The UK government is embroiled in a sleaze scandal after a Conservative Member of Parliament was found to have lobbied for a company in which he held a second job. Simon Weschle argues that these jobs have systematic consequences for how legislators behave in parliament — some problematic, some not

The UK government is under fire after it emerged that some Conservative Members of Parliament (MPs) appear to have inappropriately mixed their second jobs in the private sector with their roles as elected representatives. One MP, Owen Paterson (main picture), resigned after it came to light that he lobbied on behalf of a company that employed him as a consultant for around £100,000 per year. Several other MPs have come under scrutiny too, and there are now widespread calls to ban second jobs. But do they systematically change how MPs go about their jobs as representatives? Or are the MPs that are being discussed right now exceptional, if regrettable, cases?

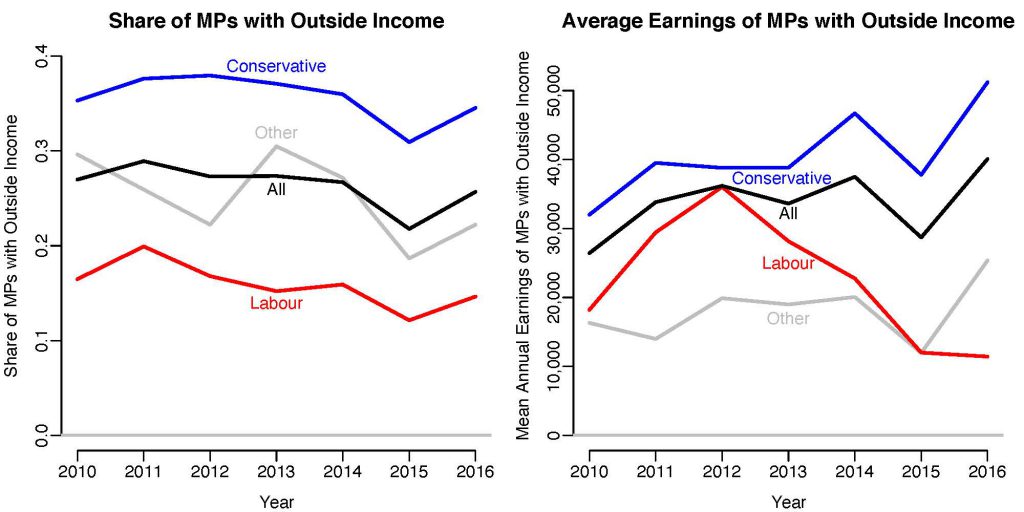

To find out, I collected data on the outside earnings of all House of Commons MPs from 2010 to 2016. My data excludes the Prime Ministers Gordon Brown, David Cameron, and Theresa May. Between 20% and 30% of MPs earned income from second jobs in the private sector. However, there are clear differences between the parties: 30–40% of Conservative MPs had additional earnings, while only 10–20% of Labour MPs did.

Conservatives also earned more in those jobs. In 2016, Conservative MPs who had outside incomes received, on average, more than £50,000 per year. The equivalent figure for Labour MPs was only about £11,500. All in all, Conservatives account for over 75% of all private sector earnings between 2010 and 2016.

Perhaps the most common worry about second jobs is that they influence the content of MPs’ parliamentary activities. To examine whether that is the case, I look at whether MPs' behaviour changes after they take up a second job, and whether they act differently again after they leave their private sector position.

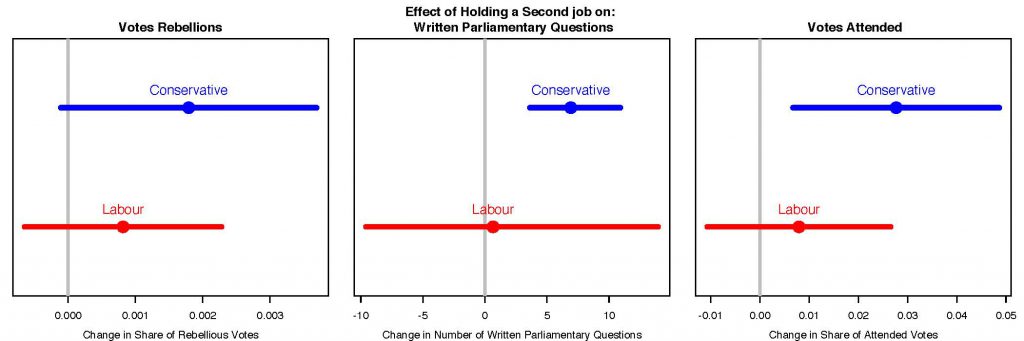

Second jobs have little influence on how MPs vote in parliament. Conservative MPs are about 0.2 percentage points more likely to cast a rebellious vote against the party line when they hold a job than when they do not. This amounts to about one additional rebellious vote every two years, so a small effect. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility that this increase was simply due to chance. For Labour MPs, the effect is even smaller.

However, Conservative (but not Labour) MPs do submit significantly more written parliamentary questions when they hold a second job. These questions are a way for legislators to request information from specific government departments, which are obliged to respond. The median Conservative MP asks 12 questions per year. Having a second job increases this to 19 questions, so almost 60% more.

Conservative (but not Labour) MPs do submit significantly more written parliamentary questions when they hold a second job

This does not need to be problematic. For example, it could be that when MPs have a job, they learn about challenges faced by the industry they work in, and then ask questions to draw attention to them. However, if one digs a bit deeper, it becomes clear that this is not what is going on. First, the increase in questions is largest among MPs in leading company positions (directors and board members). Second, it is especially MPs in knowledge-intensive industries like law and finance that ask more questions. Third, MPs with second jobs target more questions to government departments with larger budgets and more procurement spending. And finally, when MPs work in the private sector, they in particular submit more questions asking for internal information on departmental policies and projects.

the increase in questions is largest among MPs in leading company positions

Thus, the increase in questions when holding a second job is driven by a very specific set of MPs, asking specific questions to specific ministries. This doesn’t mean employers are paying MPs to ask questions. It does, however, suggest that some MPs are influenced by their second job and, consciously or unconsciously, let it affect their parliamentary behaviour. This, in turn, may benefit their employers.

Another common worry about second jobs is that they lead MPs to put less effort into their parliamentary jobs. This is perhaps best exemplified by Sir Geoffrey Cox, who spent part of last year working as a barrister in the Caribbean while participating remotely in parliamentary activity. However, he is an exception: There are no changes in vote attendance for Labour MPs when they have second jobs, and Conservative MPs are about 3 percentage points more likely to attend votes. The main driver of this phenomenon is MPs whose constituencies are located the farthest away from London. Most employers of MPs are located in London. When these legislators get a job, they therefore spend more time in the capital, which gives them more opportunity to be present in parliament. Thus, second jobs need not come at the expense of parliamentary work.

There are no changes in vote attendance for Labour MPs when they have second jobs, and Conservative MPs are about 3 percentage points more likely to attend votes

What are the consequences of second jobs? On the one hand, they do not change which bills become law, and do not reduce parliamentary effort. Neither do they have an effect on the parliamentary questions of many MPs. On the other hand, the targeted increase in questions among some Conservatives is clearly problematic, and raises the possibility that MPs with second jobs change their behaviour in other ways, too.

How one judges these consequences depends on whether one has a glass-half-full or a glass-half-empty outlook on life. Either way, what is clear is that second jobs do not only affect the behaviour of a few MPs. Second jobs have systematic consequences, and any discussion about them should take this into account.

This blog is based on research on Simon’s working paper Politicians' Private Sector Jobs and Parliamentary Behavior.

[…] of accessing official information about MPs’ activities (in particular given concerns about written questions and second jobs) enhances wider legal regimes around money laundering and […]

[…] but that when they stand in Parliament, they may be representing groups beyond their constituents, asking questions (or not asking questions) depending on their outside […]