Party competition sometimes resembles an auction, where parties seek to ‘buy’ elections through spending promises. Rory Costello argues that this is particularly likely to occur when parties are ideologically indistinct. Parties that do not expect to be in government are also more likely to over-promise

In an ideal world, an election manifesto would set out a political party’s honest intentions about what it would do if it was in government. However, parties will always be tempted to over-promise to win votes, particularly when it comes to spending commitments. After all, voters generally prefer more government spending to less, as the trade-offs involved (such as higher taxes or higher debt) are not always apparent. In extreme cases, elections can descend into bidding wars. The winner of such elections tends to be the party that promises the most – a phenomenon I call ‘auction politics’.

There are many examples of this occurring, historically and in contemporary politics. A good example that illustrates some of the dynamics at play is the 1977 Irish general election. The main opposition party in that election was Fianna Fáil. It produced a manifesto that contained commitments for unprecedented increases in public spending alongside significant tax cuts. This forced their main rivals, Fine Gael, to respond by increasing their initially modest spending proposals. Fianna Fáil went on to win the election, but then had to try and follow through on their commitments. The result was a huge increase in the national debt, leading to a deep economic recession in Ireland throughout the 1980s.

One of the reasons why this particular election turned into an auction is that the two main parties were ideologically indistinguishable from one another. When ideological competition is absent, parties are more likely to compete with one another in terms of how much they are offering.

In the absence of ideological competition, parties compete with one another in terms of how much they are offering

In a recent article, I test this argument using data on spending commitments in election manifestos from 20 countries over several decades. In line with expectations, party manifestos tend to focus more on spending commitments when the party is ideologically indistinct and when ideological polarisation in the party system is low. While there are many downsides to party polarisation, party convergence is also problematic because it makes bidding wars more likely.

The Irish example also highlights another factor that helps explain the dynamics of auction politics. Fianna Fáil threw caution to the wind in its manifesto because its prospects of winning were slim. Had the party expected to be in government after the election, it would have written its manifesto with one eye on the subsequent election, when voters would evaluate the party’s record and punish it for broken promises.

Parties in a weak electoral position with little prospect of leading a government tend to promise more than parties that are ahead in the polls

Cross-national evidence shows that parties’ electoral prospects at the beginning of a campaign shape the level of spending commitments in their manifestos. Specifically, parties in a weak electoral position with little prospect of leading a government tend to promise more than parties that are ahead in the polls. One consequence of this is that when parties attain power unexpectedly (as Fianna Fáil did in 1977), they find themselves shackled with fiscally irresponsible election promises that they never thought they would have to implement.

Not all parties will respond to political circumstances in the same way. Parties traditionally on the right of the political spectrum might be reluctant to promise significant increases in public spending, even if it would be electorally advantageous to do so. Indeed, evidence suggests a sharp difference between parties on the left and the right in terms of how much their electoral standing influences their spending promises.

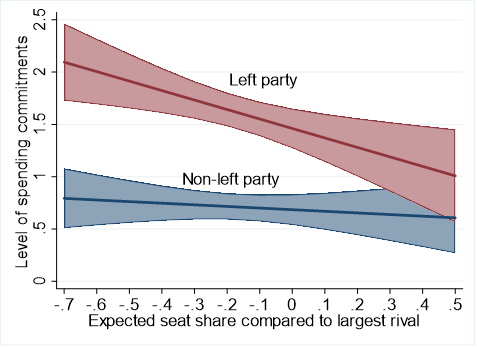

As the graph below shows, left-wing parties are very strongly influenced by how well they are polling at the beginning of the election campaign. Left-wing parties who are polling badly and thus have poor government prospects tend to offer the highest spending commitments. I measure this here as a ratio of expansionary manifesto statements to contractionary manifesto statements.

As left-wing parties’ electoral positions strengthen, the level of promised spending declines. However, we don't see the same pattern for other parties. It is possible that right-wing parties respond in different ways to their political circumstances. They might, for example, be less likely to promise tax cuts when they expect to be in government.

Political parties generally try to keep their election promises when they enter government. While this is of course desirable, we must also pay attention to the feasibility of those promises. Unchecked, parties may promise more than is prudent given the available resources, in pursuit of short-term electoral gains.

Parties may promise more than is prudent given the available resources, in pursuit of short-term electoral gains

The prospect of punishment in future elections does appear to serve as an important disincentive for parties to over-promise. However, this only applies to parties that expect to be in government. A degree of ideological competition can also prevent an election from descending into an auction. This is because voters will be reluctant to vote for a party to which they are opposed on ideological grounds, regardless of how much that party is offering. Beyond this, there is an important role for the media and independent agencies in scrutinising election manifestos to ensure that parties do not engage in auction politics.