Tackling violence against women requires targeted laws and robust policy infrastructure, an area in which the Brazilian government has been leading the way. Yet, as Victor Araújo and Malu Gatto argue, problems in implementation derive from conservative municipalities, which adopt fewer instruments to protect women from violence – with life-threatening implications

35% of women worldwide have been subjected to intimate-partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner. Every day in 2017, an average of 137 women worldwide were intentionally killed by a member of their family. The prevalence of intimate partner violence is particularly high in developing countries. In Brazil, a woman is subjected to violence every four minutes.

Unlike demands related to women's sexual and reproductive rights, combatting gender-based violence does not clash with conservative or religious values. Even conservative politicians such as far-right President Jair Bolsonaro publicly support policy to combat violence against women.

Even conservative politicians such as Bolsonaro publicly support policy to combat violence against women

The non-dogmatic nature of violence against women partly explains the rapid spread of targeted policies and legislation on domestic violence, which now exists in at least 155 countries.

Gender-based violence can have longstanding physical, psychological, and economic impacts on women, their children, and other family members. Governments must therefore combat gender-based violence with multifaceted policy responses.

To prevent revictimisation, experts recommend comprehensive policy frameworks. Women should have access to safe spaces and efficient protocols to register offences. They should have protection for them and their dependents, specialised medical and psychological support, and targeted judicial institutions. Public helplines, women's police stations, dedicated shelters, special courts, and legal representation are instruments that can bridge the 'implementation gap between law and practice.'

Brazil’s alarming rate of gender-based violence has made it a pioneer and policy innovator in this area. In 1985, São Paulo inaugurated the world's first Women's Police Station. In 2006, the country sanctioned Law 11.340, widely known as the Maria da Penha Law. This legislation recognises that gender-based violence has particular characteristics, and that combating it requires a framework of specialised protection and judicial instruments. Such instruments include Women's Police Stations, women's shelters, specialist courts, and wellbeing service centres.

Brazil’s alarming rate of gender-based violence has made it a pioneer and policy innovator

Brazil’s federalist structure, however, allows Brazilian municipalities substantial power over the adoption of policies and programmes. While the Maria da Penha Law applies nationally, the decision to adopt its recommended policy instruments has remained under the authority of municipalities.

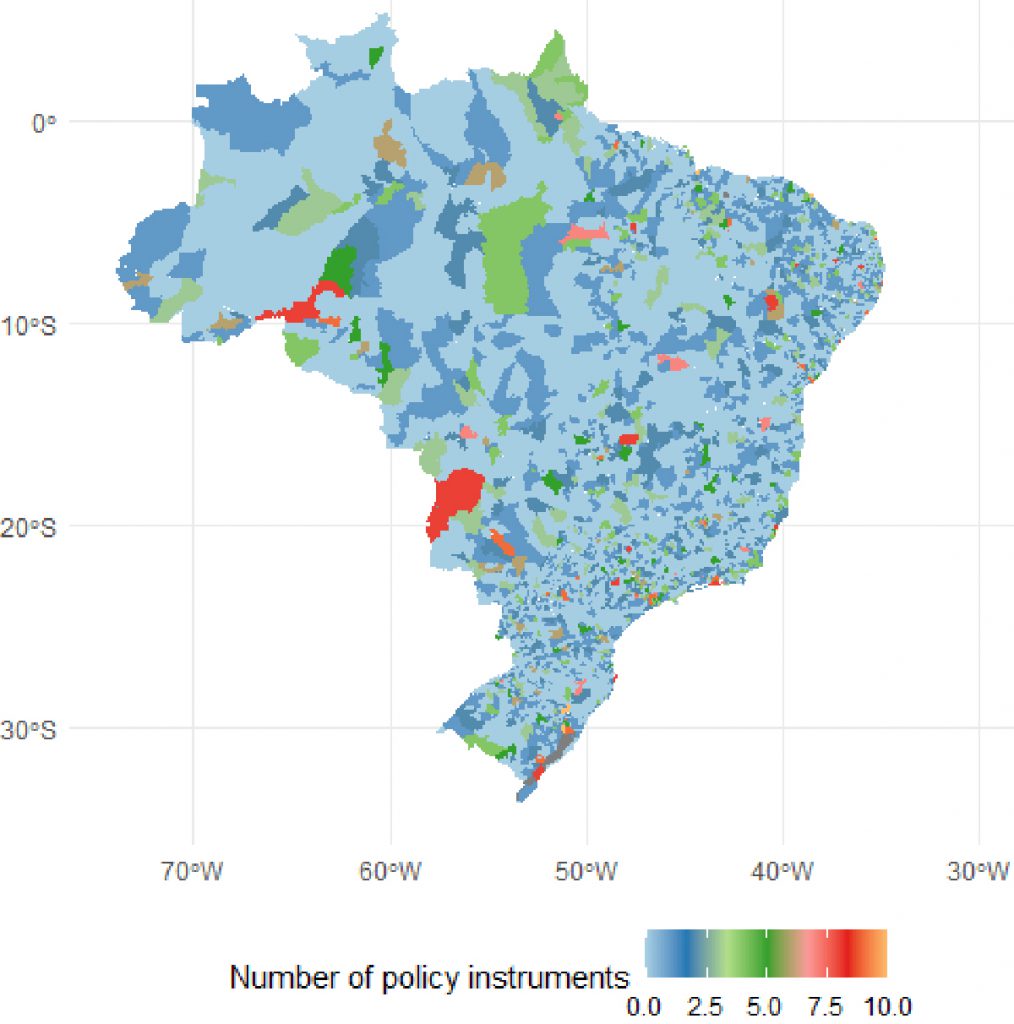

Fourteen years after the Maria da Penha Law came into force, only 21% (1,163) of Brazil’s 5,570 municipalities had adopted at least one of its recommended instruments:

At the core of liberal representative democracy is the understanding that voters’ preferences should translate into policies on the ground. Through free and fair elections, voters signal their policy priorities by selecting certain campaign platforms over others, and sanction incumbents who fail to act in their interests.

Normative values may compel conservative politicians into supporting (or, at least, not publicly opposing) legislation designed to protect women from violence. Legislation is a low-cost way to appease international pressures and women’s demands. But the implementation of on-the-ground policy infrastructure requires greater commitment and resource allocation that may conflict with conservative preferences.

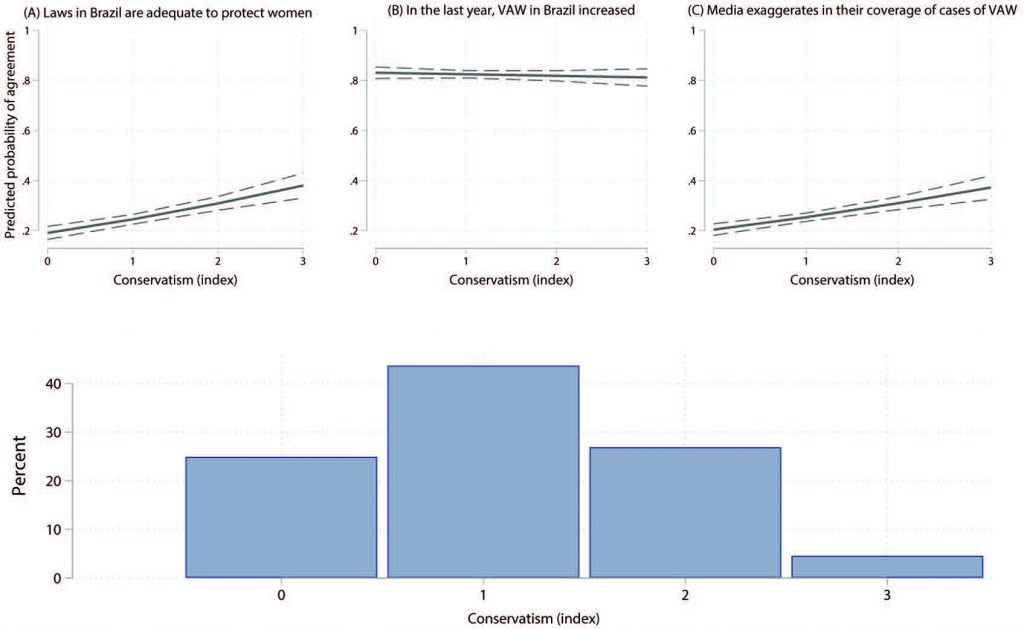

Conservative voters are more likely to believe that press coverage of gender-based violence is exaggerated – with on-the-ground implications

The figures below show data from a representative survey with Brazilian respondents. We find that conservative voters are more likely to deem existing laws sufficient to protect women. Conservative voters are also more likely to believe that press coverage of gender-based violence is exaggerated. This has on-the-ground implications.

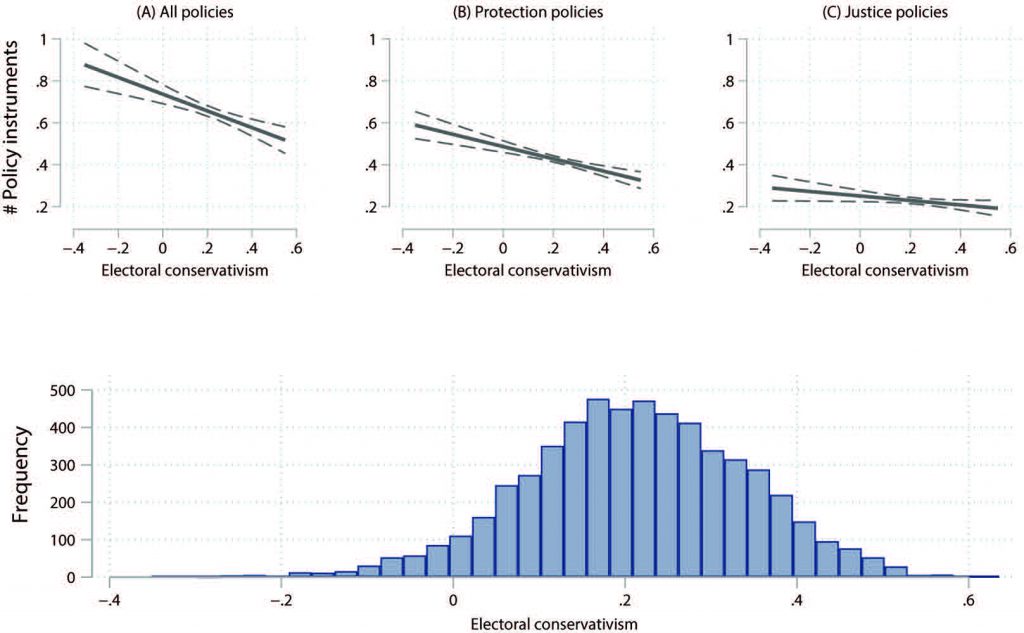

We combined data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics on the presence and number of policy instruments in each municipality with data on constituencies' 'electorally revealed conservatism' developed by Timothy Power and Rodrigo Rodrigues-Silveira in 2019. Below, we show that municipalities with conservative electorates are less prone to adopting policy instruments to combat gender-based violence. Municipalities with more conservative electorates adopt fewer policy instruments to tackle violence against women.

Conservative electorates are particularly detrimental to the adoption of protection policies. Such policies are key to ensuring the short-term safety of women and their dependents, as well as their long-term wellbeing.

Together, our results confirm previous studies showing that electorates' ideological preferences shape public policy on the ground. When electorates hold conservative preferences, however, policy congruence may incur a cost with regard to women's rights. The rise of conservatism and 'anti-gender ideology' movements around the world may translate into insufficient on-the-ground policy infrastructures to protect women — in spite of the global diffusion of laws to combat gender-based violence.