Dictators depend on committed bureaucrats to stay in power. To instil loyalty, some indoctrinate through enforced military service. Alexander De Juan, Felix Haaß, and Jan Pierskalla argue that this strategy can backfire. Rather than creating truly convinced cadres, conscription can help bureaucrats get better at faking loyalty

From the perspective of autocratic leaders, civil servants are a critical segment of the population. Clerks, accountants, commissioners and administrators don't just form the backbone of regime support; they are also responsible for implementing the regime’s policies. But how do dictators cultivate loyalty among their regime apparatus?

Forced military service can be a cost-effective tool to achieve the loyalty of bureaucrats. It provides a controlled environment for implementing political ‘education’ that also conveys a coherent political ideology.

For example, in the early 1980s, in the Soviet Union, 90—100 minutes of a conscript’s workday were devoted to political work. This included regular tests on the content of the political training. Based on this logic, we would expect conscription to increase cadres’ loyalty and effort.

military service provides a controlled environment for implementing political ‘education’ that conveys a coherent political ideology

Our research explores this proposition in the context of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). The GDR (1949—1990) is a useful case because of its large administrative apparatus and the comprehensive and hierarchical socialist cadre system. Also, the GDR only introduced conscription relatively late, in 1962. This allows us to compare cadres before and after the introduction of conscription.

Political indoctrination during military service in the GDR was intense. Based on historical sources, we estimate conscripts were exposed to between 600 and 1,000 hours of political ‘education’ during their 18-month service.

We wanted to understand whether this intensive political indoctrination created a more committed bureaucratic workforce. Our research is based on a rich historical dataset of over 370,000 electronic cadre files collected by the socialist regime: the so-called Central Cadre Database. The regime created this database to facilitate socialist planning and allocation of staff, originally storing the files on huge magnetic tapes. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the German Federal Archive obtained and digitised these files, allowing us to create a panel dataset with over 3.5 million cadre-years.

There are two challenges in identifying the causal effect of military service — and indoctrination within the military — on bureaucrats’ system engagement. If military service is voluntary, it might be the particularly loyal recruits who choose to join the military in the first place. But if military service is mandatory, there is no obvious comparison group to check whether the service had any effect, since everyone has to join.

To overcome this challenge, we rely on a historical quirk. The GDR introduced mandatory conscription only in 1962, several years after its founding in 1949. This late introduction allows us to compare conscripted cohorts with non-conscripted cohorts before and after introduction of the conscription law.

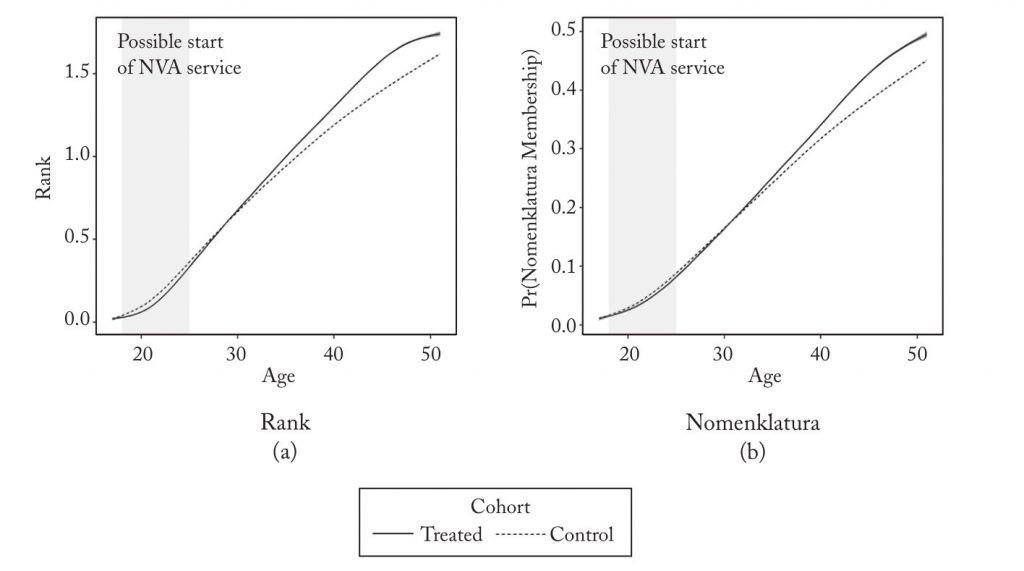

Measuring system engagement through cadres’ career advancement, i.e. rank in the nomenclature and belonging to the nomenclature, we find that conscription did indeed increase system engagement in the GDR cadre system. In the figure below, we see that cadres who underwent conscripted military service (the ‘treated’ group) outperform non-conscripted cadres in nomenclature rank and membership during the later years of their careers.

Does that mean that conscription worked as an instrument for indoctrination? No, probably not.

Probing the data further, we find several pieces of evidence which suggest that the mandatory military service — and its political indoctrination — allowed recruits to fake outwardly loyal behaviour rather than creating truly committed cadres. It's a phenomenon the economist Timur Kuran calls 'preference falsification.'

rather than creating truly committed cadres, mandatory military service allowed recruits to fake outwardly loyal behaviour

First, we find that conscripted cadres join system-relevant socialist organisations, such as the German-Soviet Friendship Organisation, more frequently. But conscripted cadres are less likely to engage in voluntary functions, such as treasurer or spokesperson, within those organisations. This runs contrary to what we would expect from cadres particularly convinced by socialist ideals.

Second, once conscripted cadres reach a higher position in the nomenclature, they engage less in these socialist organisations. Again, this isn’t what we would expect from particularly convinced socialists.

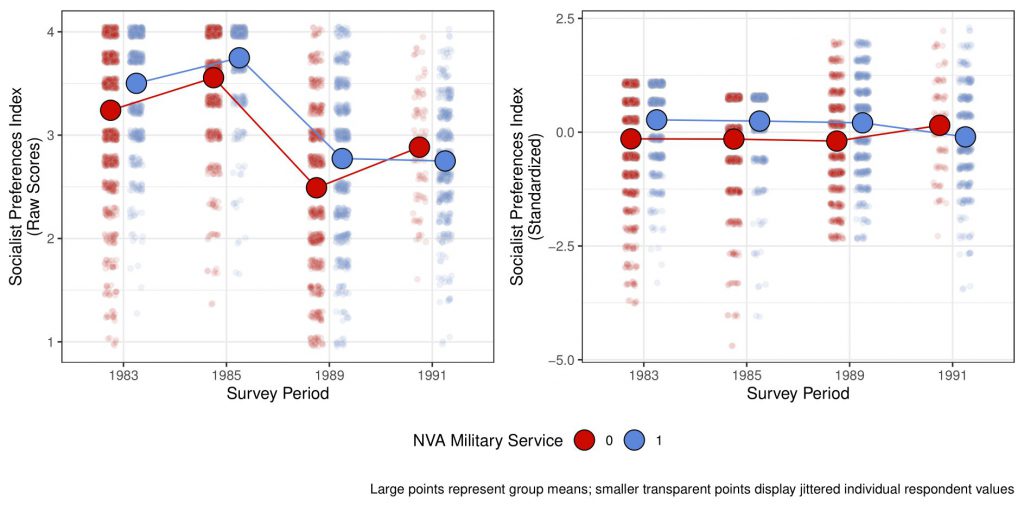

Finally, historical surveys indicate that cadres who served in the military were particularly likely to display strong socialist convictions before the fall of the regime. After 1989, however, they display decidedly lower socialist preferences than individuals without a military service history.

Military service equipped recruits with a better sense of what socialist interviewers wanted to hear. Only after 1989, when revealing one’s true opinion to interviewers was safer than during socialist rule, were true preferences voiced.

This finding should simultaneously give us hope, but also a reason for caution. Given the intensity of indoctrination in the GDR, the evidence we find for preference falsification highlights civilian resilience against indoctrination.

evidence for preference falsification shows how civilians can resist indoctrination

At the same time, our finding also highlights the role of opportunism in the bureaucracy that might help the regime remain in power — for a time. This opportunism creates an information problem for autocrats: they can’t really know whether indoctrination worked or not. If preference falsification is widespread, most cadres behave in line with regime preferences. In moments of crisis, however, such behaviour can backfire.

Faced with actual threats to the regime, in the form of sustained protests or mass uprisings, bureaucrats who only fake ideological conviction might not be willing to aid the regime in repressing the population. This, ultimately, can lead to a regime's downfall.

This blog piece is based on research in the authors' recent World Politics article, The Partial Effectiveness of Indoctrination in Autocracies: Evidence from the German Democratic Republic

Putin maintains bureaucrat loyalty by providing wealth and job security. Plus the threat of falling from the top floor of a multi-story building for unwanted behavior.