Ruth Dassonneville, Stephen Quinlan and Ian McAllister go beyond the conventional wisdoms about women in politics to explore how the public views women leaders. Their findings suggest that women are more popular leaders than men, but less successful in translating that popularity into votes

In 2017, Hillary Clinton published What Happened, a memoir about her experiences as the Democratic Party's presidential candidate in the 2016 election. In it, she observed,

‘It is not easy to be a woman in politics… it can be excruciating, humiliating. The moment a woman steps forward and says "I’m running for office", it begins: the analysis of her face, her body, her voice, her demeanour; the diminishment of her stature, her ideas, her accomplishments, her integrity. It can be unbelievably cruel’.

Extract from What Happened by Hillary Clinton

Clinton’s views represent the accepted wisdom about women in politics. But how does the public view women political leaders? Do they consider them to be less effective and worthy of support than men?

The research into how voters view women and men leaders has come to mixed conclusions. There is some evidence that the public uses gender stereotypes to evaluate female candidates. For example, women are characterised as kind, helpful and caring. Voters don't tend to associate these traits with the image of a strong leader, who should exercise authority and make difficult decisions.

This is also reflected in how the mass media treats women candidates. For example, the media often portrays women in the context of their families, something that occurs less frequently with men.

the media often portrays women in the context of their families, something that occurs less frequently with men

Despite this, the research that has examined whether voters appear to discriminate between candidates based on their gender produces little evidence that such treatment of women in politics comes with an electoral cost. Women candidates may not get elected but it is not usually because of their gender. Indeed, there is some evidence that women candidates may actually get more votes than their male counterparts.

Existing research, however, has been based on election candidates, often those competing at the local level. Moreover, the bulk of the evidence comes from advanced democracies, often with a specific focus on the United States. The results might therefore not generalise beyond these limited case studies.

To test whether women in politics are less popular than men, we examined leaders rather than candidates. If discrimination exists, we are more likely to find it among leaders, because electorates hold leaders to higher standards than they do candidates. Moreover, in principle, the media attention that leaders attract should mean that voters have more information with which to reach an evaluation.

We also used an unprecedented database – the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Integrated Module Dataset. The dataset used here has over 150,000 respondents and covers 487 leaders across 46 countries.

We collected information not only on leaders' gender, but on their age and length of time as party leader. We also wanted to know whether they had previously held executive office.

From this vast database we found that the frequency of women party leaders increased from 11% in the late 1990s to 17% in 2011–16. We also find that women leaders, on average, are younger than their male counterparts, have less executive experience, and likely to have been leaders for a shorter period.

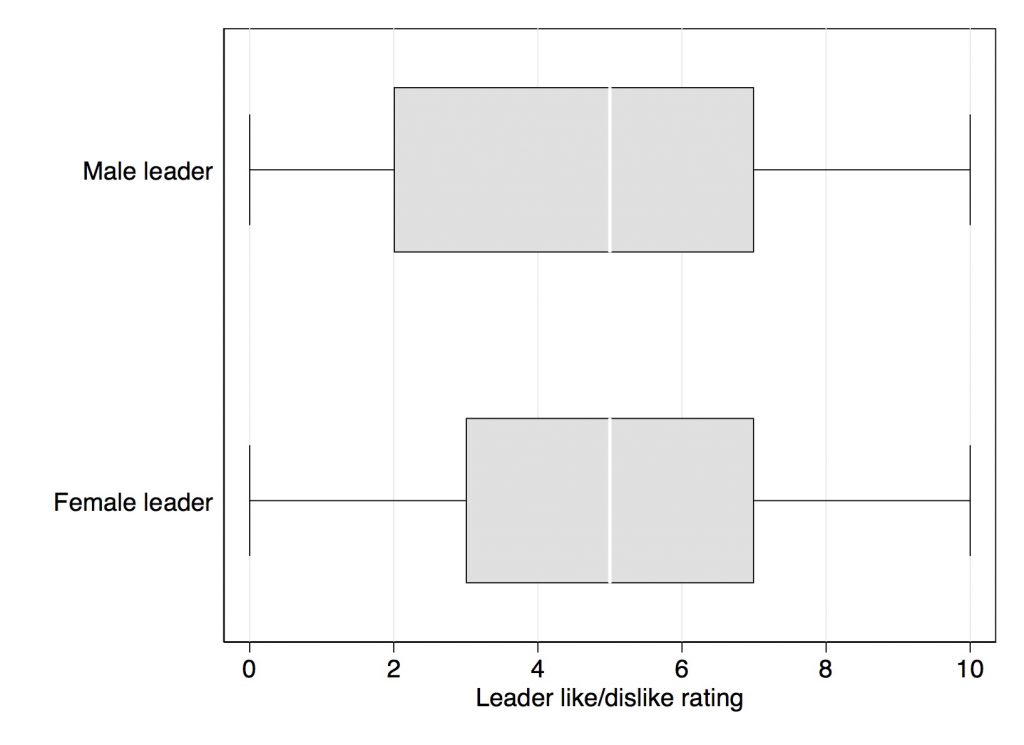

The evidence is based on a question which asked survey respondents to rate leaders on a scale from zero (least liked) to 10 (most liked). From this measure we found that women leaders were more liked than male leaders. The mean score for a male leader was 4.4 compared to 4.8 for a female leader. That difference in means is driven by there being more male than female leaders who are not liked much. See the box plot below.

This difference suggests that voters' perceptions of male leaders might be partly influenced by the fact that they headed relatively unpopular parties.

To account for such party-level differences, we conducted a further analysis, including party and political experience. Taking these additional factors into account did not affect our conclusion that women leaders are more popular than men. We also found that women who had prior executive experience were significantly more popular than men.

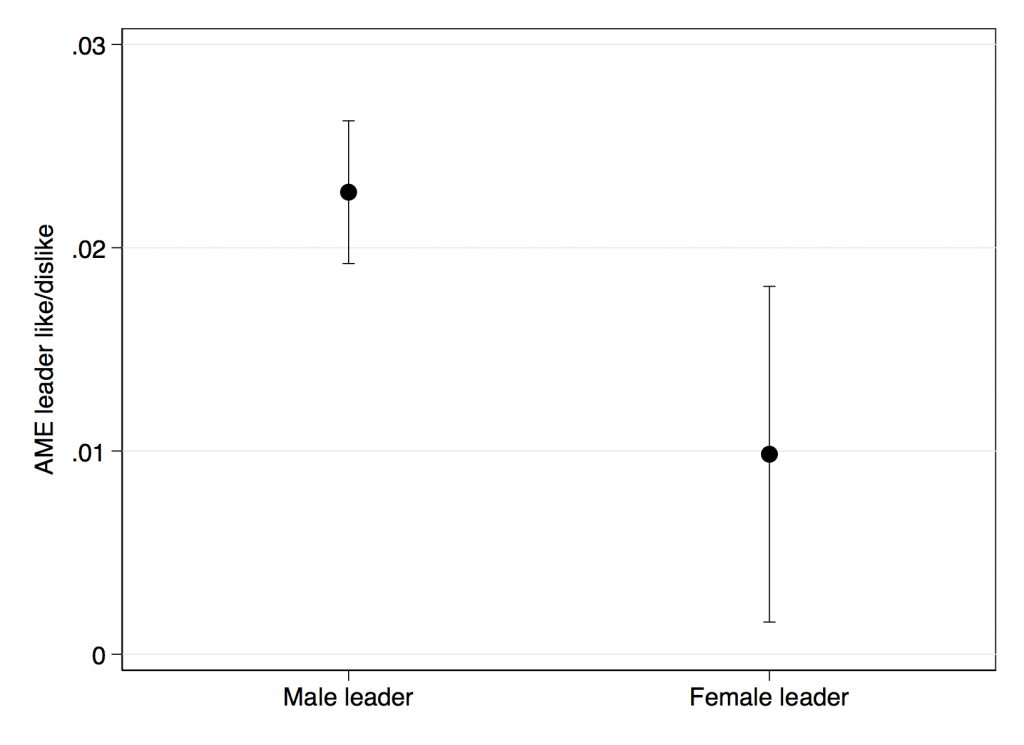

With the increasing personalisation of politics, leaders matter for elections. We might expect, then, that more popular female leaders would garner more votes for their party. Our results did not show this. In contrast, we found the likeability of a woman leader was less critical in shaping the vote than for a man, net of other things.

The figure below puts this in perspective. It shows that the impact on the vote of an increase in popularity for a woman leader is about half that for a comparable male leader. In other words, women are less effective than men in translating their popularity into votes.

What accounts for this counterintuitive finding? Our analyses ruled out effects associated with less executive experience or party size. While we were unable to identify the cause, our findings suggest there remains some element of discrimination against women in politics, despite their greater popularity when compared to men.

there remains some element of discrimination against women in politics, despite their greater popularity when compared to men

As the representation of women in politics grows, questions of leadership, popularity and women's ability to win elections will increase. Our results show that women are more popular than men, but less effective than men in translating that popularity into votes. One explanation is that stereotypical views of women as caring and compassionate may lead to higher likeability.

Still, voters want to see traits such as strong leadership and authority in those they elect to office. Future research needs to tease out this remaining puzzle.

This blog is based on the authors’ 2020 European Journal of Politics and Gender article Female Leader Popularity and the Vote, 1996–2016: A Global Exploratory Analysis