Decarbonisation requires a shift in climate governance focus, from the international to the domestic, writes André Luiz Campos de Andrade. At the domestic level, local, regional, and national governments must join forces to achieve their climate targets

The Paris Agreement and its main implementation and transparency instruments continue to progress at a global level (e.g. Long-Term Strategies, Paris Agreement Rulebook). In this context, concerns about humankind's ability to address climate change in a timely manner have come into sharp focus. The capacity of countries to effectively implement their commitments (Nationally Determined Contributions) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is under particular scrutiny.

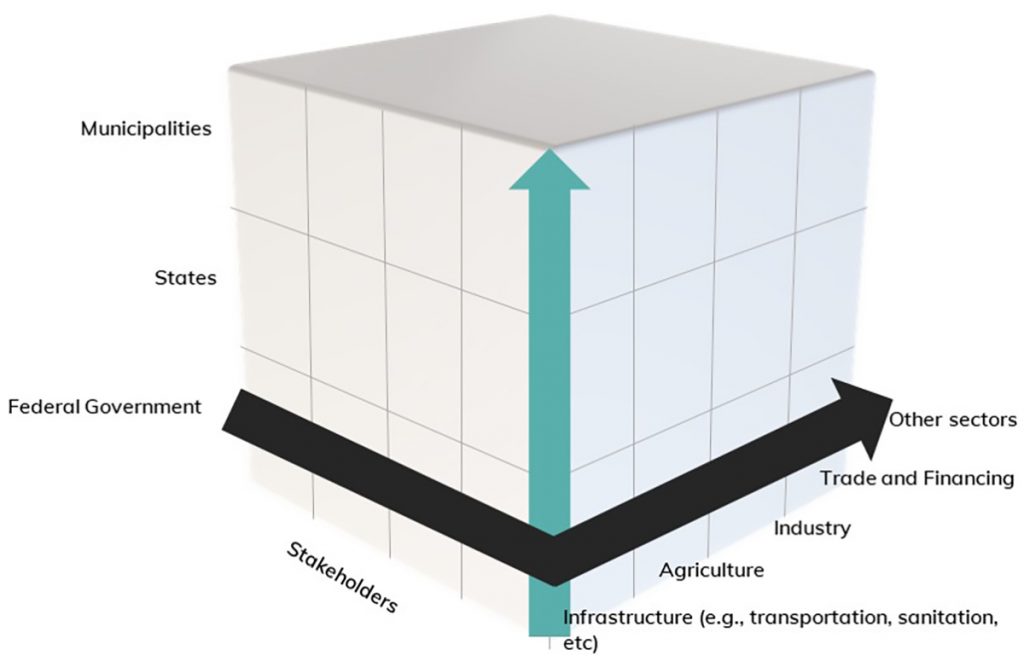

Effective multilevel climate governance at the domestic level is key. Multilevel governance refers to the 'mutually dependent relationships – be they vertical, horizontal, or networked – between public actors situated at different levels of government'. In climate policy, we see this approach involving different economic sectors:

We also need to see more ambitious commitments from countries under the Paris Agreement. These remain far below the efforts required to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius beyond pre-industrial levels. The same applies for the need to scale up adaption measures globally. Climate governance is an important enabling condition for both tasks.

Focusing only on environmental ministries overlooks, for example, that emissions come from all economic sectors

Yet, building effective climate governance at the domestic level is not an easy task. The difficulties faced by developed and developing countries in achieving their goals confirm this. In general, the management and leadership of climate policy sit under the umbrella of the countries' environment ministries.

We should not dismiss the importance of environmental areas within climate governance. But focusing only on environmental ministries overlooks the multi-level and multi-sectoral perspective required for a climate policy to mitigate and adapt countries to climate change.

In most countries, sources of greenhouse gas emissions are dispersed across different economic sectors. They go beyond the institutional jurisdiction of the environmental policymaker. This tends to impose difficulties for an effective climate policy.

Climate policy faces different challenges throughout its domestic cycle of agenda formation, formulation, decision-making, implementation and evaluation. We can group these challenges into four categories:

Political challenges are related, for example, to political and economic groups' opposition to the necessary structural transformations for decarbonisation.

Institutional challenges are related to the fragmentation of bureaucratic responsibilities in the execution of different governmental policies and programmes relevant for mitigation and adaptation. They also relate to the impact this has on harmonisation, coherence and integration of climate action within the country. Besides this, there are institutional bottlenecks in designing the right mechanisms and instruments to coordinate climate policy well.

Challenges in the realm of resources include financial and budgetary constraints which prevent investments in mitigation and adaptation projects. Moreover, the several governmental agencies at all levels, national and subnational, responsible for relevant actions may suffer a different resource constraint: an absence of personnel with technical expertise in climate science.

Lastly, there remain informational and scientific challenges. These relate to data, studies, and monitoring systems. Such tools help the whole decision-making process and the implementation of climate policies and actions.

The intensity of these challenges tends to differ from nation to nation. It's worth comparing such challenges with national characteristics outside climate policy, including income and wealth levels, political-administrative organisation, governmental regime, and whether or not a country is a functioning democracy.

Climate policymakers may have little or no control over the challenges they face, but must still consider them

Climate policymakers have little or no control over these factors. However, policymakers must consider them equally so that countries can achieve their climate ambitions and build a sustainable, healthy future for our planet.

The 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment was a milestone for the integrated discussion of environmental and economic development. Fifty years later, authorities and leaders from around the world will gather again in Stockholm this June for the Stockholm+50 Conference. But they won't just be celebrating the half-century anniversary of the first conference. The international community will also discuss the routes necessary to ensure a more sustainable future for our planet.

This meeting is vital because it comes at a moment of crisis that affects our planet in many different ways. Climate. Biodiversity loss. Pollution. All are key issues. Stockholm+50 takes place against the backdrop of the need to bring about a green recovery in a post-Covid world. What's more, we have only eight years left to achieve the UN's 17 sustainable development goals.

Many of the problems we face are caused directly by a lack of multi-level climate governance

At the end of the June conference, it is essential that participants make political reference to the need for countries to structure their climate policies on a multi-level, integrative governance model. This will offer better planning and implementation conditions for the various governmental policies and programmes relevant to climate change mitigation and adaptation. It will also bring co-benefits to the other actions under the 2030 Agenda.

Over the last fifty years, we have learned that thinking about multi-level climate governance from a domestic perspective is key to solving the climate crisis. In fact, many of the problems we face are caused directly by a lack of multi-level governance. This vision must guide world leaders' conversations, and inform the final declaration of Stockholm+50. We do not have another fifty years to fine-tune our climate governance.