Trump’s 2025 tariff shock marks a sharp turn toward a near-isolationist US trade policy. Yet given that US protectionism is expected to ease, Andreas Dür and Alessia Invernizzi argue that the international trading system is likely to weather the storm

In early 2025, the second Trump administration unleashed a rapid wave of tariffs – blanket duties, partner-specific 'reciprocal' rates, plus sectoral levies – that rattled markets and governments alike. Then came 'Liberation Day' on 2 April: a baseline 10% tariff on all imports, plus country-specific rates that could reach 50%. China retaliated quickly, and US-China tariffs soon reached levels not seen in modern times. Amid market turmoil, the administration paused many of the new tariffs to negotiate, but the overall direction remained clearly protectionist.

The scale is hard to overstate. One estimate suggests the US effective tariff rate had jumped from about 2.3% in 2024 to 16% by August 2025. This raises the question: is the postwar trading system breaking?

In recent research, we use a historical perspective as the starting point to answer this question. There’s a popular story in which the US was the reliable champion of open markets until very recently. But the record is messier. For long stretches, US trade policy has been an eclectic blend. Even during periods usually remembered as liberal, protectionist impulses never disappeared.

US trade policy has long been an eclectic blend. Even during supposedly liberal periods, protectionist impulses remained

In postwar trade negotiations, the US cut tariffs, yet domestic pressures for shielding sensitive sectors persisted. Later, major liberalisation efforts coexisted with the imposition of a surcharge under President Nixon and targeted restrictions in the 1980s. And even in the 'free trade' era after the Cold War, controversies like North American Free Trade Agreement ratification struggles and the 1999 Seattle protests revealed deep divisions.

In short, US trade policy has almost always combined liberal and protectionist elements, and the balance has shifted over time.

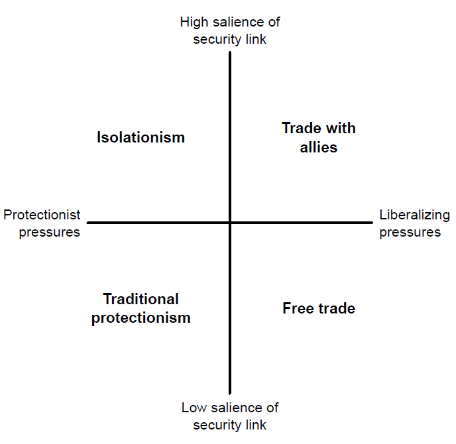

How does contemporary US trade policy fit this pattern? We suggest thinking in two dimensions. How strong are protectionist versus liberalising pressures at home? And how salient is the link between trade and national security? When protectionism and security framing are high, a country approaches an 'isolationist' ideal type: high import barriers, plus a willingness to use export controls, sanctions, and other tools of economic statecraft.

By that yardstick, the US in 2025 is edging toward isolationist territory. But the details matter. The protectionist turn is unmistakable – visible in the sharp rise of discriminatory import restrictions in 2025. The security linkage has risen too, especially in measures targeting rivals and in export restrictions. Yet security rationales still represent a minority of trade measures overall, and security-motivated export restrictions have actually declined since 2022 (a year marked by extensive Russia-related sanctions). In other words: today’s US trade policy is very protectionist, with a moderate security overlay.

In 2025, US trade policy is edging towards isolationist territory: very protectionist, with a moderate security overlay

That distinction is important because protectionist surges often burn hotter – and fade faster – than security-driven realignments. Indeed, we expect today’s maximalist protectionism to ease through three channels:

Together, these forces are likely to push US trade policy toward a more familiar pattern: still tough and selective, but less indiscriminate – more exemptions, more targeted industrial policy rather than across-the-board tariff walls. Recent US moves to reduce tariffs on imports from Brazil and Switzerland support this view.

The postwar trade regime evolved with a degree of flexibility precisely because governments understood that politics would sometimes override economics. Over decades, the system weathered big stress tests: the creation of the European Economic Community (which triggered fears among those left out), the protectionist turns of the 1970s and 1980s, the China shock and the long stall of the Doha Development Round, the shock of the 2008 financial and economic crisis.

The postwar trade regime evolved with a degree of flexibility precisely because governments understood that politics would sometimes override economics

More recently, when the US blocked the World Trade Organization's Appellate Body, other members did not simply shrug and walk away but built alternative arrangements among themselves. And the system has accommodated major tensions resulting from China’s state-driven model – often seen as conflicting with the spirit (and sometimes the letter) of the rules – without disintegrating.

Nevertheless, if US policy stayed isolationist for a long time, the consequences would be severe: redirected exports, new waves of protectionism elsewhere, and severe pain for smaller economies with less bargaining power. But the most plausible trajectory is not so dire. Because US protectionist pressure is likely to ease, we expect the broader regime to endure, even if US tariffs remain higher than before.

Many governments still justify their actions in WTO terms, pursue plurilateral workarounds, and keep the basic architecture standing while waiting out the turbulence. The trading system was never built on perfect compliance; it was built to survive political weather. Today’s storm is real, but reports of the system’s death are premature.