The European Union has faced a long struggle performing alongside its member states on the international stage. States seek other states to deliberate over global issues. Noe Hinck argues that the newly concluded EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement may be the key to changing this status quo

When protectionist measures tore down the structures and assumptions of the rules-based international order, the European Union went on a trade agreement spree. In just five years, from 2014 to 2019, the EU concluded trade deals with more than seven states.

Of these, one relatively unnoticed bilateral agreement heralded a change in the EU's role as a more prominent international player. This is the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (JEEPA) that entered into force in 2019, and it should not be underestimated. Through this agreement, the EU may have found a new instrument to represent itself on the global stage on an equal billing with any other state. More importantly, the agreement allowed the EU to complement, not oppose, the actions of its own member states.

The EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement allowed the EU to complement, not oppose, the actions of its own member states

Since the beginning of negotiations, European and Japanese officials had engaged in intimate, lengthy exchange. This exchange, in the negotiation and implementation phases of the agreement, catapulted EU actors into Japan’s foreign policy orbit. The EU got a chance to familiarise Japan with its institutional complexity. It also revealed its dual personality, whereby it can be its own body yet also represent its 27 member states. This exercise offered a valuable window for the EU to push its agenda for international cooperation.

Japan and the EU have not always enjoyed the supportive relationship they have today. In the 1980s, Japan’s economy boomed. Heavy exports to the American and European markets, which targeted sensitive industries, posed a major threat. Nonetheless, fighting on the same side in the Cold War ensured continuous diplomatic contact. As China rose rapidly to become a top global economy, dynamics shifted in the international system. As they did so, EU-Japan relations took a more cooperative turn.

At the same time, like many other states, Japan didn't quite understand what kind of interlocutor the EU was. Given the EU’s regulatory nature, and Japan’s longstanding diplomatic relationships with individual member states, it made most sense to regard the EU as a partner for trade-related issues. EU member states were considered partners for all other diplomatic matters. Despite the blurry line between trade and politics, anything beyond the European customs union and regulation was deemed a state-to-state issue.

At the EU-Japan summit in 2011, Japan and the EU announced plans for a trade deal. EU competence in this policy domain expected this agreement to be negotiated strictly between DG Trade and Japanese representatives.

But is this a reasonable assumption? A trade deal with one of the world's top economies was naturally also of great interest to all member states.

A Japanese trade deal with one of the world's top economies was naturally also of great interest to EU member states

The trade agreement with Japan also stands out in two ways. First, it is one of two agreements with a G7 state. Second, unlike the agreement with Canada (CETA), negotiations remained out of the political spotlight and influence of domestic party politics on both sides. This allowed both sides to negotiate technicalities, getting to the essence of what both parties wanted out of this agreement.

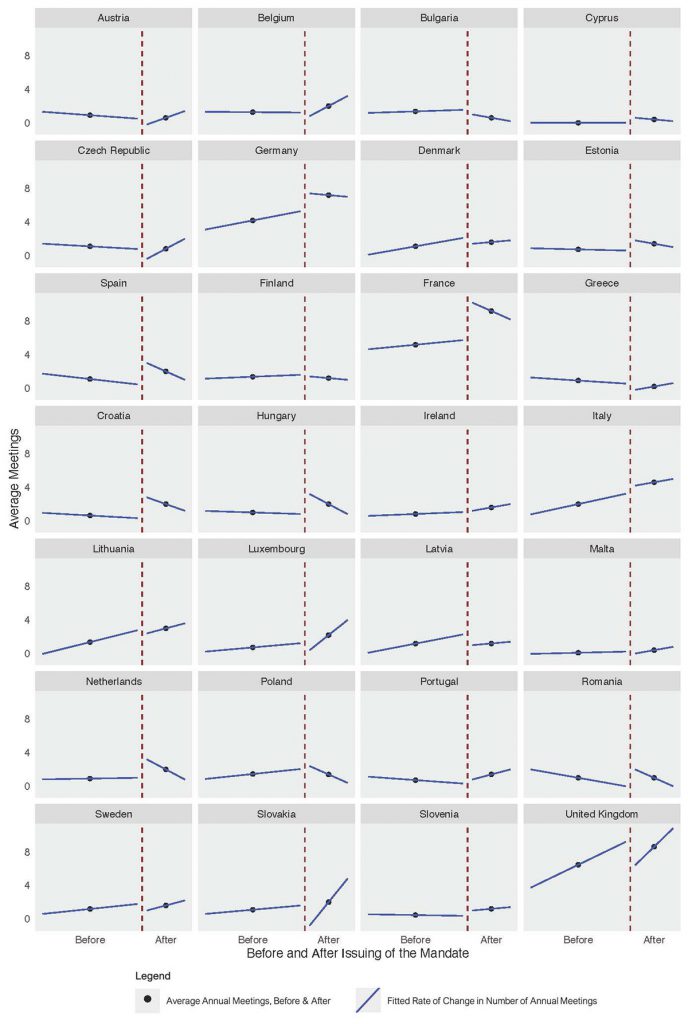

If the EU member states had remained unaffected by the EU-Japan trade talks as they evolved, we should expect to have seen little or no change in the diplomatic exchanges between Japanese and member state officials. Yet, a look at the number of meetings between cabinet members both before and after issuing the mandate (for talks to begin) tells a different story – see the figure below.

We can see that for most member states, the average number of meetings increased after the onset of JEEPA negotiations. (Bulgaria, Czechia, Finland and Greece had little contact with Japan to begin with.) An increase in meetings alone does not tell us much about the reason for their frequency. At most, it indicates there might be a link between trade talks and diplomatic contact.

The content of these meetings reveals more about what the motivation behind them may have been. The Japanese foreign ministry keeps a meticulous record of its diplomatic undertakings. These show that member state officials repeatedly brought up JEEPA negotiations in their bilateral meetings with Japan. Some even discussed sensitive aspects of trade negotiations. These included the import of European beef following the outbreak of Mad Cow Disease, and promising a favourable position on Japan's behalf in European rounds.

EU member state officials repeatedly brought up JEEPA negotiations in their bilateral meetings with Japan

All this shows us that EU member states were indeed involved in the making of the JEEPA. But to what extent their involvement influenced the outcome remains unknown.

The process of dealing with member states and EU representatives in trade negotiations has changed the EU’s image in the eyes of Japan, too. A senior official in Japan’s foreign ministry revealed that the process allowed them to understand better what kind of system the EU is. Japan does not see the EU as a state per se. But it recognises that the EU can be a shortcut to reach all 27 member states, regardless of whether the issue is trade-related.

This changing conception of the EU, thanks to its proven ability to work in unison with its member states, opens new possibilities for the EU on the global stage. The EU’s parallel efforts could habituate the international community to the idea of the EU as a mainstream interlocutor beyond trade. The role of the EU could be enhanced in various non-trade fora where it is already a visible player.

The future of the EU will depend upon effective cooperation and coordination between EU institutions and member states.