Populist rhetoric often pits a virtuous people against a corrupt elite. But when populist leaders invoke these definitions, do they always mean the same thing? Maurits Meijers, Robert A. Huber, and Andrej Zaslove explore the role of ideology in such definitions, shedding light on why populism remains a powerful political force

Populism revolves around a moral opposition. Populists claim to represent a virtuous, unified people betrayed by a corrupt, self-serving elite. These twin pillars — people-centrism and anti-elitism — lie at the core of populist ideology.

But who exactly are the people and the elite in populist parties’ eyes? Are these categories fixed, or shaped by ideology? How do populist parties differ from non-populists in how they define them? While existing studies offer anecdotal insights, we lack systematic, comparative evidence.

Our recent European Journal of Political Research article addresses this gap. Using data from the 2023 Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA), we explore how parties across Europe define the people and the elite. Our results offer one of the first large-scale assessments of how populism and ideology structure these concepts.

Following theorists like Ernesto Laclau, we understand ‘the people’ as an empty signifier — vague but politically potent. As Margaret Canovan noted, its ambiguity makes it versatile: it can mobilise class, ethnic, or national identities.

'The people' is an ambiguous concept; vague, but politially potent. It can mobilise class, ethnic, or national identities

Populists’ definition of ‘elite’ also varies, but usually means political officeholders. Depending on ideology, populist parties may target political, economic, media, or cultural elites, allowing them to frame themselves as outsiders against multiple power centres.

So, do left- and right-wing populists define the people and the elite differently? Are these definitions driven more by populism, or ideology? And how do they compare with non-populist parties?

There are two key influences on how a party defines the people and the elite: its degree of populism, and its ideological orientation.

Left-wing populists tend to frame the people in economic terms, as the working majority opposed to the super-rich. They often target economic elites such as multinational corporations or CEOs. Right-wing populists, by contrast, emphasise cultural belonging. They define the people in ethno-nationalist or nativist terms, and exclude immigrants or ethnic minorities. For them, the elite includes politicians but also cultural institutions like the media and academia, which they see as cosmopolitan and disconnected.

For left-wing populists, 'the people' means the working majority. Populists on the right define 'the people' in ethno-nationalist terms

Despite these differences, populists across the spectrum portray political elites as corrupt. Increasingly, left- and right-wing populists also criticise media elites, often accusing journalists of bias and misrepresentation.

To test these ideas, we use data from the 2023 POPPA expert survey, which covers 312 political parties in 31 European countries. Experts assessed each party’s level of populism, ideological orientation, and views on societal groups.

We focus on two dimensions to examine how parties define the people:

To analyse the elite, we look at four groups:

Our findings show clear patterns in how ideology and populism shape party definitions.

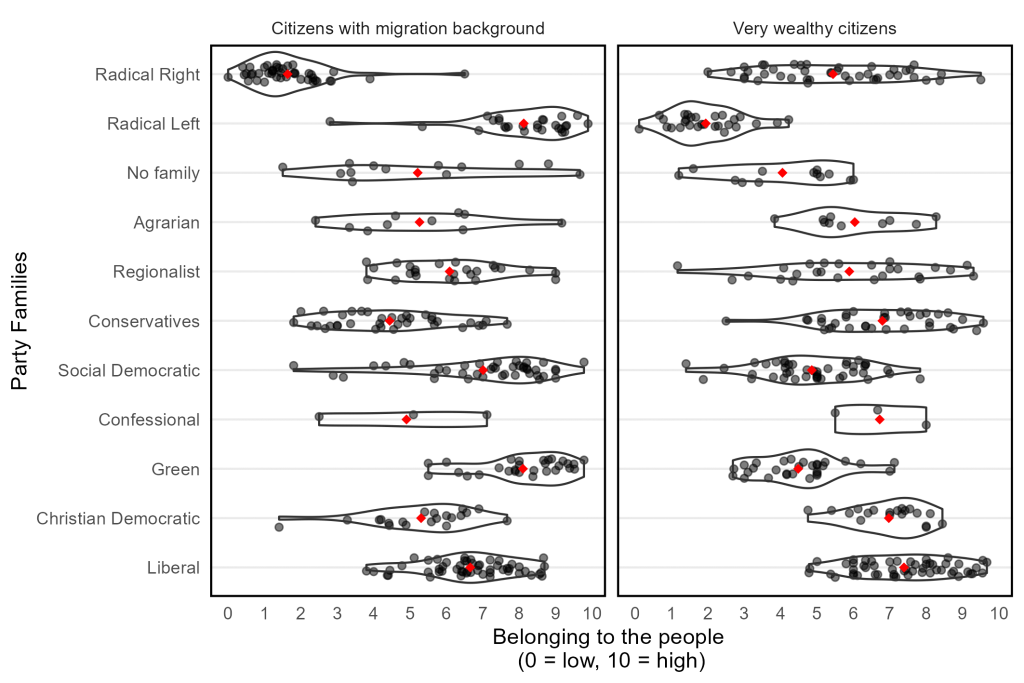

The graphs below show how parties position various groups, grouped by party families ordered from most to least populist. The first graph reveals clear contrasts in parties’ conceptions of the people: radical-right parties are more likely to exclude citizens with a migration background, reflecting a culturally exclusive view of the people. Radical-left parties are more inclusive toward migrants but tend to exclude the wealthy, emphasising economic criteria. Moderate parties show more balanced patterns — centre-left parties are culturally inclusive but less so economically; centre-right parties tend to do the reverse.

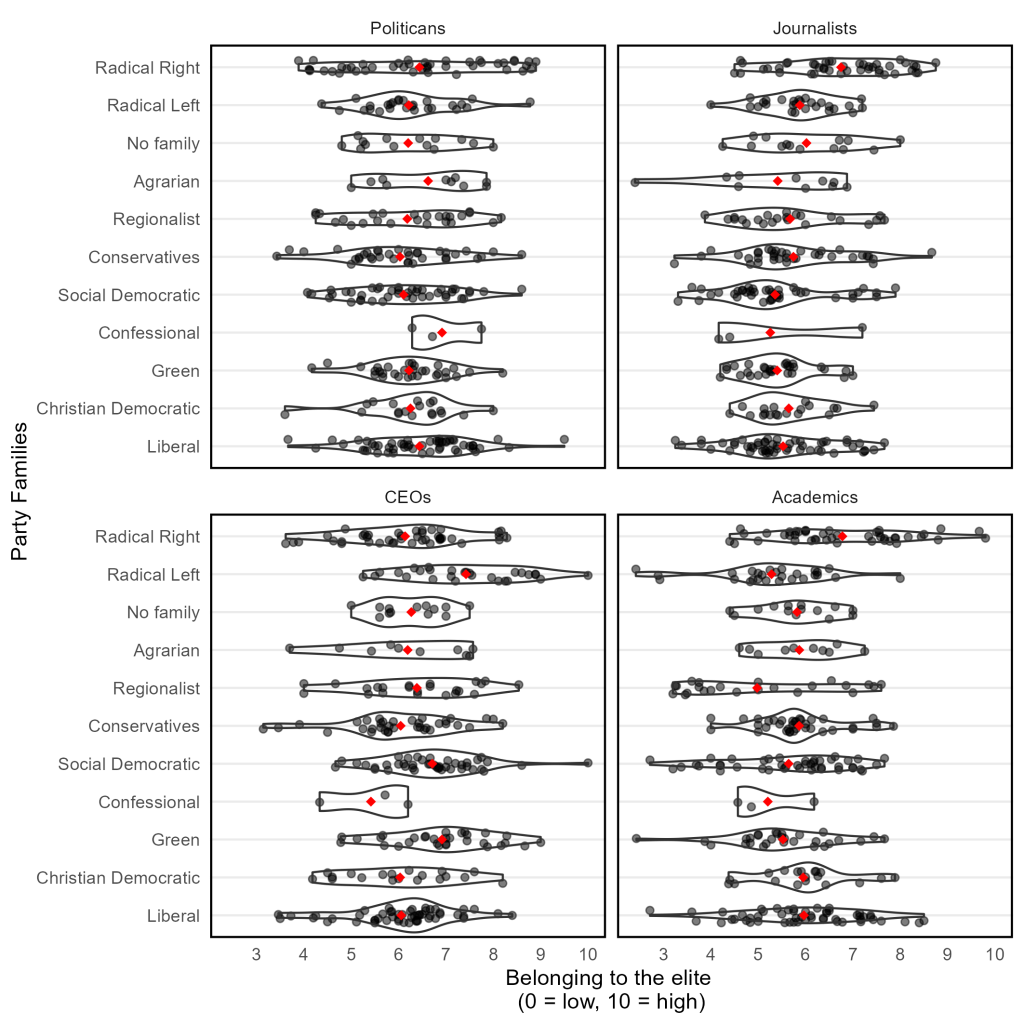

The second graph shows that populist parties are more likely to define a broad range of actors as elites. While nearly all parties see politicians as elites, populists — especially on the right — are particularly critical of journalists and academics. Left-wing populists are more likely to target CEOs. Mainstream parties show less consistent patterns, suggesting that anti-elite sentiment is more closely tied to populist rhetoric than to ideology alone.

To better understand what shapes how parties define the people and the elite, we ran regression analyses using data on parties’ ideology, nativism, and degree of populism. Treating populism as a continuous variable allows us to assess whether definitions are driven primarily by populism itself or by other ideological factors, such as left–right orientation, economic views, or nativism.

All three factors matter for defining the people. Nativist parties are more likely to exclude migrants, while economically left-wing parties tend to exclude the wealthy. Populism reinforces both dynamics: it amplifies cultural exclusion when combined with nativism, and economic exclusion when paired with left-wing ideology.

For the elite, populism is the strongest driver. Populist parties — especially on the right — are more likely to label journalists, academics, CEOs, and politicians as elites. Media elites are their most frequent target. Ideology and nativism, by contrast, play a much smaller role.

Our findings underscore populism’s ideological flexibility. Definitions of the people and the elite are constructed according to a party’s worldview. Populist parties tailor definitions to fit their core message, mobilising support against a range of perceived enemies.

Populist parties tailor definitions to fit their core message, mobilising support against a range of perceived enemies

At the same time, populist parties share a common logic — one that simplifies complex social landscapes into a binary moral struggle. Understanding how this logic works across the ideological spectrum helps us grasp why populism remains such a powerful and adaptable force in contemporary politics.

2018 and 2023 POPPA data is available for download. Explore interactive data on the POPPA website.