On 1 January, Hungary's six-month presidency of the EU Council ended, and the EU made the unprecedented decision to withhold aid to Hungary over rule-of-law violations. John Chin and Mirren Hibbert put these developments in the context of continuing democratic backsliding in Hungary – and divisions over the future of Europe

On New Year's day 2025, Hungary’s status was downgraded overnight from rotating EU president to EU pariah. The European Commission announced its decision to withhold $1 billion in aid from Hungary over rule-of-law violations. The EU has investigated Hungary’s potential breach of European values since 2018 under Article 7 of the Lisbon Treaty. It has taken until now, however, for it to impose any costs. On 7 January, the outgoing Biden administration accused a top aide of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán of corruption, and imposed sanctions.

As new EU Council president, Poland under Prime Minister Donald Tusk is trying to steer the EU agenda towards liberal internationalism and defence of Ukraine. Tusk wants to move away from Hungary’s conservative populist nationalism and opposition to support for Ukraine. Yet Orbán is working to position himself into becoming Donald Trump’s man in Europe. He recently visited Mar-a-Lago, and predicts that Trump’s second term presages a right-wing surge in Europe, in Hungary’s image.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is working to position himself as Donald Trump's man in Europe

Since 2010, Hungary under Orbán has been a poster child for democratic backsliding in central Europe. Whether Orbán succeeds in 'occupying Brussels' before the EU brings Hungary to heel has major implications for democracy’s future in Europe.

After the collapse of communism in 1989, Hungary enjoyed two decades as a liberal democracy. It joined NATO in 1999, the EU in 2004, and the Schengen zone in 2007. Incumbents regularly lost power, including Orbán, who first served as prime minister from 1998 to 2002. As late as 2009, Orbán’s Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Alliance was, Larry Bartels notes, a 'thoroughly conventional conservative opposition party' whose supporters were far from aggrieved populists. Democracy appeared consolidated.

But Hungary’s democracy deconsolidated quickly after the 2008 global financial crisis and the Gyurcsány scandal swept Fidesz to power in 2010. Winning 53% of the vote but 68% of national assembly seats, Fidesz wasted no time in turning Hungary in an illiberal direction. Orbán, a liberal-turned-Christian-nationalist, used Fidesz’ super-majority to launch a 'constitutional coup' and reduce legislative and judicial constraints on the executive. He then undermined academic freedom, media freedom, and civil society. He peddled conspiracy theories about a George Soros-led pro-immigration cabal.

In 2019, Hungary became the first EU member to be downgraded to 'electoral autocracy' by the V-Dem institute

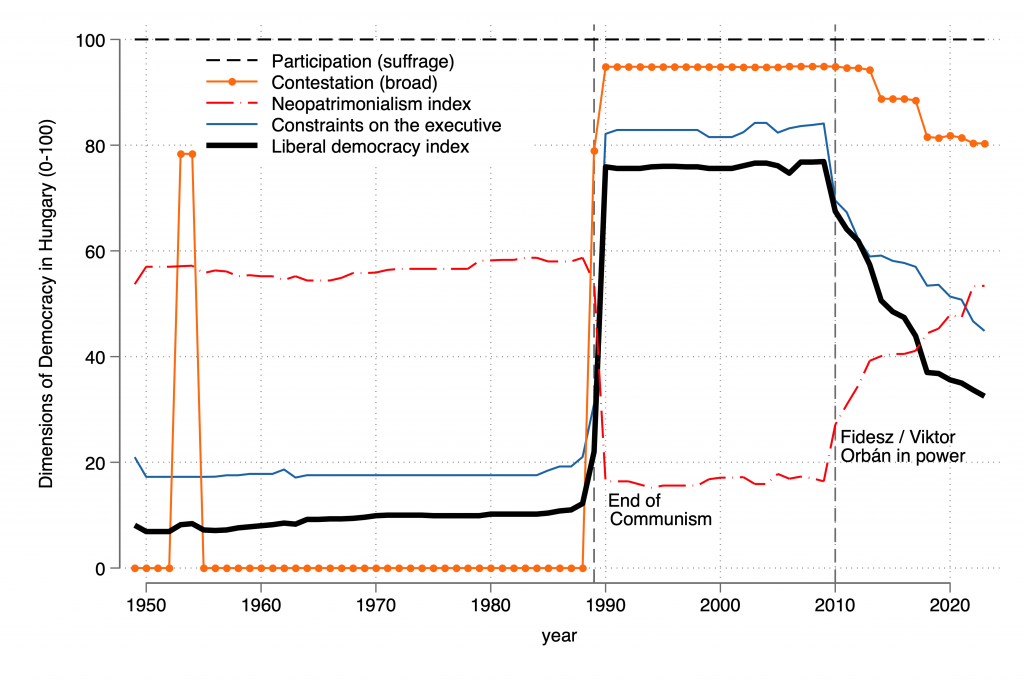

Hungary has experienced severe democratic backsliding and rising neopatrimonialism since 2010, per V-Dem data (see figure below). Among all 42 ongoing episodes of autocratisation worldwide in 2023, Hungary’s is the most pronounced. Poland saw nearly as large a decline in its liberal democracy score since 2015 from a higher start point. In 2019, however, Hungary became the first member of the European Union to ever be downgraded to an electoral autocracy by V-Dem, having previously been downgraded from a liberal democracy to an electoral democracy in 2010.

Orbán exploited the Covid pandemic to seize even more power. In 2022, when Orbán won his fourth straight election – one denounced by experts as less than free and fair – the European Parliament declared that Hungary is no longer a democracy. That year, the European Court of Justice ruled that budget support could be withheld from member states for flouting democratic standards under the 'conditionality mechanism'.

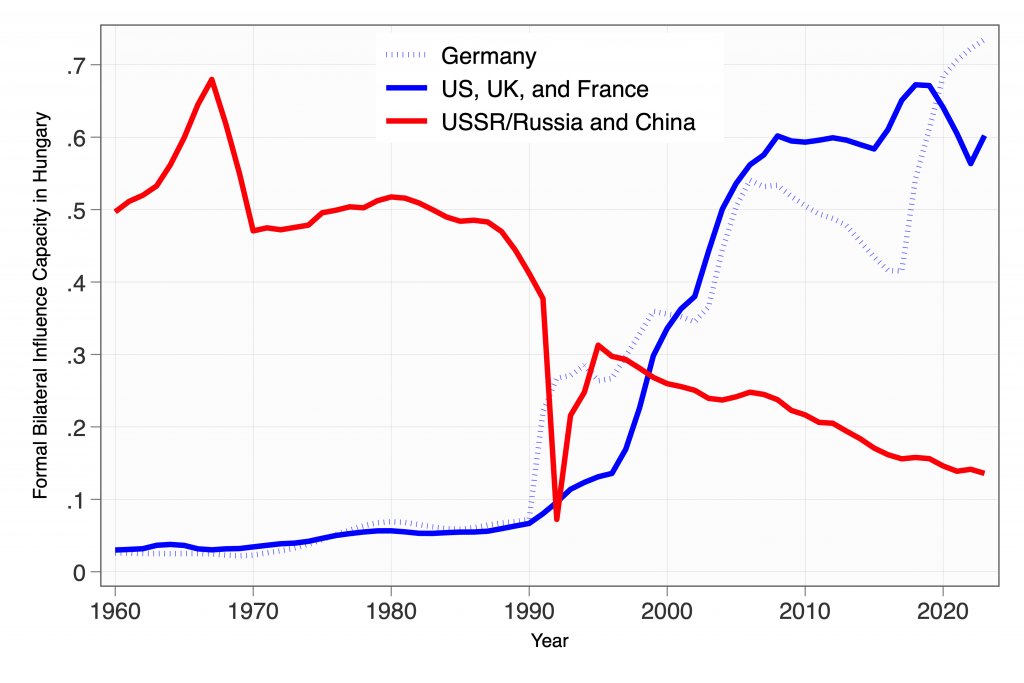

During the Cold War, Hungary was a Soviet satellite, its position in the communist bloc cemented by suppression of the 1956 revolution. According to FBIC data, the Soviet Union had more influence capacity in the country than all other major powers combined. Since 1990, collective Western influence capacity grew continuously until 2010, whereas that of Russia declined precipitously. However, since 2010, western influence capacity (aside from rising arms exports from Germany) has largely plateaued, while China’s economic influence capacity in Hungary has grown, even as Russia’s shrinks:

Orbán is the only standing EU member of what Anne Applebaum calls Autocracy Inc. Other frontline states in central and Eastern Europe from Poland to Moldova have been actively resisting authoritarian sharp power in their countries. But Hungary under Orbán has sought strategic autonomy within Europe and heightened international status – and has therefore invited improved/closer relations with Russia and China.

In contrast with Hungary, other central and Eastern European states have been resisting authoritarian sharp power

Viktor Orbán is Vladimir Putin’s closest ally in the EU. Indeed, he only partially softened his embrace of Moscow after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Hungary dragged its feet for 19 months before approving Sweden’s bid to join NATO last February, repeatedly held up aid for Ukraine, turned itself into a hub for Russian gas, and opposes EU sanctions on Russia. In July, Orbán became the first EU leader to meet with Putin since April 2022. Russian diplomatic influence in Budapest is increasing; Fidesz-aligned media have also spread Russian propaganda and Russian-sponsored disinformation.

Hungary is also 'flirting with China'. Beijing’s influence is growing in Hungary, but from an admittedly low baseline. Hungary is a significant recipient of Belt and Road Initiative investment, with Beijing financing a Eurasian railway connecting Budapest to Belgrade. After expelling the Soros-affiliated Central European University from Hungary in 2018, the Orbán government green-lit controversial plans for China’s Fudan University to build a campus in Budapest. In August, Orbán met with Xi Jinping in Beijing.

It is not sustainable for an EU member like Hungary to simultaneously be a member of Autocracy Inc. Leaders in Budapest and Brussels seem to recognise this. The question, then, is one of geopolitics and values: whose vision will prevail in Europe?

If his latest posts on X are to be believed, Orbán seems confident that the future is with him, Trump, and Europe’s conservative populist nationalists, after years of clashing with liberals in Brussels and the Biden administration.

Yet Orbán’s confidence may be misplaced. Hungary is the first EU pariah, increasingly isolated in the world. Orbán also faces economic and corruption problems domestically, which may help rising political challengers in the next parliamentary elections.