Chemical pollution is rising, and the global market share of European chemical industries is in decline. What can the EU do about it? Henry Hempel examines how the European Commission's announced revisions to EU chemicals regulation could combine economic incentives with chemical simplification

By May 2023, manufacturers and importers had registered over 26,000 individual substances under the EU’s central chemicals regulation, REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals). The increasing amount and complexity of substances and mixtures pose a risk to human health, the environment, and biodiversity.

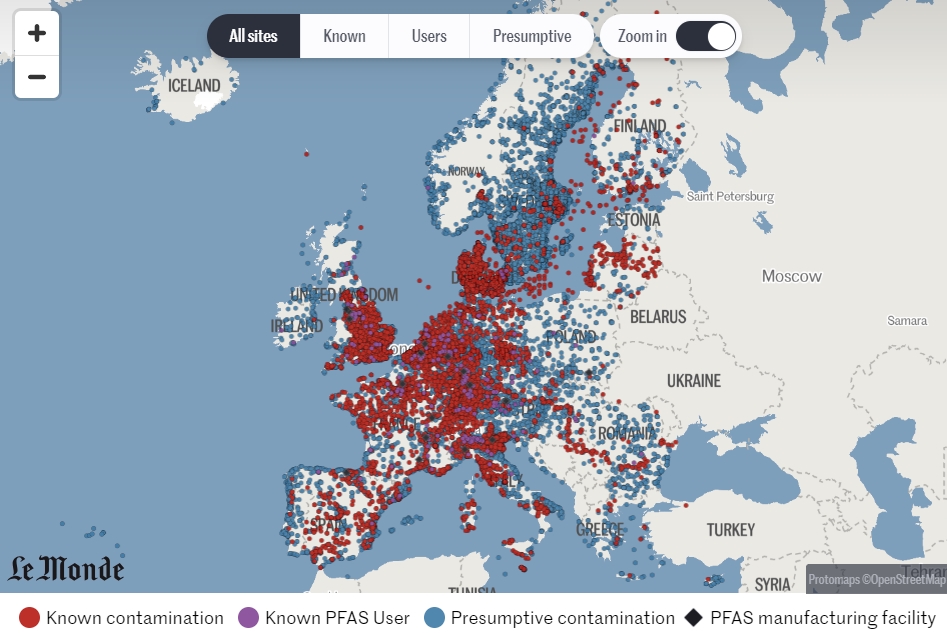

The European Environment Agency warns that the 'growing volume and diversity of chemicals' hinder effective hazard and risk management. The Forever Pollution Project, meanwhile, highlights how PFAS — man-made chemicals resistant to heat, water, oil, and grease — are widespread across Europe. PFAS, also known as 'forever chemicals', don't break down easily in the environment, and some are linked to poor health. Similarly, bisphenols, used for manufacturing plastics, are associated with non-communicable diseases.

(non-interactive screenshot; follow link in caption for interactive source)

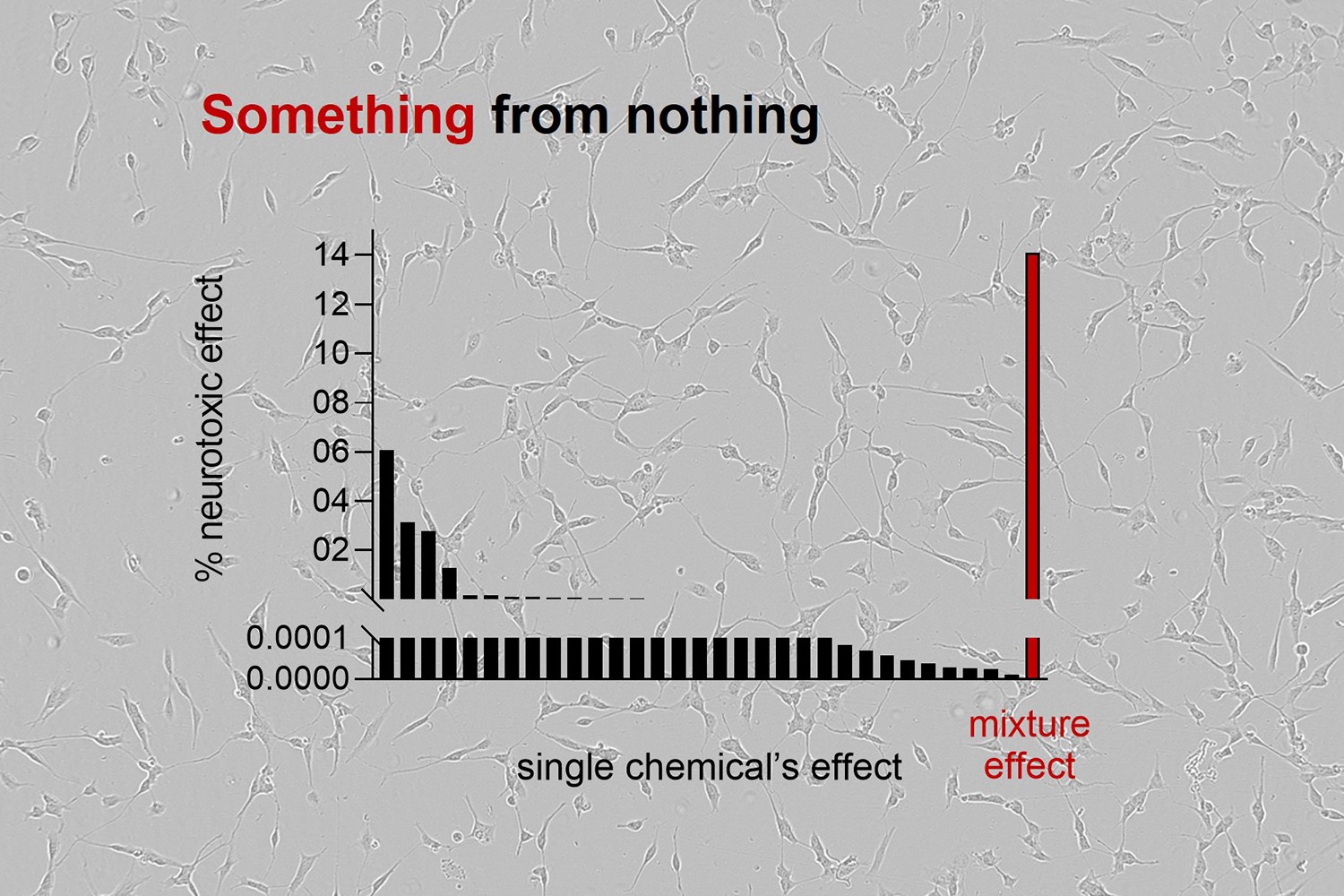

However, adverse effects are not posed by a single chemical or substance group alone. Chemical mixtures can harm the brain, nerves, or nervous system, even if individual chemicals would be considered inactive on their own — the 'something from nothing' effect.

(non-interactive screenshot; follow link in caption for interactive source)

The EU restricts some chemicals with adverse effects, such as bisphenols in food packaging. At the same time, some argue prohibiting substance groups — such as PFAS — without available or foreseeable alternatives risks weakening domestic industries.

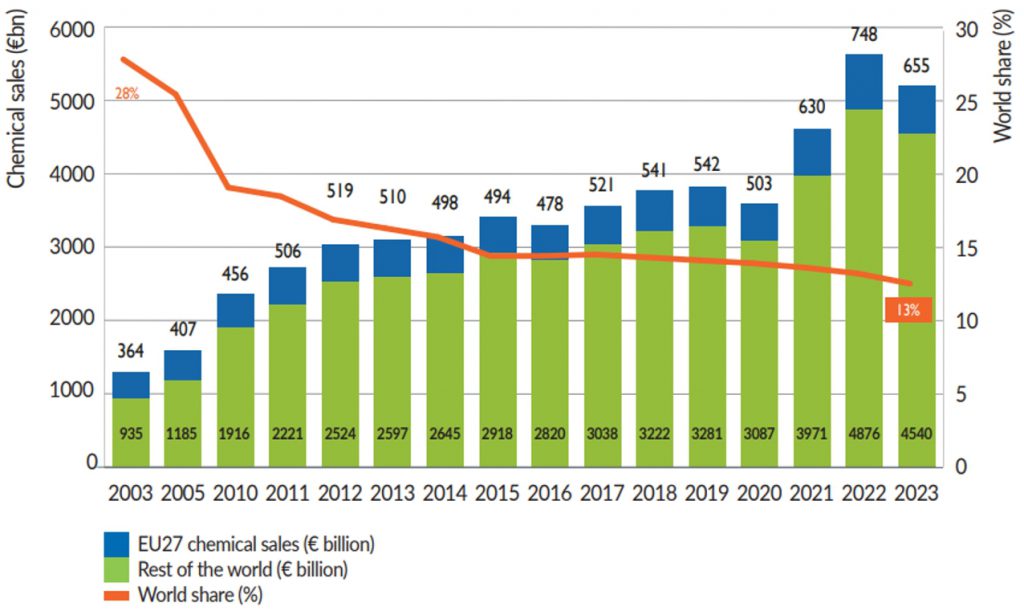

While environmental and health advocates highlight the dangers of chemical pollution, EU industry representatives warn of shrinking market shares in global competition.

The European Chemical Industry Council CEFIC notes: 'Over 20 years, the EU27 share of global chemical market dropped sharply.'

CEFIC cites increased competition from the USA and China, weak demand, rising energy costs, and stringent regulations as factors in this decline. It describes the EU’s industrial policies as complex and unpredictable. Other regions, it notes, have a more industry-friendly approach through incentives (USA) or through state planning and interventions (China).

According to its recently published Competitiveness Compass, the European Commission plans to propose a Chemicals Industry Package for the last quarter of 2025. The package will reaffirm the REACH revision postponed repeatedly under von der Leyen I.

EU chemical policy stakeholders hold different positions and expectations for the revision. Even the timing of the revision is contentious. German chemical industry association VCI opposes a rapid overhaul. It argues that 'no quick decisions on a revision are necessary', and favours changes to annexes or guidance documents over amendments to the legal text. Conversely, environmental NGOs criticised the postponement of the REACH revision during the von der Leyen I Commission. The NGO ClientEarth calls for 'urgent' revision, citing 'very high' non-compliance with REACH obligations. It also highlights new scientific findings, not recognised in current regulation, on chemicals' harmful effects.

Stakeholders are also contesting the scope of the revision. CEFIC stresses the need for regulatory simplification, efficiency and predictability to encourage investment. It calls for 'game-changer' policies to reduce 'unilateral burdens and isolated EU policy moves'. VCI emphasises that chemical diversity, availability, and safety are essential for industrial locations in Germany and Europe, as well as to meet sustainability targets.

Chemical industry stakeholders favour changes to annexes or appropriate guidance rather than legal amendments. Environmental groups, meanwhile, are demanding urgent revision of current regulation

In contrast, environmental advocates call for a REACH revision that prioritises health and ecosystem protection. Some are proposing chemical simplification: reducing the number and diversity of chemical mixtures in products. This, they argue, would lower exposure to harmful chemicals while creating new market opportunities.

Take baking parchment, for example. One production method involves adding a chemical to make the parchment grease repellent. Another creates grease-repelling characteristics by changing the way the paper is ground in the mill.

European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen, along with Commissioners Jessika Roswall (Environment) and Stéphane Séjourné (Industry) pledged to 'simplify REACH' by reducing administrative burdens for companies and streamlining legislative implementation. Similarly, Mario Draghi’s report on EU competitiveness, and the Antwerp declaration — signed by CEFIC and VCI — call for cutting red tape.

Industry advocates are calling for 'reducing regulatory burden' — but a focus on deregulation alone risks ignoring the urgent need to tackle chemical pollution

The EU is under pressure to reverse steadily declining market shares. Most goods manufactured in the EU contain chemicals. Chemical industries also represent 5–7% of the EU’s total industry turnover, and employ more than 1.2 million people. Many such industries produce products aimed at improving sustainability, such as electric vehicle batteries, and solar and wind technology.

Industry lobby organisations seem to focus on deregulation. However, simply reducing regulations on companies may fail to mitigate adverse effects on human health, the environment and biodiversity.

With the REACH revision proposal, the European Commission could, therefore, try to better connect pollution and competitiveness, instead of trying to solve them independently or treating them as conflicting interests. CEFIC mentions US policies as a good example of business friendliness through incentives. Perhaps the Commission could create incentives for initiatives that address pollution while enhancing EU competitiveness.

The European Commission could increase economic incentives for chemical simplfication efforts to better bridge pollution and competitiveness

This points, again, towards chemical simplification. In an era of PFAS and nanoplastics, chemical simplification offers market opportunities. Indeed, some large brands and consumers demand materials and products that are chemically simpler and safer to recycle. Putting these ideas into practice, however, requires significant innovation in science and engineering, and new design principles. The EU could therefore use the REACH revision to create incentives — such as tax cuts, dedicated funding, and subsidies — for companies that invest in or intend to increase their efforts in these directions. Continuous monitoring would ensure that such initiatives do not simply result in greenwashing.

Linking economic incentives to chemical simplification efforts is one way the European Commission could reduce chemical pollution and enhance competitiveness, while attempting to keep bureaucracy manageable.

This blog effectively explores the balance between EU chemical policies, pollution control, and economic competitiveness. A thoughtful analysis that highlights the challenges and importance of sustainable yet growth-oriented regulations.

Henry Hempel's analysis offers a timely perspective on the EU's complex task of balancing chemical safety with industrial competitiveness. As the EU revises its REACH regulations, it's crucial to consider both environmental protection and the economic vitality of its chemical industry. The article underscores the need for policies that safeguard public health without compromising the sector's global standing