France is removing Comorian migrants from its overseas department of Mayotte. Yacine Ait Larbi argues that this is a dangerous approach. Policy-making, he says, should be sensitive to global change and, especially, to the impact of colonisation on communities across borders

Nearly 80% of the population of the island of Mayotte, a French overseas department since 2011, lives below the poverty line. Recent rhetoric from the Ministry of Interior laid the blame for the island's hardships squarely on immigration. The French government's Operation Wuambushu is thus aiming to displace Mayotte's so-called 'irregular' residents.

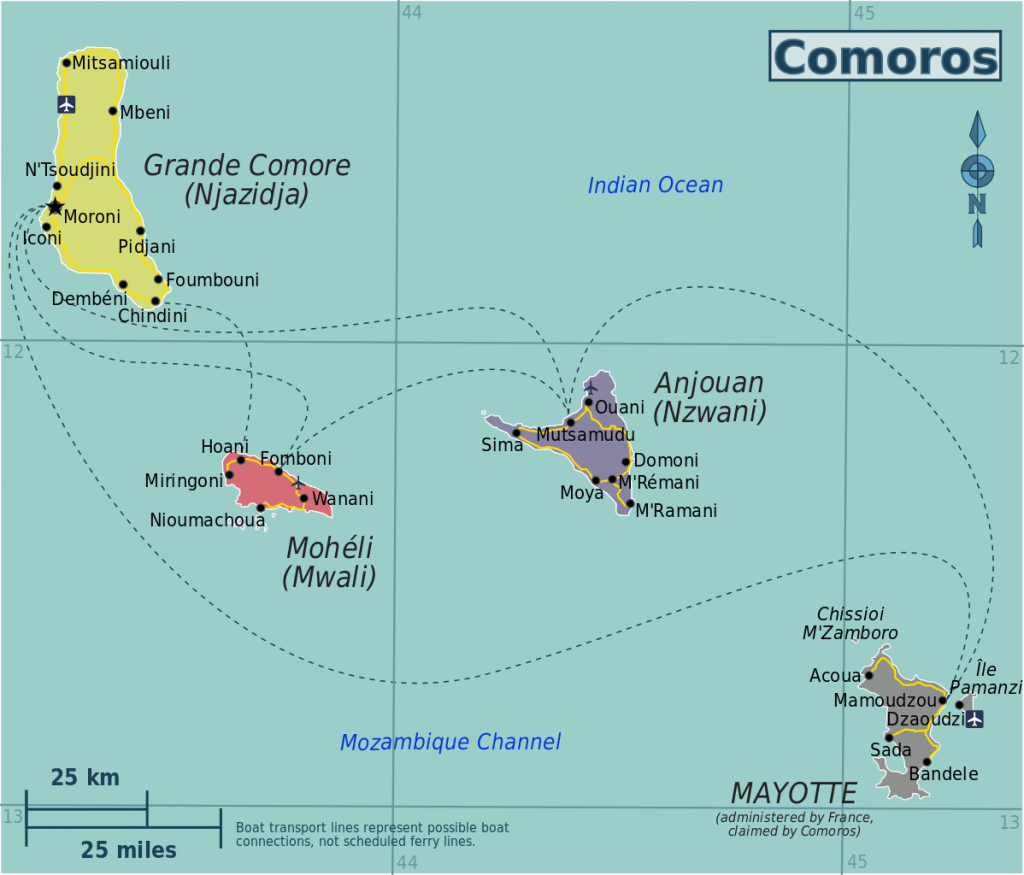

But the term 'irregular' is contentious in a place where more than half of adults were born elsewhere, and in which 95% of migrants hail from the nearby Comoro Islands. In this context, understanding Mayotte’s relationship with the Comoros is crucial. To gain this understanding, we must ask two key questions. Firstly, why do Comorians still consider Mayotte home, even after formal separation from the Archipelago? And secondly, how is this sentiment of belonging received and dealt with on the island and in the corridors of power in Paris?

During the colonial era, the French government nurtured, encouraged and mediated long-term migration patterns. The virtues of these patterns might provide us with some initial answers.

The island of Mayotte fell under French authority in 1841 but it was not joined by the Comorian archipelago until 1886. Back then, the archipelago was referred to as ‘Mayotte and dependencies’. The colonial power thus offered a privileged status to the island of Mayotte before things changed. For over a century afterwards, the entire Comoros Archipelago was administered as a single entity. During this time, the islands shared freedom of movement, ideas, language, cultures, and networks. As a result, native and migrant communities overlapped, and Mayotte remains a familiar destination for many Comorians.

Future migration governance must move on from mere border politics, to encompass identity, citizenship, legacies of inequality and colonialism

The French state's disregard for the consequences of this century of colonial mediation in shaping the modern history of the island, including the indigenous dispute it has cultivated, is evident. Indeed, tensions reached a high point in 1958, when the colonial administration transferred the regional capital from Dzaoudzi, on Mayotte, to Moroni on Grande Comore. This controversial event alienated the communities of Mayotte. The island's elites moved out, and Mayotte fell under the symbolic domination of the Grande Comore inhabitants, Wangazidja.

To gain a broader comprehension of mobility, I believe that it is essential for future migration governance to move on from mere border politics. This newer understanding should encompass identity, citizenship, and legacies of inequality and colonialism.

In 1974, a referendum on the status of the Comoros took place. An overwhelming majority voted for independence in the three islands of Grande Comoros, Anjouin, and Moheli. On the island of Mayotte, by contrast, 60% voted to remain part of France.

However, the legality of the distinction remains contentious. On 14 December 1960, the UN passed a resolution entitled ‘declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and people’. This resolution asserted that independence must be achieved while respecting the principle of the inviolability of borders inherited from colonisation. Comoros has consistently claimed Mayotte's return to its fold. In response, in 1995 the French government initiated the requirement of visas for individuals from the Comoros who wished to travel to Mayotte. This marked the end of freedom of movement across the archipelago.

France's recent deportations have sparked tensions. Comorian authorities assert that Comorians are 'home' in Mayotte.

Today, Many Mahorans support the French government. In the last presidential election, 43% (and nearly 60% in the second round) voted for far-right Marine Le Pen, known for her acute anti-immigrant rhetoric. This makes it easy for the French government to justify the displacement of ‘irregular’ migrants as a 'demand of the population'.

In the last presidential election, a majority of Mahorans voted for the far-right Marine Le Pen, known for her anti-immigrant rhetoric

This lack of consideration for the root causes of Mahoran resentment allows France to disregard the postcolonial dimensions of the dispute. Despite fragile social cohesion, Mahorans and Comorians share similar cultural and religious features. Migration has transformed the Archipelago over the years, leading to cross-fertilisation of language, religion, and customs.

The Mayotte case is a very good example of how colonial planning has impacted on postcolonial border communities: the stigmatised 'other' and the natives share many similarities.

Decontextualising migration data to fuel anti-migrant narratives is counterproductive. Indeed, it may prove downright dangerous. Understanding the long-term trajectories and effects of migration, particularly in contexts of colonisation and decolonisation, is crucial for crafting effective policies. There are certainly better methods than coercion.

Decontextualising migration data to fuel anti-migrant narratives is counterproductive, and may prove downright dangerous

More productive would be to acknowledge responsibility and to work with communities of destination and origin to improve social cohesion and alleviate poverty. It is surely time to see the bigger picture and act for political good rather than political gain.

For all its complexities, one question remains at the heart of the immigration debate in France: is the country ready to confront the entrenchment of colonial governance in its political institutions? This would require a significant re-evaluation of the country's policies, narratives, and history.

Mayotte's situation is a microcosm of the broader issues surrounding migration, colonialism, and postcolonialism.

To address the challenges effectively, we need to move beyond simplistic categorisations and confront the legacy of colonisation in border politics. Only then can we work towards solutions that are just, compassionate, and conducive to the well-being of all people, regardless of their place of birth. This is not just about the island of Mayotte; it is about shaping a more inclusive, equitable world for everyone.

People have the right to self determination even when you don t like the outcome. So Mayotte has the right to be a part from comoro islands.