Back in 2018, Daniel Auer and Didier Ruedin were conducting a research experiment on prejudice in the Swiss housing market. That same summer, a footballer at the FIFA World Cup made a controversial gesture that got the nation talking. After he did so, our researchers observed a significant drop in ethnic discrimination. Were the two phenomena connected?

22 June 2018, the FIFA Football World Cup in the Kaliningrad Stadium. Xherdan Shaqiri has just scored the winning goal in the 90th minute to ensure his team – Switzerland – advance to the last 16. Just like Granit Xhaka who had equalised against Serbia some 40 minutes earlier, Shaqiri forms a double-headed eagle with his hands in celebration. Team captain Stephan Lichtsteiner then joins in.

On 22 June 2018, Xherdan Shaqiri has just scored the winning goal against Serbia, and celebrates by forming a double-headed eagle with his hands – a national symbol of (Greater) Albania

In the following hours and days, an unprecedented debate about this one gesture mesmerises the entire nation. The double-headed eagle symbolises (Greater) Albania. Everyone seems to understand just what it means when players of the Swiss national football team – the sporting pride of the nation – demonstrate allegiance to another country.

A few months later, we ponder over the results of a correspondence test in the Swiss housing market. We and our two colleagues, Eva Zschirnt and Julie Lacroix, had carried this out between March and October 2018. Our team had sent requests to view publicly advertised apartments. We then checked if an invitation was more or less likely depending on the name of the applicant.

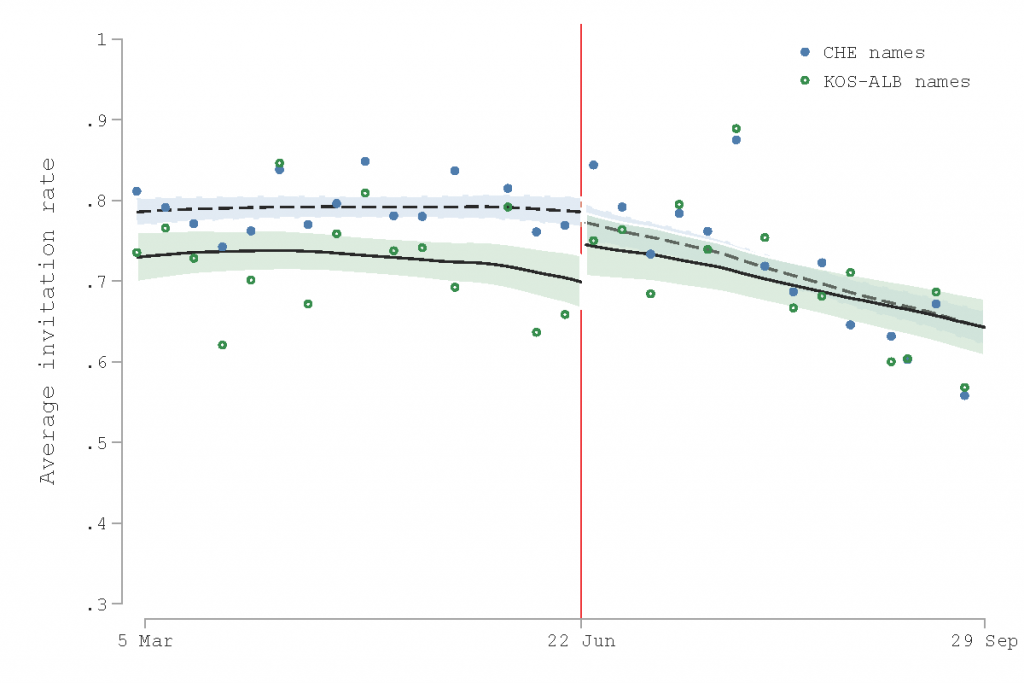

We identified a stark decline in discrimination, to the point that invitation rates for Swiss and Albanian names converged during the summer

As expected, we observed discrimination towards house-hunters with Albanian and Turkish names. But we also identified a stark decline in discrimination, to the point that invitation rates for Swiss and Albanian names converged during the summer. Could there be a World Cup connection?

Using a triple robust difference-in-difference model, we convinced ourselves. The night of 22 June was the turning point, and this sporting event the only plausible explanation for the drop in discrimination. We then spent the following months trying to fill in the gaps and discover the likely mechanisms.

Newspaper archives confirmed what we remembered about that period. There had been a huge spike in commentary and debate after the controversial gesture. In the press, we found a considerable amount of debate about dual loyalties. To what extent can immigrants be loyal to two countries? There was abundant retelling of the players’ origins and their integration as immigrants. There was also speculation about potential sanctions from the governing body FIFA, which does not permit political gestures during games.

Looking at Google search volume, Wikipedia access statistics, and Twitter messages about the players, we established that this was a national debate in which the public readily engaged. We also ascertained that 22 June was the turning-point day. In addition, we established that the three players using the eagle gesture were the specific subjects of attention because of their gesture, rather than as a result of general World Cup coverage.

Notably, the debate remained largely positive in outlook, as our sentiment analysis shows. The public was attempting to make sense of an apparent contradiction. The double-headed eagle is a nationalist symbol of Albania, and Albanian-Kosovan identity. Yet players in the Swiss national squad represent, to a large extent, the essence of Swiss national pride.

In December 2018, the people of Switzerland voted Doppeladler, double-headed eagle, their word of the year. If our evidence on the surprisingly positive tone of the debate needed reconfirmation, this was it. (Over the following two years, the honour was bestowed upon heavyweight words related to climate change and Covid-19.)

On further reflection, we were not only excited about identifying how a single gesture in a football game can reduce discrimination. We also started to realise the implications of our finding.

Existing research presents discrimination and underlying group boundaries as phenomena that change only slowly (if at all). Here, we were demonstrating that rapid changes are, in fact, possible, and that they can be sustained. The experiment ran for three months!

In the longer term we recognise that negative narratives and stereotypes may well counteract the positive impact we describe. However, there could of course be other positive influences that might reduce discrimination.

Celebrities like footballers have significant influence, across age, class, gender, and geographic divisions, in contrast to the often limited reach of sensitivity campaigns

And such influences, of course, can be brought to bear. Celebrities (such as members of a national football squad) have significant influence, especially during major sporting tournaments. They tend to have broad appeal and the ability to reach out to a range of people across ages, class, gender, geographic and other social divisions.

People are interested in celebrities, and are unlikely to choose not to be influenced. Sensitivity campaigns, however, often struggle to communicate with new audience groups, and end up preaching to the converted, so to speak.

Policy makers would be well advised to draw a lesson from advertising. This industry uses celebrity role models to boost sales of a huge variety of consumer products. The results of our experiment (one that came about by sheer coincidence) suggest that celebrities can also sway – from a societal perspective – public attitudes on fundamental social issues. As researchers, we will certainly pay more attention in the future to role models and celebrities, and the ways in which their actions may help counter discrimination.

This blog post is based on the authors' recent article in the European Journal of Political Research

[…] Blog at The Loop […]