The EU has activated a Covid recovery package worth a staggering €672.5 billion. Observers tend to focus on the role of European capitals, intergovernmental institutions, and the European Commission's coordinating role in delivering it. Yet, argues Stefano Braghiroli, we shouldn't ignore the role of the European Parliament...

On 1 June 2021 the EU activated the most ambitious financial instrument in its history. To make sense of what some see as Europe’s Hamiltonian moment, we must examine the specific role of the European Parliament in making sure the €672.5 billion NextGenerationEU recovery plan delivers what it set out to achieve.

Back in the first pandemic wave of spring 2020, nobody could have predicted the launch of such a package. Faced with the multiple challenges of Covid-19, many European governments blamed Brussels and its institutions for letting them down. In so doing, they conveniently overlooked the fact that the EU is what its member states make of it. Unilateral measures and uncoordinated responses proved that national capitals were doing no better.

Brussels and the liberal democracies attracted blame from all sides. Meanwhile, authoritarian regimes – from China to Russia – engaged in a global PR campaign to market their response to the pandemic. The pandemic also offered a useful opportunity for such governments to promote their model of governance, free, as it apparently was, from ‘unnecessary’ red tape and checks and balances.

failing to deliver a clear-cut pandemic response poses a fundamental threat to the resilience and legitimacy of our democratic system

Yet public discontent with rampant demagogues continued to grow. This shows that failing to deliver clear-cut responses and policies doesn't apply only to health and socioeconomic aspects of government. It also poses a fundamental threat to the resilience and legitimacy of our democratic system.

Clearly then, the coronacrisis response is hugely important for European democracy and the legitimacy of governance. It makes no sense, therefore, to overlook the role of the EU's only directly elected and democratically legitimised supranational institution: the European Parliament.

The Parliament’s voice matters. Since passing the Lisbon Treaty, its power has grown substantially, and it has become more active in intergovernmental decision-making. Including NextGenerationEU in the multi-annual budget gave the EP the key power of consent, turning it into a key stakeholder in shaping the EU’s response.

Including NextGenerationEU in the multi-annual budget gave the EP the key power of consent, turning it into a key stakeholder in shaping the EU’s response

The EP initiated the first pan-European call for action in April 2020, with the approval of the joint motion for resolution on ‘EU coordinated action to combat the Covid-19 pandemic and its consequences’. Many of its ideas can now be found in NextGenerationEU. To highlight the internal dynamics involved in the EP’s first response, I analysed the votes held on 80 amendments to the resolution.

On 17 April, the motion was approved with 395 votes, or 57% of MEPs. The supporting grand coalition of conservatives, liberal democrats, and social democrats appeared very cohesive; only two affiliated MEPs voting against the text. The large majority of negative votes came from the eurosceptic right and left. Most of the Greens abstained.

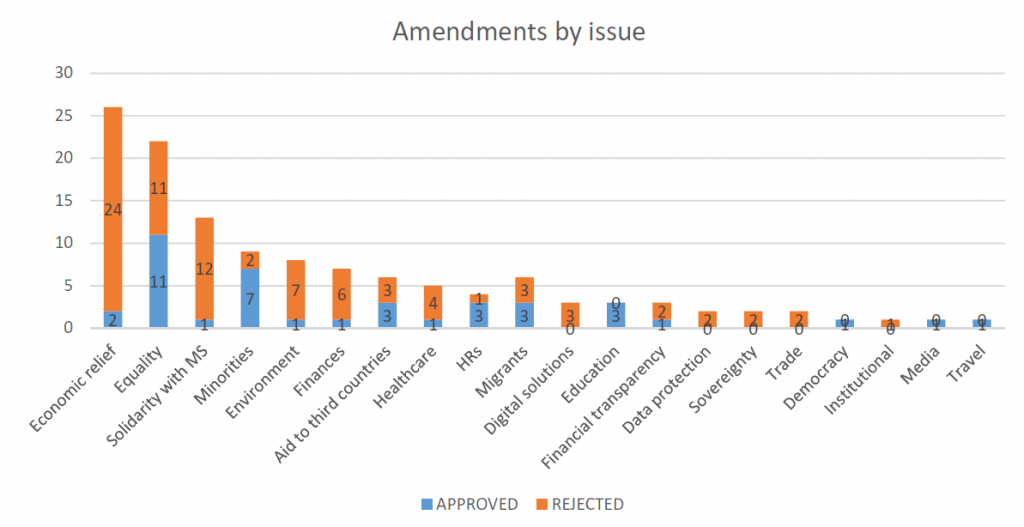

The majority of amendments addressed economic relief, solidarity, and aspects related to equality and non-discrimination. Surprisingly, only a few related directly to healthcare.

When it came to winners and losers, money seemed to make the difference. Proposed changes to the grand coalition’s text relating to economic measures, direct costs, or the use of financial resources, were almost ten times more likely to be rejected than votes not directly related to economic aspects of the crisis.

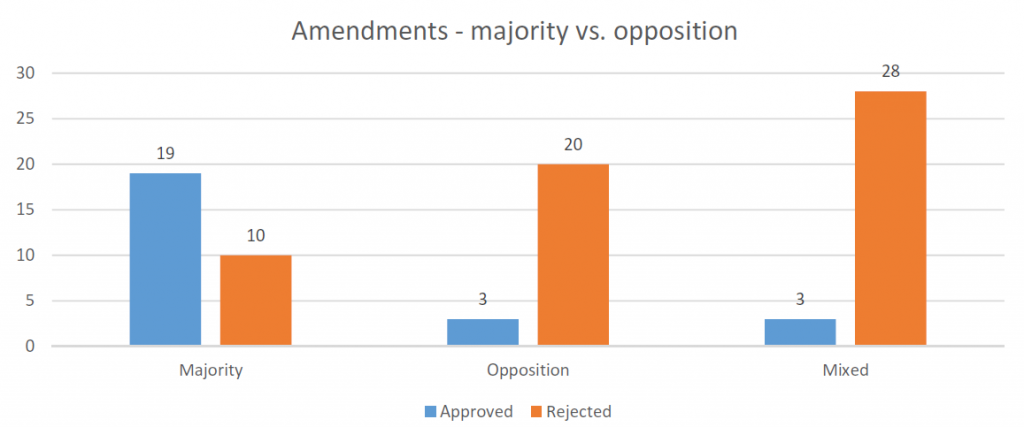

Given their stronger voice in the pre-legislative phase, grand coalition members also proposed fewer amendments, but with much greater success. If we compare their success rate with that of opposition MEPs, the contrast is striking: 66% vs 13%.

Across the 80 votes, the grand coalition also appeared remarkably cohesive. This stands in stark contrast with the Eurosceptic opposition, which was internally fragmented and divided along national lines. Ideology was a powerfully cohesive factor in the case of the radical left’s united front against 'neoliberal' aspects of the response.

Overall, when party groups were not cohesive, ‘national logic’ predominated. This reflects the split between maximalists, disappointed by an EU response perceived as weak, and pragmatists ready to support a ‘glass half full’.

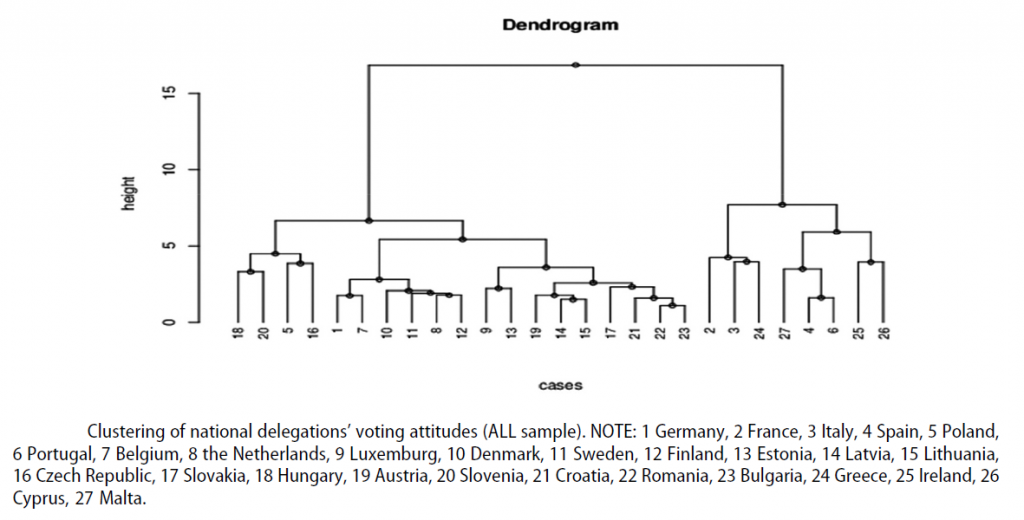

Analysis of voting coalitions along national lines reveals clusters. One consists of MEPs from 19 continental and northern European countries, the other from seven southern and Mediterranean countries.

Divisions appear to reflect the tensions between European solidarity and national interest of those countries less affected by the pandemic. Digging deeper, a ‘souvranist sub-cluster’ consisting of delegations from three Visegrad countries emerges. This is followed by two more centrist clusters of other continental and northern European delegations.

The nature of the votes strongly affected the coalition patterns. Again, it was a case of money matters. In non-economic votes, Germany joining the Southern group represented the most remarkable aspect. This group became de facto the central cluster. If we look only at economic votes, Germany and the South cluster could not be further apart. German MEPs are classified by the cluster analysis in the group that became known, during the intergovernmental negotiations on NextGenerationEU, as the frugal four.

A year on from the chaotic first wave, NextGenerationEU is a tangible reality. Despite the difficulties, the achievement of common action is likely to prove important to socioeconomic recovery. It's an achievement that also avoids the democratic ‘blackout’ many observers feared.

given the choice of overcoming the challenge together or going it alone and likely losing out, MEPs and national governments chose unity in action

Intergovernmental negotiations on NextGenerationEU, like those that followed on vaccine acquisition, mirrored the cleavages highlighted by the analysis of voting dynamics and coalition patterns in the EP.

When left with the choice of overcoming the challenge together or going it alone and likely losing out, MEPs and national governments chose unity in action. Still, that imperfect unity covers up persisting tensions between European solidarity on the one hand and national interest on the other; between the desire to preserve national sovereignty and the need for common European action.