Native speakers of Catalan and Basque are important to voting and political culture in Catalonia and the Basque Country. Yet, argues Rubèn Llorens Poblador, there are clear differences in the two cases. The Catalan parliament registers a deeper language-based voting gap, as evidenced in the recent regional elections

'Nation builders' usually care more about language than any other components of identity. Not surprisingly, therefore, nationalists from all continents have put their efforts into establishing so-called 'national languages'. Despite this, homogeneous linguistic landscapes are rather uncommon. Spain, which scholars often depict as an example of an unfinished nation-state, knows this very well. Calls for Basque and, especially in the last decade, Catalan independence, have travelled around the world.

Basque and Catalan nationalism have a tradition dating back to the late 19th century. At inception, their ideologists, like all nation-builders, had to decide which core values to emphasise.

The first Catalan nationalists resolved that language was the main link to national identity. Citizens in Catalonia approved of this because the Catalan language had a strong social presence at the time. Additionally, Catalanism has its roots in a movement of cultural revitalisation known as La Renaixença.

In contrast, Sabino Arana, the father of Basque nationalism, played down the importance of language, emphasising instead the ethnicity of the so-called 'Basque race'. In fact, in the nineteenth century, Basque was considered no more than a useful ethnic boundary. Indeed, diglossia, in which a community uses two languages under different conditions, was much more prevalent in the Basque Country than in Catalonia. The local elite reinforced this with its lack of 'linguistic loyalty'.

When national movements first emerged, the Catalan and Basque languages enjoyed different levels of health, even if both were considered to be 'second-rate languages'. Catalan – which was the more widely spoken of the two minority languages, even in urban areas – was not abandoned entirely by the local elite. Speaking Basque, on the other hand, signified one had no desire for social climbing.

Today, Catalan and Basque are both official languages in their respective territories, alongside Spanish, which is the official language across all of Spain. However, only 36.2% of the Basque Country’s population speak Basque and only another 18.6% understand it. This means that nearly half the Basque population does not understand or speak the local language at all.

In contrast, 81.2% of Catalonia’s population can speak Catalan and only a few (5.6%) are unfamiliar with the language.

In Catalonia and the Basque Country, the Spanish language always prevails. However, the disproportion between native speakers of the minority linguistic groups and Spanish is much greater in the Basque Country, where around three-quarters of the population has Spanish as their only native language. The same is true for the social use of each language, which is more balanced in Catalonia.

In both cases, native speakers of the local language identify strongly with a predominantly local identity. However, the correlation between having Spanish as one's native language alongside a predominantly Spanish identity is much stronger in Catalonia. Spanish is more of an autochthonous language in the Basque Country, which makes the gap in ethnolinguistic identity far more evident in Catalonia.

So, paradoxically, Catalan does not divide the population in terms of linguistic abilities quite as much as Basque does. It does, however, seem to be more divisive regarding identity. According to data from regional elections in spring 2024, this fracture seems to be more important in terms of voting, too.

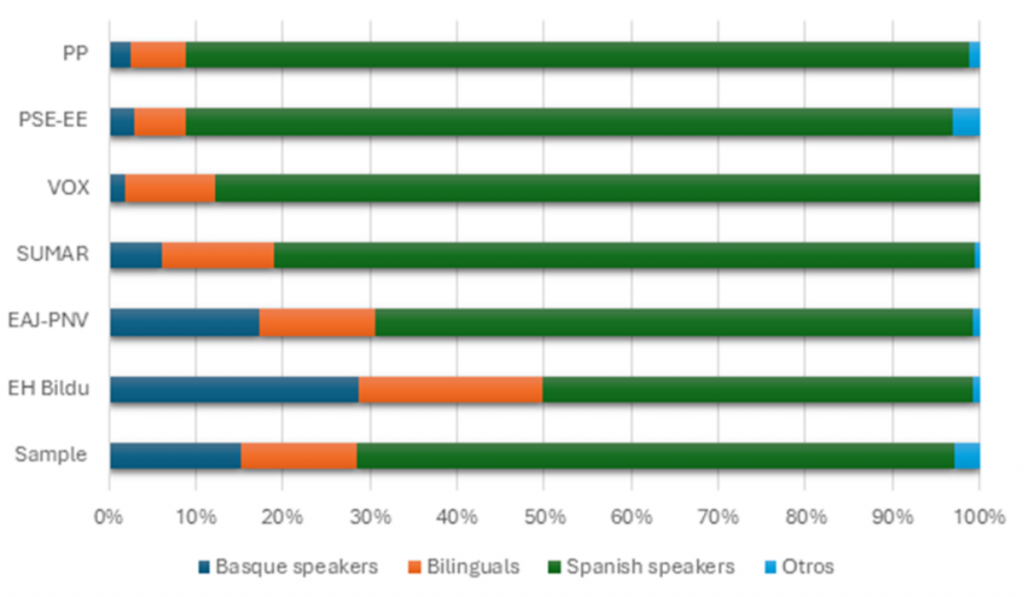

Basque speakers and Spanish speakers are either overrepresented or underrepresented – compared with their proportions in the general population of the Basque Country – in each party’s electorate. However, this disproportion is not too significant in comparison with the Catalan party system.

Catalan does not divide the population in terms of linguistic abilities quite as much as Basque does, but it seems to be more divisive regarding identity

Undoubtedly, Basque native speakers are overrepresented in the electorates of Basque nationalist parties’ electorates – significantly more in the case of EH Bildu than in that of EAJ-PNV – and underrepresented in the others.

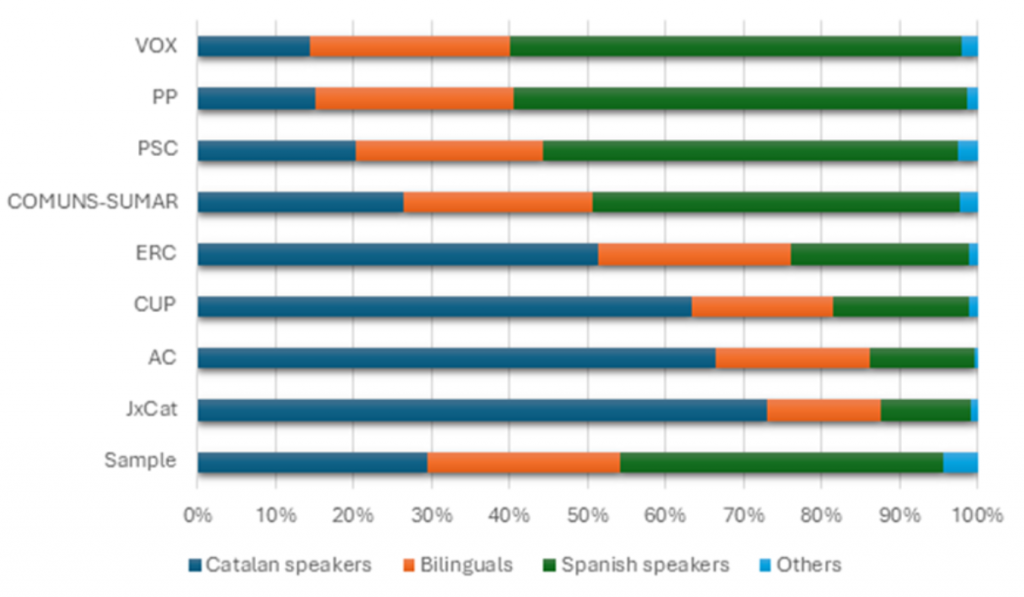

A similar divide exists in Catalonia, where Catalan nationalist parties attract predominantly Catalan-speaking electorates and state-level parties predominantly Spanish-speaking electorates. Yet, the language gap in Catalonia is much deeper than it is in the Basque Country.

First, language is a core value for Catalan nationalism to a greater extent than it is for Basque nationalism. This suggests that, in Catalonia, language should be more divisive in terms of identity voting. Researchers have found, for example, that Catalan nationalist MPs care much more about language than their Basque counterparts.

Research shows that Catalan nationalist MPs care much more about language than their Basque counterparts

Second, the rise of secessionist ambitions in Catalonia over the past 15 years has polarised the region's party system on the national-identitarian cleavage, and this has led to the configuration of two large opposing blocks. Meanwhile, polarisation has been decreasing in the Basque Country, where pro-independence terrorist violence no longer exists.

Finally, from a more pragmatic perspective, Catalan is a native language for a much larger proportion of Catalans than Basque is in the Basque Country. This imbalance is thus more likely to produce a language gap in the vote.

In other words, why would Basque parties seek votes from those who speak only Basque? It just wouldn't be worth their while.