, for left- and right-leaning participants and separately in low/medium-cost and high-cost conditions.

One reason why right-leaning voters might report lower levels of worries for climate change when presented with higher personal costs could be cognitive dissonance: the mental discomfort created by holding more than one conflicting belief at once.

In our daily lives, cognitive dissonance can occur in all sorts of situations. For example, we might decide we want to eat more greens, because we read that it's good for our health. But we fail to change our eating habits because we don't really like eating greens. We experience such cognitive dissonance whenever we are faced with contradicting thoughts and actions. To block the mental discomfort cognitive dissonance produces, we either have to start eating greens, or persuade ourselves that food science is pseudoscience, and that eating greens will not improve our health.

You might not be ready to reduce cognitive dissonance by changing your behaviour. You may instead change your mind about the issue, and worry less about the action

We want to reduce this mental discomfort as much as possible. That is, in part, why it is hard to accept that many daily activities – driving a gasoline car, buying (fast) fashion trends, flying on our vacation, eating meat – all contribute to global warming.

You might not be ready to reduce the cognitive dissonance by changing your behaviour – to replace meat with alternatives, stop buying new clothes, and change your travel habits. You may instead change your mind about the issue, and worry less about the action. This, of course, is an easier way to cope.

But why do right-leaning people experience this and not those on the left? There are multiple potential explanations. Our study does not address the 'why the right?' question. Even so, we found that left-leaning participants do not lower their support for climate policy even when there is an increase in the personal cost. Right-leaning participants, however, do. Thus, when right-leaning participants face a higher cost and lower their support accordingly, to lighten their mental discomfort, they must also lower their worries.

Left-leaning people do not lower their support for climate policy even when there is an increase in the personal cost. Those on the right, however, do

This sheds light on a significant divide between left- and right-leaning voters’ support for climate policies. While this ideological polarisation is not new, our findings highlight a striking difference in how these groups respond to policy costs.

As we move forward in addressing climate change, understanding these mechanisms and ideological divides will be crucial for developing effective and long-term climate mitigation policies.