Luca Bernardi and Robert Johns explore whether clinical depression may have contributed to Brexit. The striking evidence of depression influencing political attitudes suggests that connections between the two should be more thoroughly explored, especially as they show the potential to breed political alienation

According to National Health Service (NHS) statistics, depression is the second most common medical condition in England – ahead of obesity and behind only high blood pressure. And this is only diagnosed depression. Public Health England estimates that just half of those presenting to their General Practitioners with depressive disorders have their symptoms recognised. Their scale means that depression and anxiety are part of British society.

Yet they are not often thought of as part of British politics, let alone included among likely influences over people’s voting decisions. This despite the fact that depression affects the way people perceive and interpret information, and the way they reach judgements that are central to electoral choice.

depression affects the way people perceive and interpret information, and the way they reach judgements that are central to electoral choice

Depression has a particular impact on reactions to change. Sufferers from depression are:

The upshot is ‘status quo bias.’ Since many electoral choices take the form of status quo vs. change, the potential relevance of depression is clear. Let’s take the 2016 Brexit referendum as a case in point.

Based on the characterisation above, those with depression would have taken a dim view of the change involved in leaving the EU, and been sceptical about any prospect of ‘taking back control’. They should have leaned strongly towards Remain.

However, there is an obvious objection to this. One aspect of depression is a general dissatisfaction with life that is often associated with voting for change. Happier people are more (small ‘c’) conservative and more likely to vote for incumbents – even if that happiness comes from success for the local college football team.

a general discontent was thought by some to drive 2016’s big jolts to the status quo: the election of Trump and the Brexit vote

Conversely, a general discontent was thought by some to drive 2016’s big jolts to the status quo: the election of Trump and the Brexit vote. An analysis of the same data source that we use below provides some support for this. While feelings about one’s financial situation mattered more, there is evidence that those least satisfied with their lives in general were most ready to support Leave.

If depression were just a case of grave unhappiness or dissatisfaction, then, we would expect sufferers to be Leavers rather than Remainers. But it is more than that. In more severe cases, the uncertainty, pessimism and helplessness are likely to override any effects of dissatisfaction. The point is not that the clinically depressed would be satisfied with the status quo (typically, they are not), rather that they are prone to see change as likely to be even worse.

To test our claim about depression and status quo bias in the EU referendum, we used data from the long-running Understanding Society study (a rare case of a survey asking about Brexit and mental health), which used three measures of mental health:

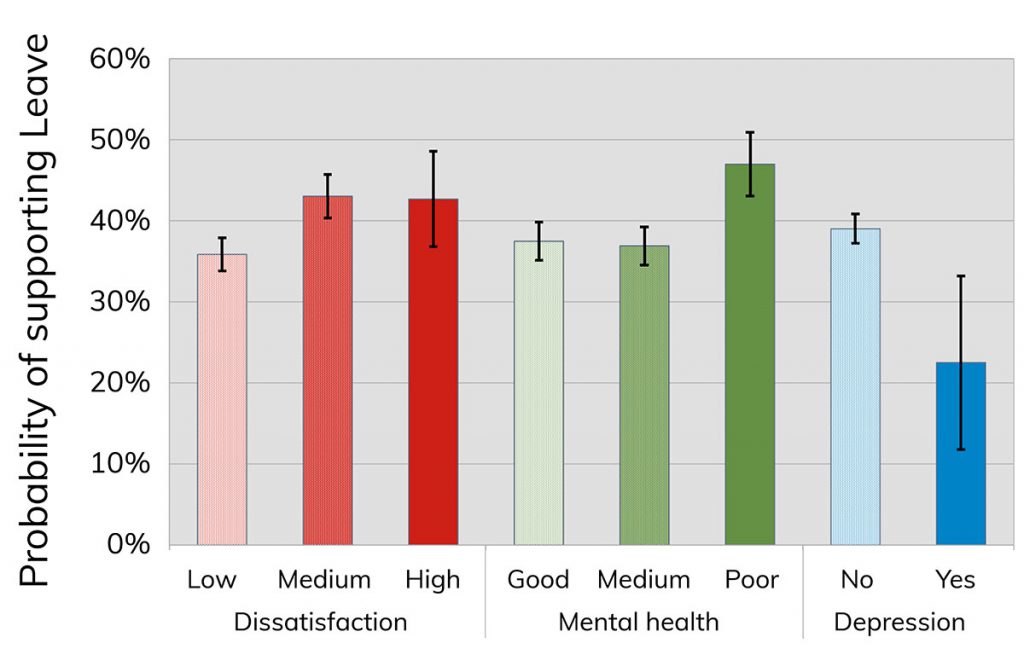

The graph below shows how pre-referendum support for Brexit related to these three measures. (The results come from regressions in which various background factors such as age, sex and social class are held constant.)

Consistent with previous research, those who were more dissatisfied with life were indeed more likely to support Leave. A similar pattern is observed with mental health. Those most likely to report feeling down or anxious were also least keen on the status quo. But when we move to depression, things are starkly different. Those diagnosed with clinical depression were a lot less likely to support the change option. There were not many such people in the survey – only just over 1% of our sample of around 12,000 respondents – and so the rightmost figure in the graph comes with a very wide 95% confidence interval (the black solid line). But the difference is large enough to be statistically significant. Clinical depression looks very different from a general dissatisfaction with one’s life or mental health.

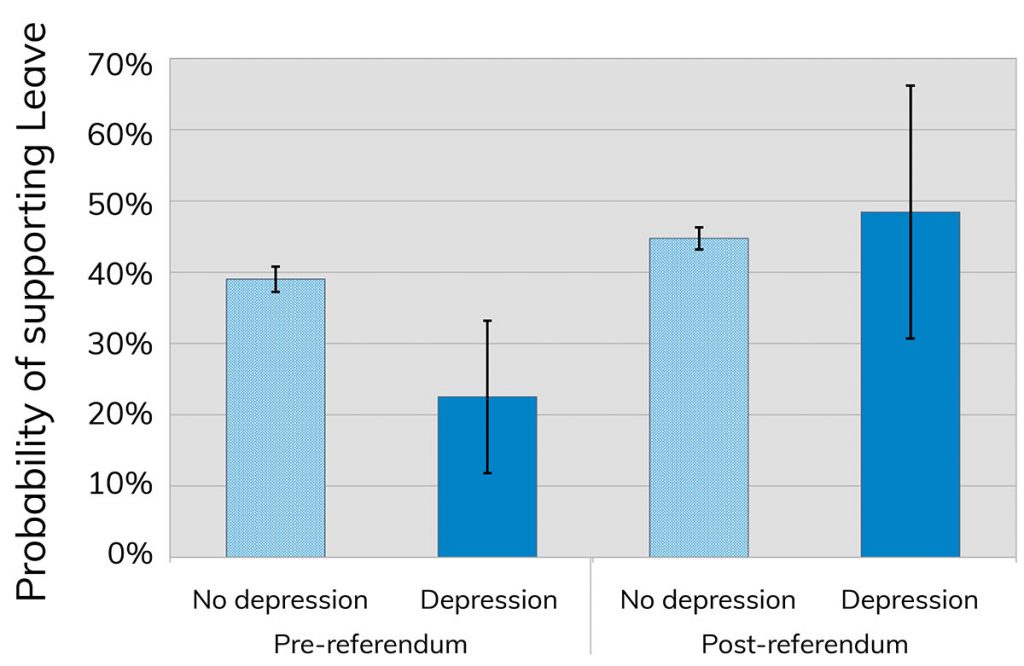

Can we be confident that this is about status quo bias, though? Maybe those with depression were just more concerned than others about Brexit’s implications for an NHS on which they rely? That is where the second graph comes in. It shows the same comparison between those with and without depression – but this time also among respondents surveyed after the referendum.

Strikingly, the gap closes completely. It looks as if the pre-referendum hostility to Brexit owed less to the substance of the issue and more to opposing the uncertainty and upheaval of change. The Leave vote shifted the psychological status quo; in turn, depression sufferers became less inclined to support a Remain option that had, by then, become the disruptive change.

The results here suggest a striking impact of depression on political attitudes. And this is just one of several possible connections between mental health and political attitudes and engagement.

we can envisage a vicious circle whereby those with depression form negative perceptions of politics, withdraw from politics, are less well represented, and end up still more alienated

Others are potentially more malign. For instance, we can envisage a vicious circle whereby those with depression form negative perceptions of politics, withdraw from politics, are less well represented in politics as a result, and end up still more alienated. And that is why exploring further the connections between depression and politics really matters.