The ongoing polycrisis is forcing governments into a reactive short-termism. But to allay anxiety and uncertainty, democratic leaders should invest resources in developing positive ideas for a joint future. Governments failing to convey hope, argues Greta Groß, only risks inciting populist 'retrotopias'

Uncertainty about the future is inherent in political crises. In political psychology, the inability to cope with ambiguity – uncertainty intolerance – has been linked to feelings of anxiety.

Germany offers a good example of this connection. The country is currently facing a convergence of crises, including climate change, ongoing global conflicts, and rising inequality. As a result, people are experiencing heightened fear of war, social decline and societal fragmentation, among other worries. Amid the polycrisis, however, these fears do not exist in isolation, but amplify and merge into a concomitant crisis of anxiety about the future itself.

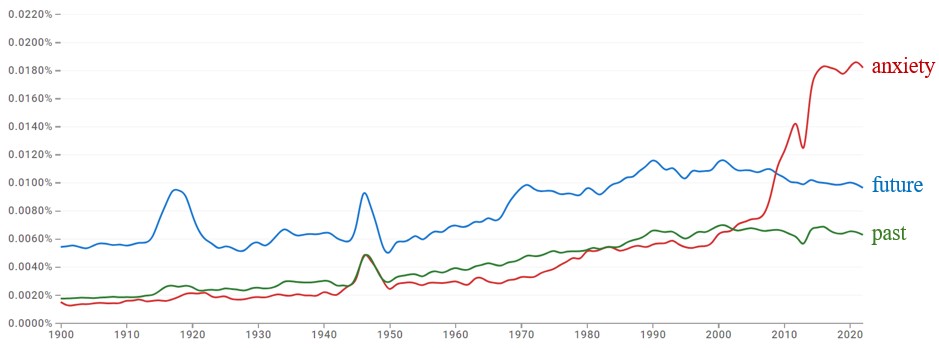

Anecdotal evidence from Google Ngram data reflects this connection between the future and anxiety in crisis times:

Google’s German text corpus reveals that in postwar Germany, for example, the term 'future' appeared frequently alongside 'anxiety', reflecting a cultural intertwining of these concepts. Notably, references to 'anxiety' surged dramatically following the 2008 global financial crisis. Some scholars identify precisely this point as 'the end of the end of history' and the beginning of the polycrisis.

In times of crisis, political leaders’ communication must go beyond technical problem solving, and should aim to alleviate those feelings of anxiety. As such, nostalgia has emerged in political communication, particularly among populist leaders. Slogans like 'Make America Great Again' reflect what Luca Versteegen describes as 'a longing for a traditional, culturally homogeneous societal past'. Nostalgic narratives calm people's anxiety about uncertain futures by offering a simplistic return to a supposedly better past. Such narratives have proven politically persuasive – especially among conservative voters.

Nostalgic narratives calm people's anxiety about uncertain futures by offering a simplistic return to a supposedly better past

This focus on the past is understandable. The more unpredictable the times, the more closely people cling to the familiar. However, nostalgia politics presents three major problems. First, it fails to address the reasons people may not want to return to the past. This could be societal inequality, discrimination on the basis of race or gender, or lack of opportunity. Second, many contemporary challenges, in particular the climate crisis with its non-negotiable timescales, make returning to the past impossible or undesirable. After all, industrial-era practices cannot rescue an overheating planet. Third, nostalgia-based narratives often depict a cultural homogeneity. This portrayal unites only individuals who fit within the boundaries of the imagined community.

Today's crises demand a forward-looking approach. However, findings from my work-in-progress paper, which analyses German parliamentary speech data 1990–2020 for narratives about the future, reveal an opposite trend. Following the global financial crisis – the period in which the term 'anxiety' surged in the Google NGram corpus – German politicians' use of future-oriented narratives declined dramatically. The correlation between a rise in references to anxiety and a decrease in narratives about the future remains anecdotal. But psychological literature suggests a deeper link: offering an optimistic roadmap towards the future can significantly increase social hope, and alleviate anxiety.

Despite this connection, the topic has received limited attention in political science research. This absence is partly justified, given that 'visions' are central to the persuasive toolboxes of charismatic fascist leaders. The dangers of such visions are well documented in studies on populism and authoritarianism, and there are numerous historical and contemporary examples. The historical baggage may explain why German politicians in particular are reluctant to express grand political visions. Yet, interdisciplinary research from psychology, management, and political philosophy highlights the transformative potential of shared positive visions. Such narratives reduce uncertainty, foster a sense of collective purpose, and fuel social change.

Shared positive visions can foster a sense of collective purpose and fuel social change

Political science itself is beginning to revisit the importance of positive narratives about the future for the health of democracy. Jonathan White argues that if citizens no longer believe in a better future, democracy suffers. This is why politicians must craft and communicate democratic visions distinctly different from the ideas promoted by populist and authoritarian figures. Optimistic narratives about the future, however, needn't rely on utopian promises or unrealistic goals. Instead, such narratives must be inclusive, rooted in present realities, and responsive to the diverse concerns of the broader population.

As climate change accelerates, inequality deepens, and geopolitical tensions persist, the stakes for democracies are higher than ever. In this context, stories of hope are not just tools for political communication – they are a democratic necessity.

Hopeful stories about the future are not just tools for political communication – they are a democratic necessity

And while my work-in-progress uncovers a decline in such stories in the German parliament after the global financial crisis to 2020, recent signals suggest a shift.

In early 2024, then-Chancellor Olaf Scholz acknowledged the importance of addressing public anxiety about the future. He argued that 'reducing uncertainties and developing something you can hope for' is crucial to countering the appeal of far-right populism. Scholz’s call for a vision that 'works for everyone' reflects an emerging understanding that offering positive visions of the future is not just desirable, but fundamental for democratic resilience.