In recent decades, women across the globe have entered parliaments in greater numbers. Few of them, however, end up as senior MPs with long experience. This, write Ragnhild Louise Muriaas and Torill Stavenes, means that women – even in advanced democracies – continue to hold much less parliamentary power than men

Conditions for democratic representation are deteriorating in many countries, as the foundational piece in this series makes clear. Still, if we look at gender balance in a slightly different way, the situation for male and female parliamentarians is not particularly equal, even in the most equal-looking established democracies.

Of course, women make up nearly 50 per cent of parliamentarians in countries such as Spain, Norway, and Sweden. But does that mean that gender parity in the parliamentary arena has finally been achieved? No. Not even in numbers.

For countries with a healthy percentage of women parliamentarians, has true gender parity been achieved? No. Not even in numbers

Being present in a parliament is one thing. But reaching positions of power – shaping the political agenda or simply being able to push through policy – are entirely different. To achieve the latter, we know that experience, authority and networks are crucial. These advantages are achieved primarily by those who have served several terms in a parliament: the senior MPs. So even if the descriptive gender balance is improving, the level of gender balance in seniority – even in advanced democracies with healthy democratic structures – is low. And it is clearly skewed towards men.

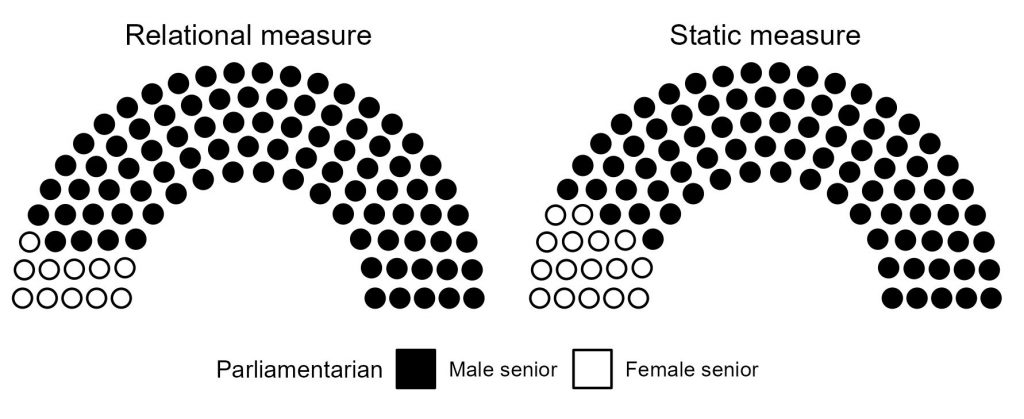

Our research analysed parliaments across nine advanced Western democracies – Ireland, the UK, Canada, the US, Spain, France, Germany, Norway, and Austria – between 1965 and the present day. For the first time, we show that significant gender gaps exist among the MPs with the longest experience. And even if we measure gender gaps in different ways, the results remain the same. Among MPs who have served three or more terms (static measure), an overwhelming majority – 84% – are men. By comparison, women comprise only 16%. The gender gap is thus a significant 68 percentage points.

Gender distribution among seniors on the relational and static measures, all countries, 1965–2020. Seniors on the relational measure are MPs serving five or more terms; four terms denote the 75th percentile in the full data set (across all years).

Source: Comparative Legislators Database

This gap is even more substantial if we look at the 25% of MPs with the longest tenure in any given country (relational measure). 89% are men, and just 11% women. This reveals a staggering gender gap of 76 percentage points.

Of the 25% of MPs with the longest tenure between 1965 and 2020, 89% are men, and only 11% women

Finally, our research demonstrates how gender gaps in seniority increase with the number of terms served in parliament (continuous measure). In the nine European countries analysed, 52 percentage points separate the number of male and female MPs serving two terms in parliament. However, for seniors who have served nine terms, the gender gap stands at 90 percentage points in favour of men. Our overall findings show how in contemporary parliaments, women remain disadvantaged, and still hold less power than men.

Since 1965, the earliest year of our data material, women have made great strides towards equal representation. Not only has this occurred in the political arena, but also in business and in the labour market. In Norway, the percentage of female MPs in parliament has increased from 15.5% in 1973 to almost 45% today. That said, in the US the proportion of women politicians in the House of Representatives stands at only 29%. The Irish Dáil has an even lower share of women: just 23%.

Our research found that even in countries which have long enjoyed gender-balanced parliaments, the gender gap in seniority persists

There is also a corresponding link between the proportion of women in parliament and the proportion of female seniors. The gender gap in seniority decreases over time – especially in certain contexts. Nevertheless, even in countries that have long enjoyed gender-balanced parliaments, the gender gap in seniority persists.

In Norway, the gender gap in 2020 stood at 10 percentage points, down from 80 percentage points in the 1980s. Spain has managed to decrease its gender gap from 80 percentage points around 1990 to 20 percentage points in 2020. And alhough Austria’s parliament has a 40% female share, its gender gap in seniority remains around 50 percentage points.

In Ireland, we find drearier results. The country's gender gap in seniority was still over 90 percentage points in 2020, down only slightly from nearly 100 percentage points back in the 1980s. The UK fares a little better. It has managed to decrease the gap from the same level as Ireland in the 1980s to just above 70 percentage points today.

What is striking, therefore, is that women’s power in parliaments, understood on the basis of their accumulated seniority, was, and remains, much lower than men's. Women simply do not persist long enough in parliaments to acquire the same experience and benefits as men.

Newcomers are more likely to receive critical comments in parliament, more likely to toe the party line, and less likely to rebel against the party leadership. Given all this, the gender gap in seniority appears even more dramatic. To remedy the persistent marginalisation of women in politics, we need to look beyond merely the number of women in the legislative assembly. Rather, we must make sure that women stick with politics for longer, until they enter the senior ranks.

No.11 in a Loop thread on Gendering Democracy. Look out for the 🌈 to read more in this series