Elections are the primary channel for political leaders to gain power in democracies. Amid concerns about the state of democracy around the world, Angelo Vito Panaro contends that in the 2024 elections, democratic regimes performed relatively well in comparison with autocracies

Democracy requires, at bare minimum, regular free, fair, and competitive elections. At its maximum, democracy involves procedural elements, such as the rule of law, political participation, and accountability, along with substantive elements, such as political rights and civil liberties. Assessing countries around the world on some key constitutive elements — political participation, alternation in government, and equal access to power — democracies performed relatively well in last year's elections.

2024 was the ‘super election year’. Voters headed to the polls in 92 countries, of which 21 held regional and local elections, and 71 presidential or parliamentary elections. Electoral data is available for 62 of these countries, of which 33 held presidential elections, and 52 parliamentary elections. Presidential and parliamentary elections took place in 23 countries.

Elections were held in 32 democracies and 30 electoral autocracies. The latter are regimes in which elections are neither free nor fair, and political competition is constrained. Examples include Russia, Iran, and Venezuela.

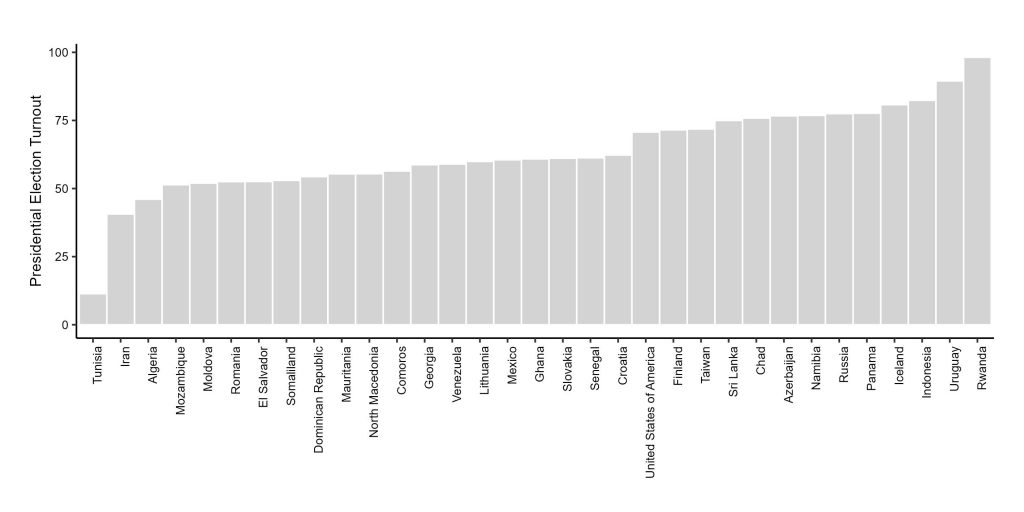

Voter turnout varied. Parliamentary elections have an average 64.7% turnout — higher than the 63.3% for presidential elections. Highest turnout for presidential elections was Rwanda, at 98.2%. Lowest was Tunisia, at 11.4%.

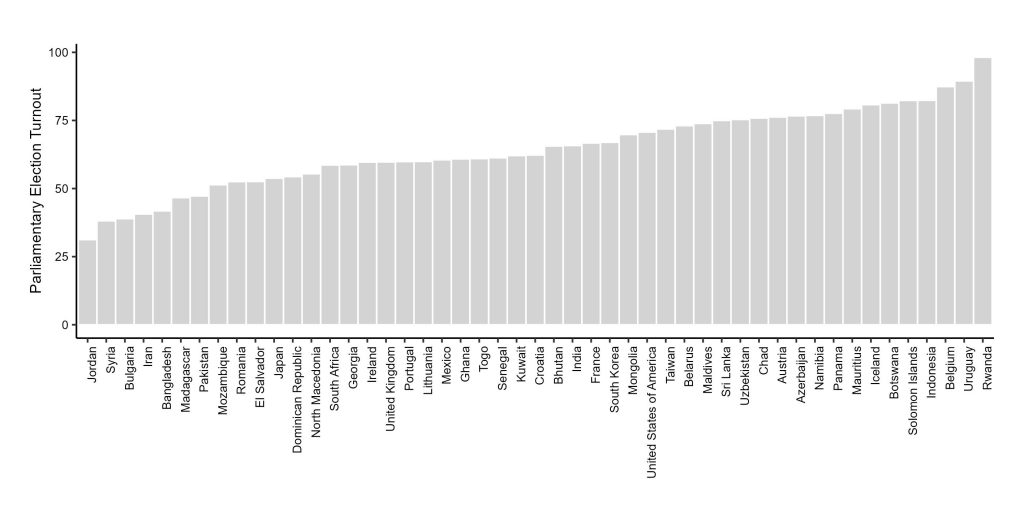

Parliamentary election turnout also varied. The highest recorded was Rwanda, at 98.2%. The lowest was Jordan, at 31.3%. Voter participation was higher in democracies, at 66.9% on average, compared with autocracies, at 61.4%.

In the 48 countries that held lower chamber or unicameral legislative elections (excluding Chad, from which no data is available), no turnover occurred in 26 countries. In these cases, the majority party or ruling coalition remained the same or largely unchanged. Only five countries experienced partial turnover. In these cases, minority parties, previously in opposition, assumed the leading position in the legislature, though remained dependent on other parties' support. In 17 countries, including Austria, Belgium, Indonesia, Portugal, and the United Kingdom, a new party or coalition gained the majority.

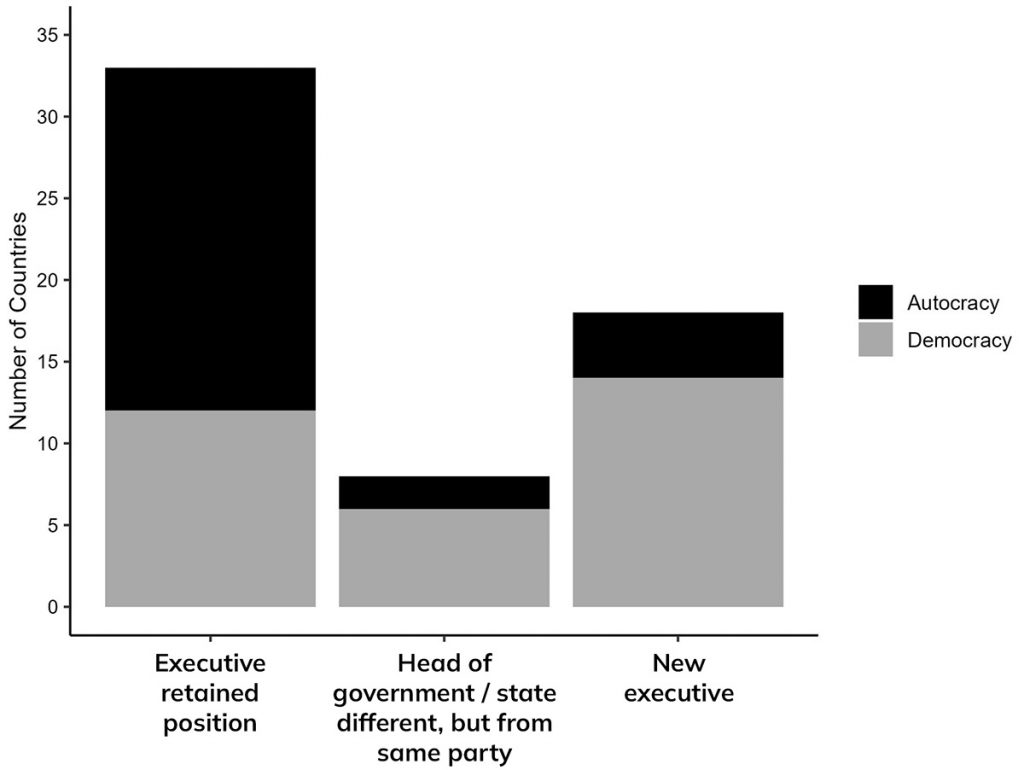

Interestingly, in 33 countries, the same executive remained in power. In eight countries, the head of state or government changed, yet still hailed from the same party or executive coalition that governed prior to the elections. Only in 18 countries, including Belgium, Portugal, Senegal, the United Kingdom, and the United States, did the newly elected president or head of government come from a different party or coalition to the incumbent.

Executive turnover was more common in democracies. A new party or coalition gained power in 14 democracies, while only four autocracies – Indonesia, Iran, Pakistan, and Somaliland – elected a new governing party or coalition. Executives were more likely in autocracies than democracies to retain power after the elections. Of the 33 countries where the same executive remained in power, 21 are classified as autocracies, and 12 democracies.

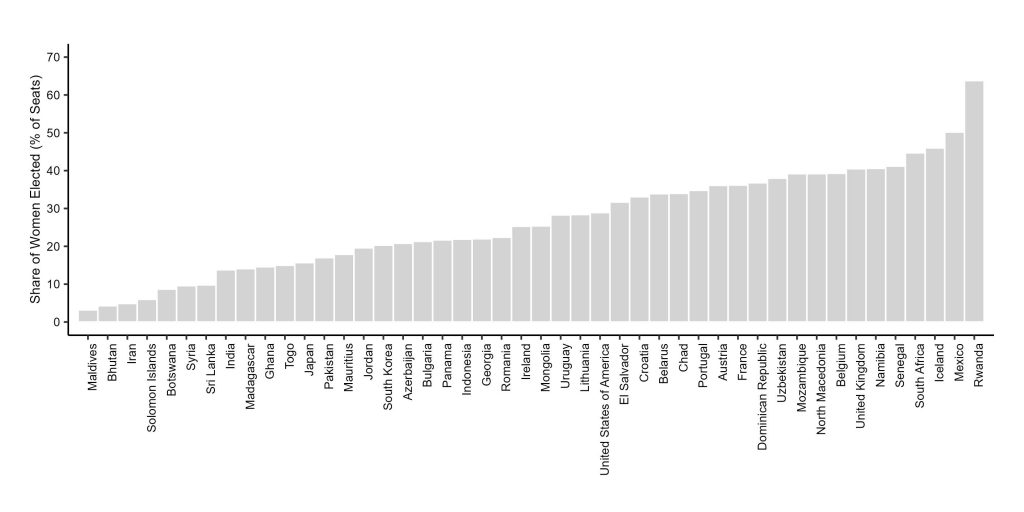

Only 23% of parliamentary seats across all countries were occupied by women. Proportions range from 63.8% in Rwanda to just 4.3% in Bhutan. Democracies allocated 28% of seats to women, compared with 18% in autocracies.

Reassuringly, the 2024 elections confirmed that voter turnout does indeed remain higher in democracies. A greater number of women were elected, and executive turnover was more frequent than in autocracies. Democracies continue to foster greater electoral participation and promote alternation of power. They also offer more opportunities than autocracies for women to attain political power.

Despite these findings, it is premature to draw optimistic conclusions about the state of democracy based on 2024 elections alone. Access to power for women remains alarmingly low, even in democracies. In Argentina, Austria, and the United States, anti-pluralist parties gained power, raising concerns about the future state of democracy in these countries. And even in countries like Poland and Portugal, where anti-pluralist parties failed to access government, electoral support for such parties increased. This trend, alongside the rise of far-right parties at the last EU elections, suggests that democracy may still have serious challenges to overcome.