Identifying the individual positions of MPs inside the same political parties is a longstanding problem for political science. Daniel Braby and Marius Sältzer argue that applying automated content analysis to MPs' Twitter timelines can provide a good estimate of sub-party positions

In Europe, parties make the biggest difference in politics. Yet fundamental changes in policy platforms don’t always happen because parties are voted out of office, but rather as a result of parties themselves changing. Leaders get canned, important front-benchers don’t get re-elected, less important back-benchers are replaced by radical alternatives, and so on. Intra-party heterogeneity matters, though academic literature has long neglected it, due to an absence of data sources. But politicians inside parties differ in the same way as parties differ from each other.

Validating positions for individual MPs is an old problem in political science. But it recently got easier to solve, thanks to politicians’ use of social media, notably Twitter. Social media posts, unlike speeches in parliament or legislative votes, are not subject to party control or editorial oversight. They can, therefore, provide us with robust impressions of politicians' positions.

Until now, Twitter data has been used primarily to analyse the electorate. This has led many to declare that Twitter is not real life, in that it doesn't mirror the broader population. But for politicians, Twitter is like a series of online press releases. One overlooked aspect of Twitter data is its ability to reveal legislators' emphasis on specific issues, connectedness to other users, and expressions of preference.

The sheer volume of text requires new, computational methods that allow for the automatic collection and evaluation of text. Here, we provide a brief overview of our novel application for estimating the positions of legislators using Twitter text data. The Academic Twitter API provides for 10 million monthly tweet downloads per project. Using it, we can can ‘scrape’ the account of any MP with a Twitter account, in any legislature.

To understand the relative positions of actors on a common dimension, we need to reduce the political sphere to single continuums for direct comparisons. The process detailed here is partly a methodological note. But it is also a comment on the political frames people often employ to make sense of the complex political world.

Political science has a long tradition of analysing the spoken and written word, mainly because these are the media through which much of politics is played out.

We use saliency theory to establish positions based on the issues on which politicians focus. Traditionally, progressive parties focus on social welfare, while conservative parties focus on law and order. But how can we determine what a tweet is really about?

Content analysis of political text is a large-scale task. Institutions like the Comparative Manifesto Project and the Comparative Agendas Project use an army of hand coders and reliability tests to label the content of sentences. Positions are then commonly estimated based on counts or the proportions of statements fitting within a distinct category.

However, coded manifestos reveal little about the positions of actors within parties, and this is where Twitter can help. Today, 598 of 650 Westminster MPs have an active Twitter account. During a parliamentary session, textual data from Twitter equates to millions of original posts across hundreds of users.

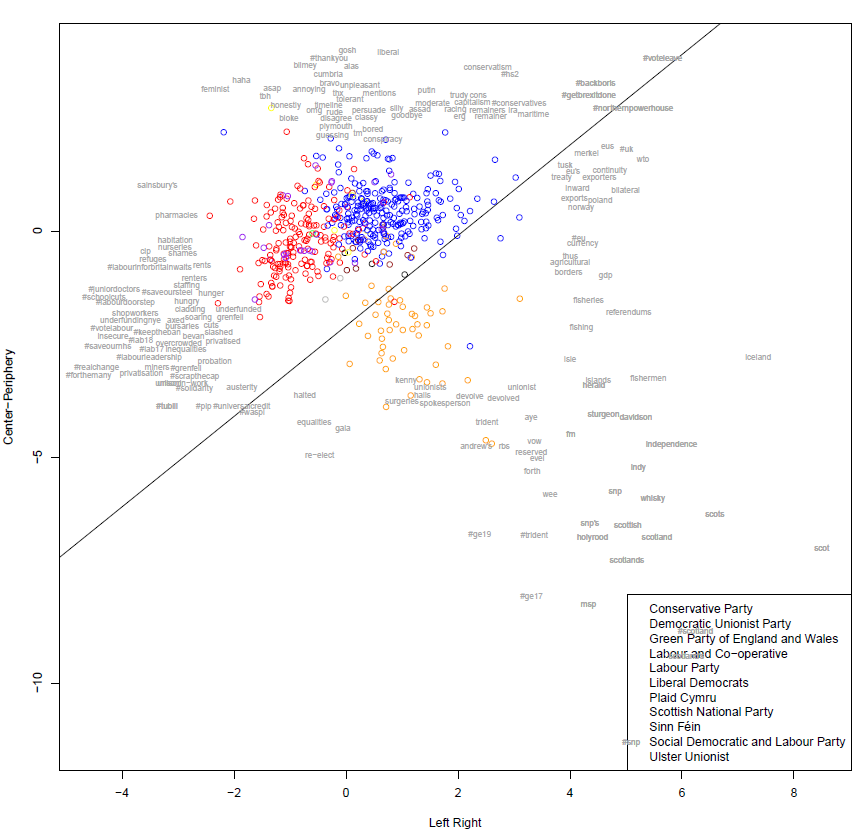

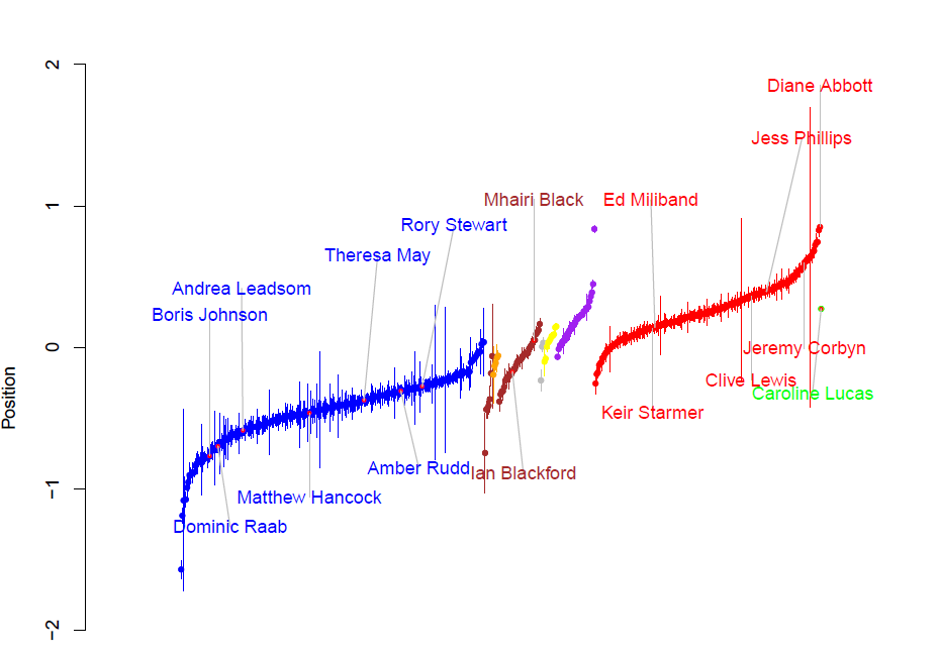

We process Twitter posts, by first removing common and uninformative terms, and group tweets, by usernames. This provides a full sample of each user's original posts within a defined time period. Building on Will Lowe's work on textual scaling methods, we use Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) and visualise our findings using biplots.

CCA is a semi-supervised scaling model with linear restrictions on the solution. It scales terms and documents across multiple uncorrelated dimensions.

In this context, we expect the frequency of words across timelines to differ regarding the policy preferences of political actors. But there are environmental reasons why ideologically opposed actors might share common vocabulary. Members of cross-party committees, for instance, will speak to their common policy expertise. CCA is particularly useful here, because we can control for these environmental associations, for which an unsupervised model would fail to account.

First, we extract the most important dimensions of difference in emphasis. We then choose dimensions that represent ideological diversity, in terms of substantive content and actors' positions.

Next in our ongoing research, we plan to link our estimates to external data sources for validation. So far, we’ve found significant relationships that link Twitter scaling to candidate surveys in Germany, to roll-call voting for the US senate and, more recently, to constituency preferences (left-right self-assessment in the British Election Survey) in the UK.

Beyond examining intra-party heterogeneity, Twitter scaling allows us to plot candidates and politicians along common dimensions. It also lets us observe movement of key actors within fixed time windows. This has vast implications for the literature. It allows us to examine strategic positioning in elections, individual policy-responsiveness in majoritarian systems and, potentially, to predict winning coalitions. See our replication materials

Daniel and Marius present their work on this topic at the 2021 UK PSA Conference, on Monday 29 March. Server to the People: Measuring Dyadic Representation using Twitter