The Ottawa Convention banning anti-personnel landmines is under serious challenge. In 2025, six state parties — Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, and Ukraine — began the procedure to withdraw from the convention. Henrique Garbino and Priscyll Anctil Avoine argue for a critical assessment of the rationale behind this decision, and its consequences

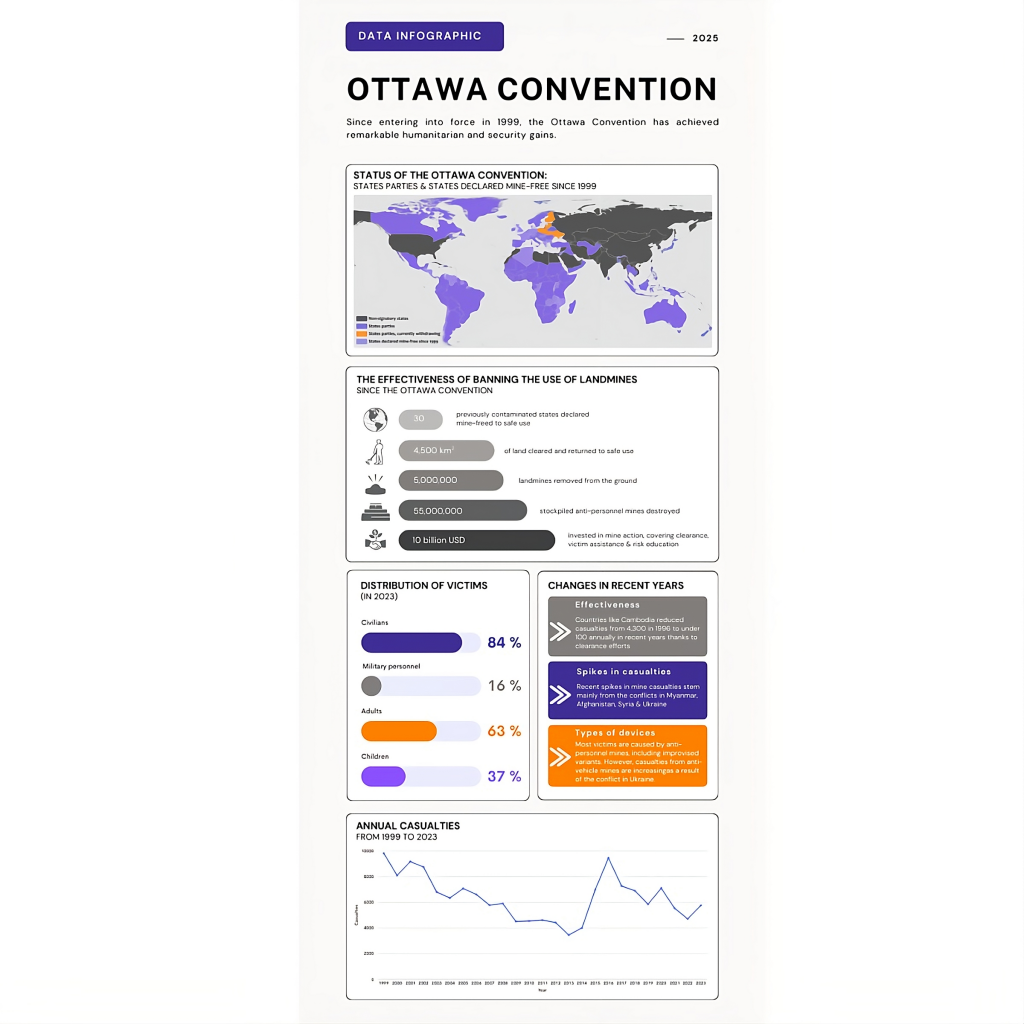

The 1997 Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction (Ottawa Convention or Ottawa Treaty) aims to eliminate anti-personnel mines (APMs). By August 2025, 166 states had ratified or acceded to the Treaty. Major powers and highly bellicose states, including United States, China, Russia, Israel, India, and Pakistan — which are also past and current manufacturers of landmines — are not parties to the Treaty. Despite this, it has still managed to achieve remarkable humanitarian and security gains.

The recent return of APMs into narratives of national defence, and the justification of their use in war, is alarming. State parties have pledged 'never under any circumstance' to employ them. But the prohibition of APMs is, above all, an ethical imperative.

We cannot yet know the consequences of withdrawing from the Ottawa Convention. But given that landmines can remain active for decades, the risks are evident and multifaceted. They also vastly outweigh any limited tactical advantages APMs may offer.

Landmines are the 'poor man's weapon' — in places such as Colombia, Sri Lanka, and Iraq, underdog insurgents use them to counter more powerful opponents.

Such factions also use anti-vehicle mines (not banned by the Ottawa Convention), intended to stop — or even destroy — armoured vehicles. Even conventional military forces use APMs mostly to stop enemy deminers from lifting anti-vehicle mines.

APMs fill only a narrow tactical purpose: as obstacles to infantry, in ambushes, or to protect infrastructure from saboteurs. Even then, legal alternatives such as command-wire 'claymore' mines exist that maximise damage to enemy forces and minimise APMs’ indiscriminate effects. The tactical rationale is therefore an unconvincing justification for withdrawing from the Convention.

In defensive military operations, landmines offer only marginal utility, creating a false sense of security that is exploitable by opponents

In conventional defensive military operations, landmines offer only marginal utility, while posing significant, long-lasting risks. First, mine-clearing equipment and combined arms can quickly breach or bypass minefields. They are effective only when observed and covered by fire. Yet even massive minefields failed to stop military offensive operations in, for example, Iraq (1991 and 2003) and Nagorno-Karabakh (2020 and 2023). Minefields often create a false sense of security, exploitable by opponents. In some contexts, unmanned border minefields also provide an infiltration route for smugglers and armed groups.

Second, people in policy circles often repeat that 'landmines cost only $1'. That figure, however, ignores costs related to the safe storing, transporting, laying, monitoring, maintaining, and eventually clearing of minefields, not to mention the healthcare costs to victims. Even underdogs, those who benefit most from APM use, are thus often reluctant to lay mines. If they do, they may well regret doing so.

Finally, anti-personnel landmines are notorious for causing friendly casualties. Moreover, insurgents have often lifted and redeployed mines, as they did in Vietnam and Korea. In 1942, Allied forces seized the largest minefield ever laid, the so-called Devil’s Gardens in Egypt, and succeeded in weaponising it against the Nazis.

The narrative of 'self-defence' as justification for retreating from the Ottawa Convention sets a dangerous precedent for the ethical and political commitment to preserving human lives in wars.

The humanitarian consequences of anti-personnel landmines are well documented. They cause death, injury, permanent disability, psychological trauma, social disruption, restricted access to land and essential services, and environmental degradation. So, if tactical utility is limited and costs are high, why do states persist in using APMs?

Justifying retreating from the Ottawa Convention as 'self-defence' sets a dangerous precedent: the humanitarian consequences of anti-personnel landmines include psychological trauma, permanent disability, and death

In states' current attempts to withdraw from the Treaty, arguments are vague and suggest closing the discussion to public scrutiny. The main reason appears to be signalling determination to 'do whatever it takes' to deter aggression. Deterrence requires not only the capacity and willingness to inflict harm, but also the readiness to endure harm. By this logic, landmines do indeed serve such a purpose, because those most affected are civilians living near minefields: often the state’s own population.

Furthermore, leaving the Ottawa Convention sets a dangerous precedent. The commitment to ban APMs is unconditional; it does not matter if the state party is at risk or not. Indeed, the Treaty itself states that if 'the withdrawing State Party is engaged in an armed conflict, the withdrawal shall not take effect before the end of the armed conflict'.

The Ottawa Convention's commitment to ban anti-personnel landmines is unconditional; it does not matter if the state party is at risk or not

Leaving the Convention on Cluster Munitions, as Lithuania did in 2025, seems to be the next step in the same direction. What follows, then, in the name of self-defence? Will states return to using chemical or biological weapons — or withdraw from the Geneva Convention altogether?

In January 2026, we convene a Swedish Defence University course on War’s Silent Legacy. The course will explore the multidimensional impacts of landmines. One of the first courses to tackle landmines' embodied, political, and environmental effects, it will examine the long-term and complex humanitarian outcomes of legitimising APMs.

It is time to reinforce global commitment to international law and arms control. While some observers are 'inspired' by the perceived 'usefulness' of APMs in the Russo-Ukrainian war, such weapons are only marginally effective in attritional, trench-based warfare. This is a form of conflict that few states are openly preparing to wage. These observers should also recognise the immense harm mines inflict on Ukraine’s civilian population, agriculture, and environment.

Now is precisely the time to uphold shared ethical and legal standards, to consolidate unity, and to resist efforts to erode them.