To restrain profit-shifting by big corporations, Biden has proposed a global minimum corporate tax rate. This will have untold effects on economies such as Ireland's, which has depended on low corporate tax for economic growth, writes Anna Guildea

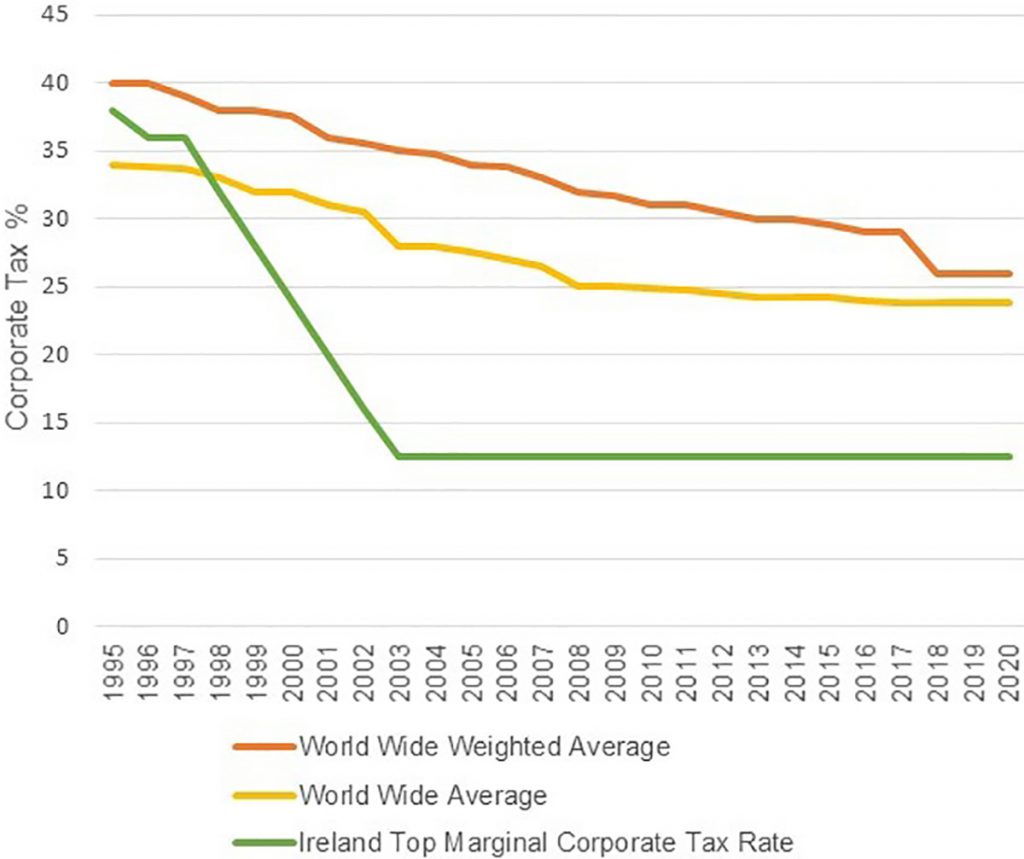

On 7 April the Biden administration announced plans to introduce a global minimum corporate tax rate. This could deter harmful profit-shifting practices by multinational corporations (MNCs).

For countries such as Ireland, however, low corporate tax rates have been a central pillar to economic growth. With its ludicrous tax concessions, Ireland has been irresistible to MNCs.

Biden’s plans could extinguish this appeal – leaving the Irish economy in uncharted territory.

One legacy of British occupation is that it left Ireland’s economy without any industrial base. On gaining independence, Ireland began attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) to develop its manufacturing sector.

Attracting FDI may seem common in contemporary economies. But in the 1960s, this strategy was unique to Ireland among European states that were, at the time, indifferent to the practice.

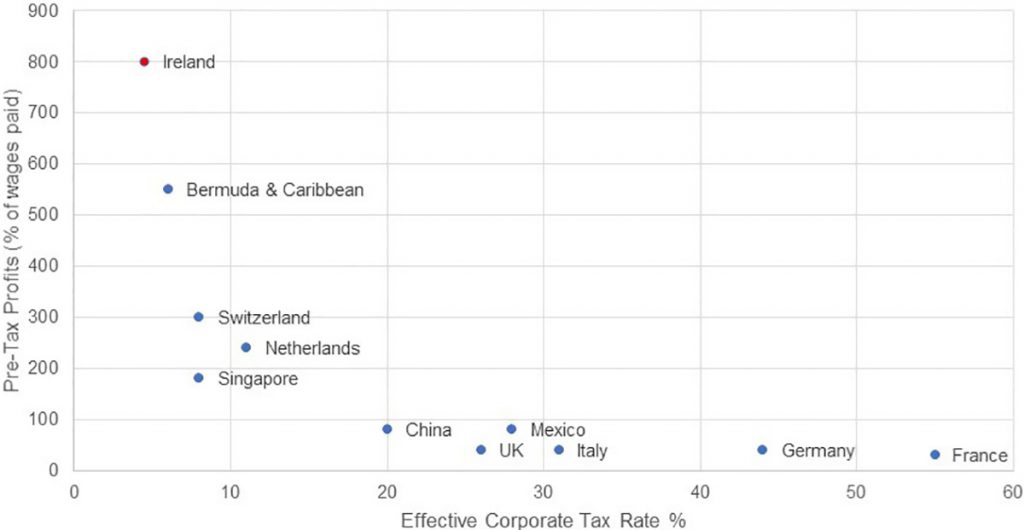

Today, this FDI manifests itself in ‘big-tech’ campuses across the country – including Google, Facebook and Apple. Investment originates overwhelmingly from the US. It has been crucial to making Ireland – in GDP terms, at least – one of Europe’s wealthiest countries.

British occupation left Ireland’s economy without any industrial base

Granting tax relief to corporations has been central to Ireland’s industrial strategy for decades. It has led the state to develop a deep ideology of regarding subservience to multinationals as a normal, neutral practice.

Deviating from this tax culture would constitute a profound shift in state praxis. It would mean departing from a near-religious mantra that only through tax concessions could Ireland provide jobs for its citizens.

The classic threat to any such deviation has been that investors would simply leave for alternative locations. Since Biden put forward his plans, many of Ireland’s most ardent tax policy defenders have changed their tune. They have assured the public that if tax levels rise, MNCs will remain to take advantage of the country’s infrastructure, highly skilled labour, and access to the single market.

These factors are considerable, legitimate claims to competitiveness. What’s curious, however, is that they were just as true when the Irish government fought the EU to refuse €13 billion in uncollected taxes from Apple. This was the most notorious of several incidences in which the state stood to profit but chose to maintain a non-negotiable stance on corporate taxation.

There was considerable innovation to Ireland’s industrial strategy in the 1960s. But today, the country’s growth model has become fixed to this role in facilitating tax avoidance for MNCs.

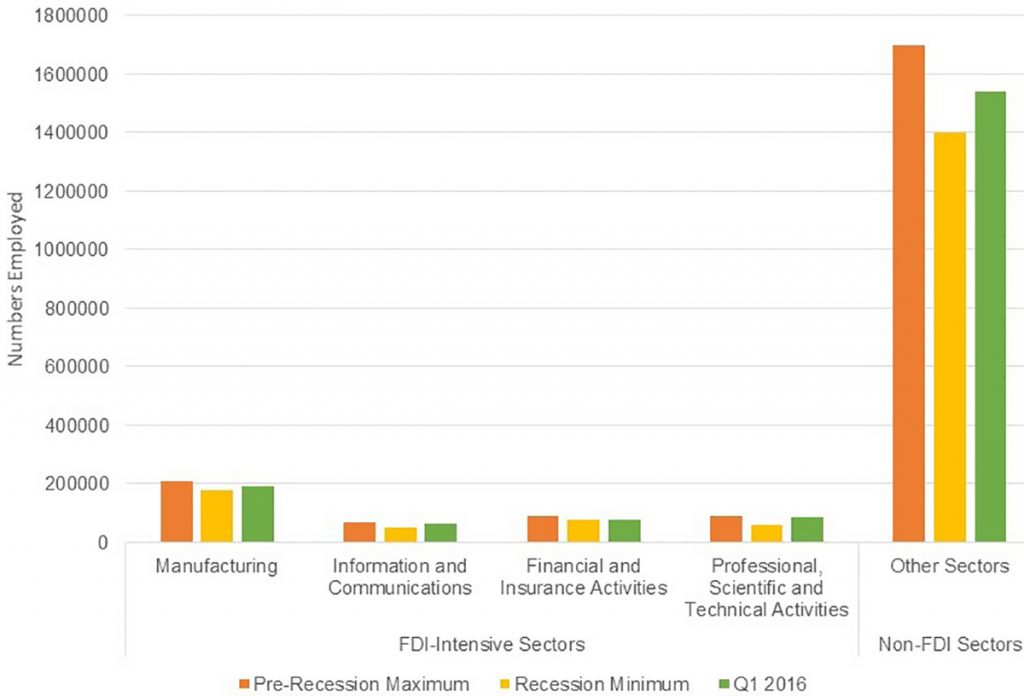

FDI certainly drives up GDP. But if it goes untaxed, no gains are made in the real economy to benefit the population's living standards. Most of Ireland’s post-2008 ‘recovery’ took place in FDI-heavy sectors, particularly Information Communication Technology. Any wage increases in the years following were essentially limited to FDI industries. Numbers employed by these FDI-intensive sectors pale in comparison with non-FDI industries, which experienced wage stagnation over the same period.

Following the Troika bailout, tax revenue in Ireland fell almost across the board. The exception was labour income tax, which increased every year from 2008 to 2016 – against a fall in average earnings.

If foreign direct investment goes untaxed, the real economy makes no gains to benefit the population's living standards

The Irish government did not consider increasing corporate income tax to alleviate the burden on the average citizen. Therefore, the working and middle classes – the majority of whom were employed in non-FDI sectors – paid the bulk of increased tax revenues during the austerity period.

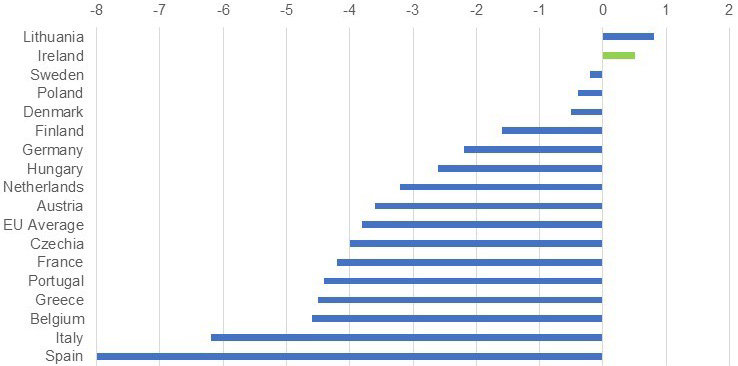

Accounting for FDI's distortion of Irish GDP puts a new slant on Ireland’s triumphant post-2008 ‘recovery’. Indeed, the current impression of Ireland being among the EU's wealthiest members becomes obscured.

Instead, we see a state with one of the worst rates of homelessness in the EU, the highest fees for third-level education, the most expensive childcare, one of Europe's least efficient insurance-based healthcare models, and a housing market in ruins.

In an ironic fashion, Ireland’s impression of strong economic ‘health’ in GDP terms means it will be among the ‘net contributors’ to the EU’s post-Covid recovery package.

The Irish finance minister has already alluded to a return to austerity if the country is to maintain high spending at the EU level. In circumstances reminiscent of those a decade ago, it appears that the role of Ireland in Europe's post-Covid recovery – a role forged by the state with its own tax policy – will be paid for by those who cannot avoid taxation.

Drawing further on the parallels, there is already talk of an 'economic bounceback'. So far in 2021, Ireland is the only EU economy to experience growth. This is likely thanks to GDP distortion attributable to the FDI-heavyweight pharmaceuticals sector.

The Irish finance minister has already alluded to a return to austerity if the country maintains high spending at EU level

Vaccine producers Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson, among other smaller firms, have Irish campuses. There they have historically reported disproportionately large profits compared to their subsidiaries elsewhere, which must pay higher rates of corporate tax.

The Irish public was infamously docile in accepting austerity measures post-2008. In previous recessions, Ireland resorted to its age-old solution to high unemployment: pushing its youth into emigration. But the nature of the pandemic means the country can no longer rely on essentially exporting its most politically active groups. Ireland's younger generations have consistently stood to lose the most from its economic mishandlings.

Furthermore, if Biden’s tax plans go ahead, Ireland won’t be able to depend on FDI to inflate GDP and cling to a rhetoric of ‘recovery’, as it did post-2008.

Following violent anti-lockdown protests, Ireland, which has thus far evaded the allure of populism, may uncover a new side to itself – a side that might not be as accepting of the economic hardship to come.

A global minimum corporate tax rate may reveal that Ireland’s tax policy, ardently defended for so long, has served multinational corporations far better than it has ever served its citizens.

Wise leaders understand that every decision has consequences, and the proposed global minimum corporate tax rate is no exception. While it may create more uniformity and fairness in the global economy, it could also have unintended effects on smaller countries like Ireland, which have built their economic models around low corporate tax rates. The key to navigating this uncharted territory lies in careful planning, collaboration, and creativity. It is essential to explore alternative paths and find innovative solutions that ensure the continued prosperity and well-being of all individuals and communities affected. Ultimately, it is our collective responsibility to create a more sustainable and equitable global economic system that benefits everyone, not just a select few.

Thank you for this insightful analysis of the potential ramifications of the proposed global minimum corporate tax rate on Ireland's economic model. The article compellingly outlines how Ireland's longstanding low corporate tax strategy has been pivotal in attracting multinational corporations (MNCs) and fostering economic growth.

Considering the implementation of a 15% global minimum tax rate for large MNCs, as agreed upon by Ireland and other OECD countries, how might this shift influence Ireland's ability to attract new foreign direct investment (FDI)? Are there alternative strategies or sectors Ireland could focus on to maintain its economic competitiveness in this new tax landscape?

Additionally, with the increasing emphasis on taxing profits where economic activities occur, how might Ireland adapt its fiscal policies to ensure continued revenue generation without solely relying on corporate tax incentives?

Understanding these potential adaptations would provide valuable insights into Ireland's economic resilience and strategic planning in response to global tax reforms.

Looking forward to your thoughts on these questions.