The refugee crisis has led to changes in EU migration policy management. But effective reform of the so-called Dublin System that could resolve the crisis has so far eluded the EU. To understand the prospects for change, Danilo di Mauro and Vincenzo Memoli argue that we should examine how public opinion influences political parties, and elites

The public’s role in European integration of immigration policy has become central in recent electoral contests around the EU. But can public opinion really make a difference? Can it influence political elites' decision-making on such a highly politicised issue?

We can test this by examining the refugee reception crisis that began in the mid-2010s. The crisis was described in 2015 by EU Migration Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos as the world’s ‘worst refugee crisis since the Second World War.’

In 2015 and 2016, the EU received more than 1.2 million asylum applications, mainly on its eastern and southern borders. Most were made to Germany, Hungary and Sweden (Eurostat). This precipitated a a humanitarian crisis. Thousands of people spent prolonged periods in refugee camps, or even prison, enduring terrible living conditions. Between 2015 and 2016, a treacherous route through the Mediterranean Sea claimed the lives of around ten thousand people who braved its waters (UNHCR).

Since then, the EU has made progress in integrating refugee and immigration policies. It has become well versed in a core policy area usually reserved for modern nation-states.

The Euro crisis revealed the problems with common currency policies. The refugee crisis that followed exposed the structural deficiencies of common immigration policies. It also revealed flaws in the process of entry and border checks, known as the Dublin System.

the EU has pooled unprecedented financial resources, established missions, given new powers to the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, signed bilateral agreements with the countries of departure, and pushed for greater cooperation among member states

The EU’s response to the crisis has been impressive. Among other things, it has pooled unprecedented financial resources, established missions, given new powers to the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), signed bilateral agreements with the countries of departure, and pushed for greater cooperation among member states.

Yet despite these achievements, the refugee crisis has failed to reform the Dublin System and relocate asylum seekers. Indeed, EU institutions and member countries reached deadlock. But has public opinion helped block further integration of immigration policy?

Our recent article in the Journal of Common Market Studies investigates the relationship between public opinion and the opinions of the political elite regarding acceptance or rejection of immigrants. It also explores what level of government should decide immigration quotas.

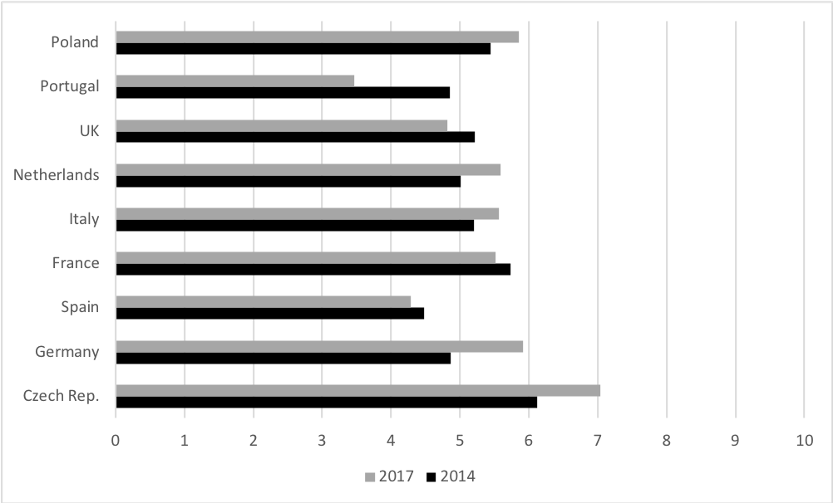

We observed a mutual convergence of positions of the general public, and of parties, toward restrictive migration policies. Our article samples data from nine countries: the Czech Republic, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom. Together, these represent more than 70% of the EU population. As the refugee crisis developed, political parties aligned with public opinion, becoming more restrictive towards immigration and generally shifting towards rejection.

According to statistical models developed from data gathered by the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, ‘in 2014, the Christian Democratic parties, the Regionalists and the Confessional parties stand out for their clear opposition to a restrictive policy on immigration (i.e. holding positive attitudes towards acceptance)’.

Under pressure from the concerned public, many parties co-opted stances on immigration from TAN (Traditionalist, Authoritarian and Nationalist) and anti-immigrant parties

These positions, however, changed dramatically during the refugee crisis. In 2017, most party families under analysis – including Socialists, Radical Left parties, the Liberals and the Greens – transitioned towards non-acceptance. Only the Confessional parties continued to strongly oppose restrictive immigration policies.

Under pressure from the concerned public, many parties co-opted stances on immigration from TAN (Traditionalist, Authoritarian and Nationalist) and anti-immigrant parties. The last of these are mainly Eurosceptic. We expected, therefore, that public rejection of immigrants would be related to conserving national prerogatives over immigration quotas and, consequently, to the opposition of further EU integration under the Dublin System.

To test this hypothesis, we used an Elite Survey conducted in 2016 as part of the Horizon 2020 project EUENGAGE. We pooled these findings with ESS data on public rejection. Analyses show that ‘the higher the percentage of the public rejecting extra-EU immigrants, the more political elites tend to prefer a national rather than an EU quota system. Moreover, political representatives tend to prefer national decision-making on quotas when they perceive that a majority of people supports this position.’

From a theoretical perspective, this study supports what is known as the ‘post-functionalist’ view of a ‘constraining’ public influence on EU integration. The study observes a public-elite relationship toward policy orientations, even in the absence of an electoral contest such as a referendum. From a policy-making perspective, it implies that the deadlock on reforming the Dublin System will persist if the issue is highly politicised.

The pandemic has dramatically reduced public concern about immigration. Look at most national media, and you might think the refugee crisis was over. This may also be attributable to the sharp drop in arrivals, which eased the pressure on national and EU institutions. Regardless, the problem of immigration quotas is still on the table, as are the inhumane conditions in EU border refugee camps.

The question remains: post-pandemic, will EU states and institutions be able to fill this humanitarian gap and reassure the public about their capacity to manage massive flows of people escaping war and poverty?

The handling of the refugee crisis since 2015 suggests they still have some way to go.